Philip Johnson's Thesis House

Ash Street House is a testament to visionary architect's modernist roots.

“I like the thought that what we are to do on this earth is embellish it for its greater beauty, so that oncoming generations can look back to the shapes we leave here and get the same thrill I get in looking back." -Philip Johnson.

Harvard’s Graduate School of Design has recently curated an exhibition on Philip Johnson’s first architectural project, Ash Street House, also know as “Thesis House,” after he submitted it for his Masters of Architecture thesis. The exhibit includes a pop-up lounge of Knoll’s Barcelona Collection (after Johnson’s original configuration of the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe-designed furniture he imported from Europe) along with a series of original photographs by Ezra Stoller, the accomplished architectural photographer, and Iwan Baan.

Visitors lounge in Knoll's Barcelona Chair and Couch. The arrangement mirrors Johnson's original configuration of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's iconic furniture line. Photograph by Ira Garber.

Although he studied history and philosophy as an undergraduate, Philip Johnson felt the pull of architecture during the extended trips to Europe that punctuated his studies. After visiting the Parthenon, the Chartres Cathedral, and other ancient monuments, he fell in socially with the now-towering figureheads of modern architecture, including Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe. Exposure to their ideas, works, and philosophy led Johnson to become a devotee of the Modernist movement. After returning from his sojourn abroad, he set about arranging the exhibition that would present their body of work as a cohesive corpus. In 1932, “International Style: Architecture since 1922” debuted at The Museum of Modern Art to great aplomb and introduced the modern architectural movement to America.

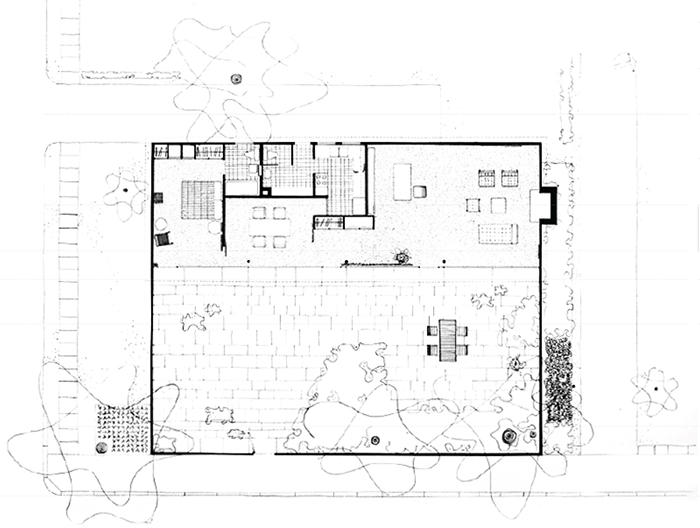

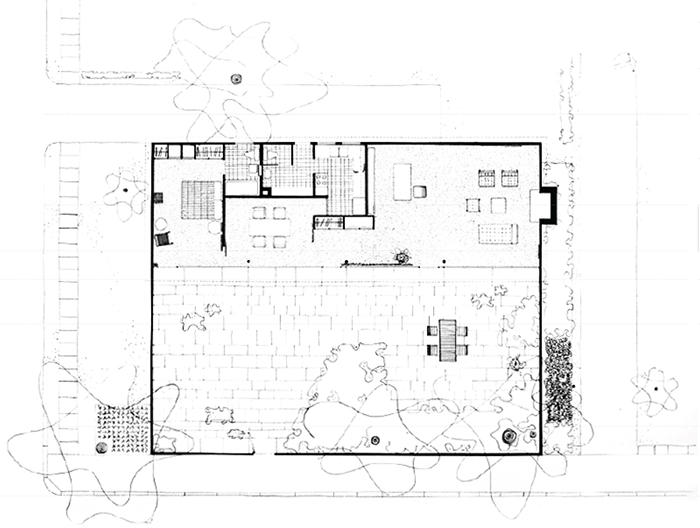

Plan of Philip Johnson's Thesis House, drawn by Wilhelm Viggo von Moltke in 1941-1942, Image courtesy of Columbia University's Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library.

Even after the success of the 1932 exhibition, it wasn’t until seven years later that Johnson decided to pursue architecture through formal schooling, enrolling at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 1940. He bought an acre plot of land at 9 Ash Street in Harvard Square, Cambridge and set about synthesizing his disparate influences in what would become his first architectural project. The following summary of the house’s construction is courtesy of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design:

“The design of the house went through several iterations, but Johnson found his early attempts limited by a wartime shortage of building materials. Despite these challenges, Johnson continued with his own design and constructed a pre-fabricated structure made of Weldtex, a hollow plywood panel finished with a striated textured veneer that could be used indoors or outdoors.

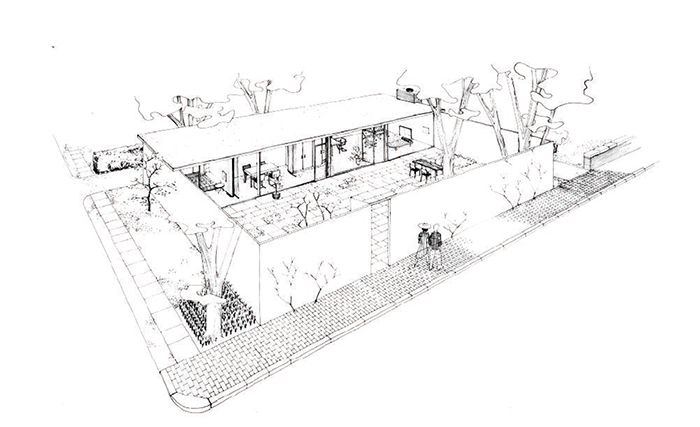

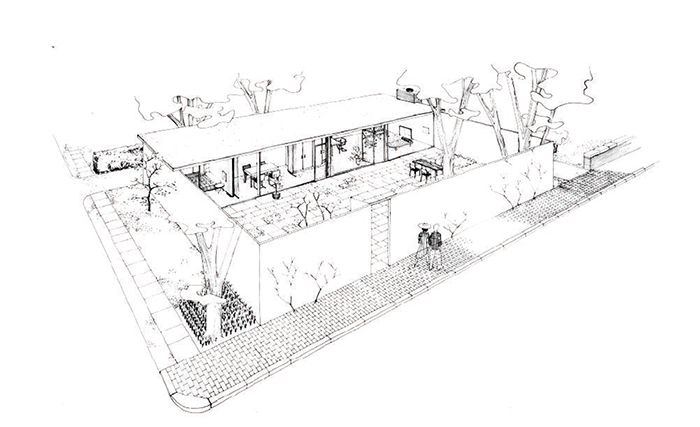

Johnson’s final design was comprised of two parts: a rectangular house and a courtyard enclosed by a high perimeter fence that corresponds in height to the house’s walls. The fence’s door opens from the street into the private courtyard, which is separated from the interior of the house by a glass and steel façade. The interior spaces are open and flow into one another.”

"Pop-up" Installation of Knoll's Barcelona Collection. Photograph by Ira Garber.

The fundamental importance of the relationship between the house’s architectural exterior and the lines of its interior furnishings is on full display in the exhibition, with Johnson utilizing an arrangement of Barcelona furniture comparable to that canonized in his Glass House. Johnson, himself, went on to define architecture with respect to interior space, introducing the dialectic that would become characteristic of much of his later work: “Architecture is basically the design of interiors, it’s the art of organizing interior space.” This concept of architecture as interior space explains the nine-foot tall fence that effectively cuts the building off from the surrounding neighborhood while simultaneously incorporating the courtyard into two thirds of the available acreage in the design plan.

Sketch of Philip Johnson's Thesis House by an unknown artist. Image from Built in USA 1932-1944 edited by Elizabeth Mock and published by MoMA.

Thus, Johnson’s Thesis House functioned, in many ways, as a template for subsequent projects early in his career in the period leading up to his collaboration with his mentor, Mies van der Rohe, on the Seagrams Building. Those buildings include the Booth (or Damora) House, the John de Menil House, and, of course, the Glass House.

For more information on Thesis House and the current exhibition, please visit Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. The exhibit will be on display through December 18th, 2014.