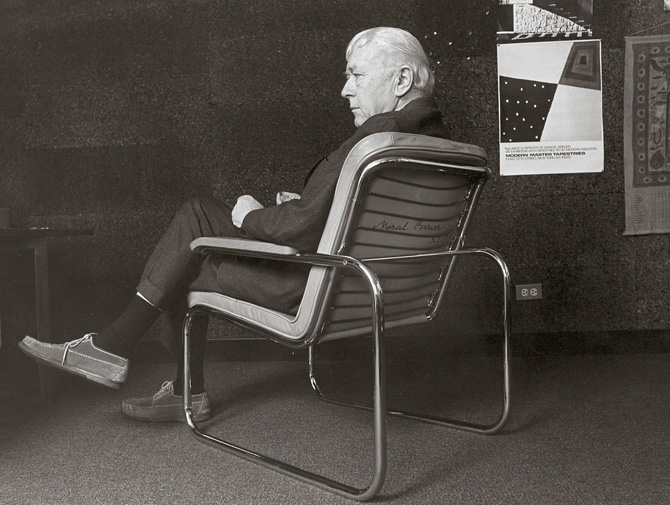

“At that time I was rather idealistic. 23 years old. I made friends with a young architect, and I bought my first bicycle. I learned to ride the bicycle and talked to this young fellow and told him that the bicycle seems to be a perfect production because it hasn’t changed in the last twenty, thirty years. It is still the original bicycle form. He said, ‘Did you ever see how they make those parts? How they bend those handlebars? You would be interested because they bend those steel tubes like macaroni.’ This somehow remained in my mind, and I started to think about steel tubes which are bent into frames—probably that is the material you could use for an elastic and transparent chair. Typically, I was very much engaged with the transparency of the form. That is how the first chair was made…I realized that the bending had to go further. It should only be bent with no points of welding on it so it could also be chromed in parts and put together. That is how the first Wassily was born.”

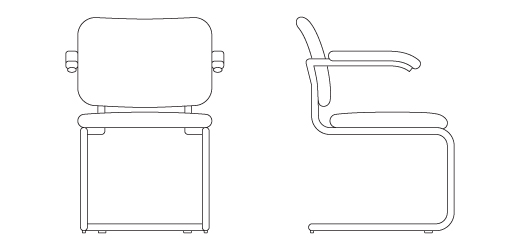

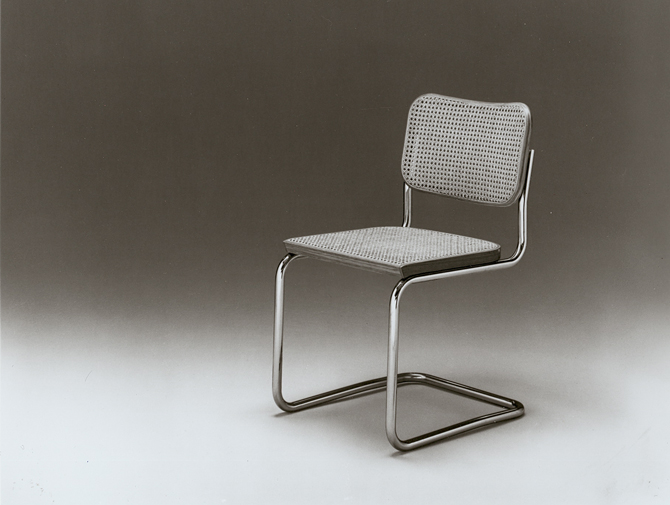

After completing the Wassily, Breuer felt that the potential grace of the material was not yet fully exploited. The Wassily design was very much influenced by the constructivist theories of the Dutch De Stjil movement. A familiar form — in this case the classic club chair — reduced to its elemental lines and planes. The result was an overlapping, dense arrangement of leather and tubing. For the Cesca chairs Breuer sought to better celebrate the new material. An attempt to reduce visual noise led him to the continuous line of steel supporting a cantilevered seat — one of the most copied concepts in 20th century furniture.