Colline Notre-Dame du Haut

A new exhibit features photographs from the Knoll Archives

From March 30 through November 1, Colline Notre-Dame du Haut will hosting an exhibit exploring the modern inspirations for Le Corbusier’s design of the chapel Notre-Dame du Haut. The collated materials featured in the exhibit bring together several photographs from the Knoll Archives, intended to highlight the chapel’s significance against the backdrop of twentieth century architectural design. Among other works, Eero Saarinen’s TWA Flight Center, commissioned in 1955 and completed in 1962, will be discussed as part of the exhibition. For details about the upcoming event, visit Colline Notre-Dame du Haut’s website.

Le Corbusier's Coline Notre-Dame du Haut, Ronchamp. Photograph by G. Vielle ©ADAGP, 2013.

Originally built in 1955, Colline Notre-Dame du Haut remains Le Corbusier’s only ecclesiastic building to date. Overlooking the provincial town of Ronchamp in eastern France, the chapel is recognized as the most atypical of Le Corbusier’s designs and often hailed as one of the first examples of postmodern architecture.

Himself a vocal proponent of rationalism in architecture, Le Corbusier founded the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) in 1928, which became a platform for the notable architect to disseminate his progressive, yet controversial ideas about “the functional city.” In the Athens Charter, CIAM outlined its utopic guidelines for urban projects, stating, "districts should occupy the best sites, and a minimum amount of solar exposure should be required in all dwellings. For hygienic reasons, buildings should not be built along transportation routes, and modern techniques should be used to construct high apartment building spaces widely apart, to free the soil for large green parks." Of many projects envisioned, the chapel remains one of only a few realized plans, reflecting the principles espoused in Corbusier's theoretical texts.

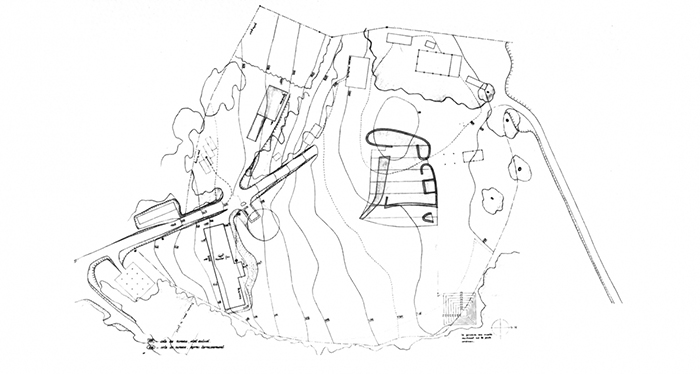

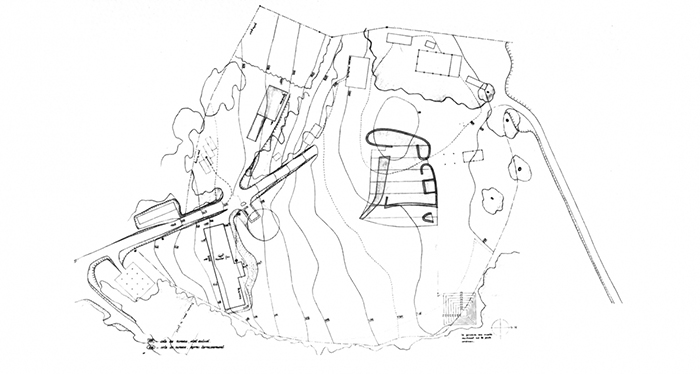

Le Corbusier's plan for Colline Notre-Dame du Haut, Ronchamp. Photograph ©RPBW, 2013.

A harmonious synthesis of materials—including concrete, stone, wood, cast iron, bronze, enamel and brass—the massive structure appears light and voluminous, throwing into relief the two most essential elements of architectural creation: light and matter. Sunlight bursts into the space of the chapel through a porous wall made up of sporadically sized stained-glass windows. Arranged along the clerestory, these punched-out windows take the place of traditional religious iconography and gilded spiritual objects designed since antiquity to refract candlelight throughout the room. Although denominational, the chapel is remarkably unadorned. A main alter and diminutive cross are the only vestiges of overt Christian motifs. Offering an explanation for the dearth of representation, Le Corbusier said of the design, “I wanted to create a place of silence, prayer, peace and inner joy.”

Interior and exterior view of the clerestory windows at Colline Notre-Dame du Haut, Ronchamp. Photograph by G. Vielle ©ADAGP, 2013.

Since the 1950s, several other modern designers have contributed to the surrounding architectural compound, including Jean Prouvé and Renzo Piano.

Jean Prouve's three-bell portico. Photograph by G. Vielle ©ADAGP, 2013.

Jean Prouvé, Le Corbusier’s former mentee, designed a three-bell portico addition to the chapel in 1970. Although he generally restricted his architectural projects to modular and prefabricated housing solutions aligned with his progressive politics, Prouvé was contacted directly by the chaplain and asked to design the bell tower that was left unfinished with the death of his late mentor in 1965. Prouvé expressed significant reservations with taking on the task, “It was very difficult for him because he feared the confrontation between the overwhelming presence of Le Corbusier’s work and his personal contribution.” After carefully vetting the project’s requirements, Prouvé designed a simple, unobtrusive metal structure that affords the three bells full range of motion, allowing the chimes to reverberate throughout the valley.

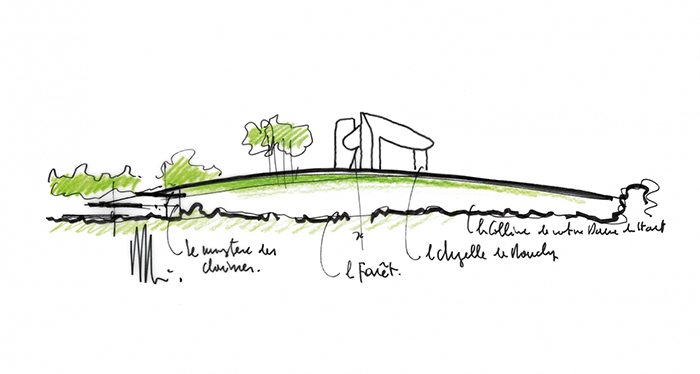

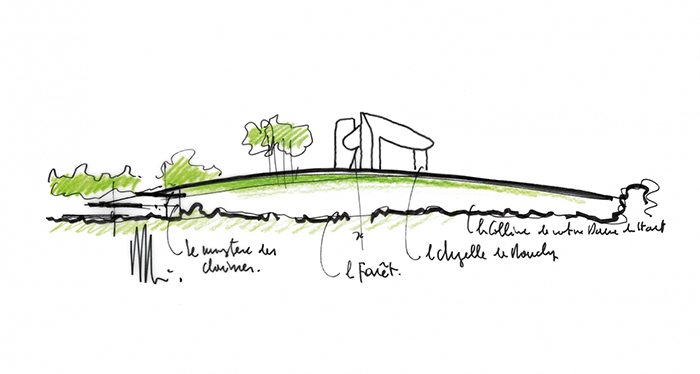

Renzo Piano's sketch for Monastery for the Sisters of St. Claire. Photograph ©RPBW, 2013.

Renzo Piano, the 1998 recipient of the Pritzker Architectural Prize, devised the tourist entrance pavilion and the Monastery for the Sisters of St. Claire at the foot of the hill. Known for his sparse use of architectural deliminations (e.g. walls, ceilings, and columns), Piano relies heavily on non-material elements to accent aesthetic features of the natural and man-made environment. In his own words, “The wealth of the area is [found] in the elements, such as light, colour, and vegetation.” Accordingly, Piano’s footprint can be difficult to identify, since his contributions to the space can be seen as subtractive rather than additive.

For information on visiting the compound, please visit Colline Notre-Dame du Haut’s website.