From The Archives: Window Displays

Two photographs from the Knoll archives document a past collaboration with Saks Fifth Avenue

Luxury retailers have long been known for their inventive window displays, hiring full-time staffers to think up and implement ideas designed to get jaded city dwellers to stop in their tracks and contemplate an array of covetable items.

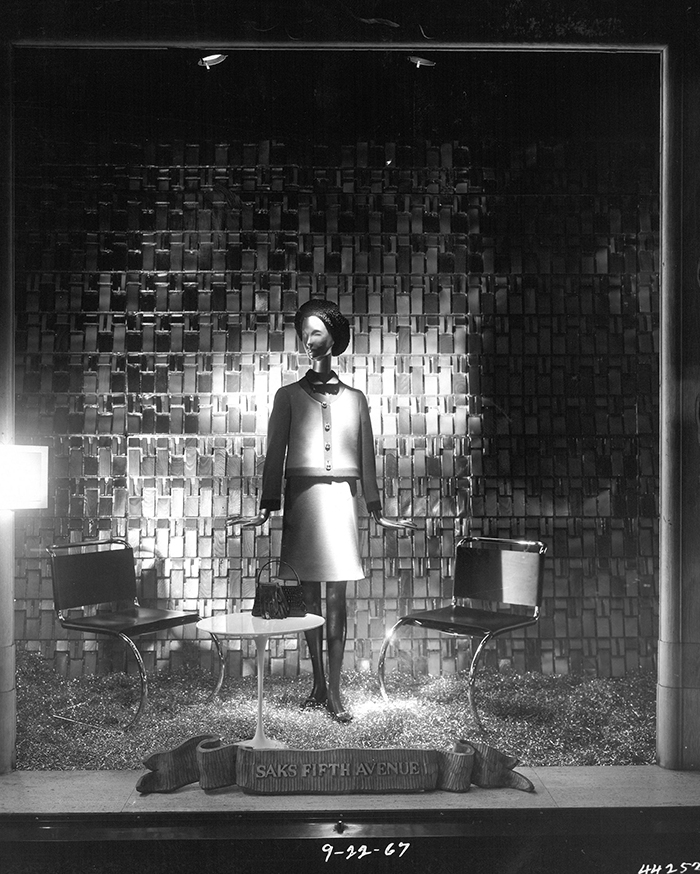

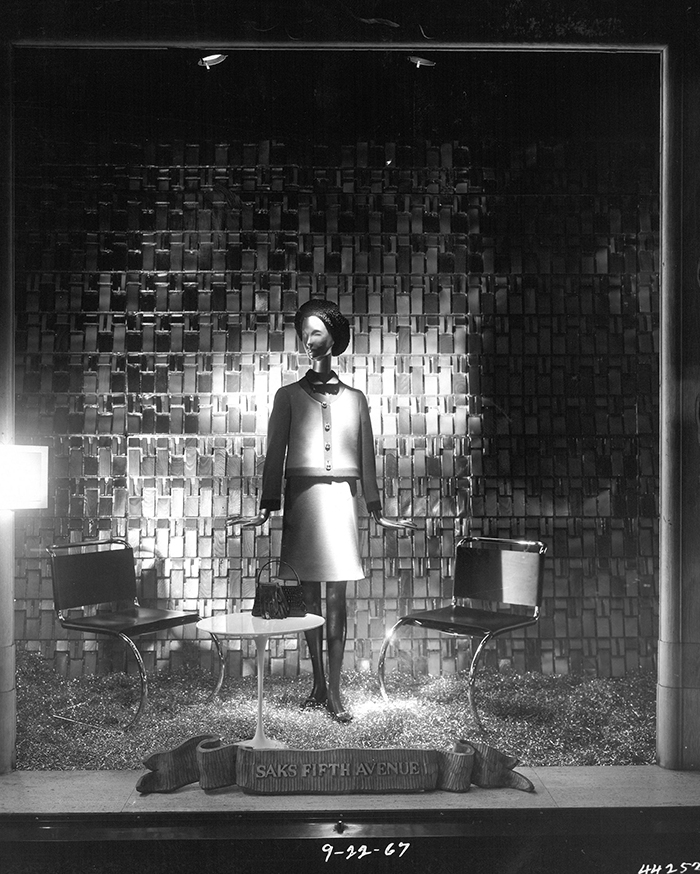

In 1967, Saks Fifth Avenue collaborated with Knoll to advertise the season’s latest collection. The displays forefront the retailer's couture costuming department, pushing the newest iteration of the dress-cum-jacket against the backdrop of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona and MR Collections. The images provide an interesting occasion to consider the legacy of Modernism, advertising’s Golden Era, and women's evolving workplace wardrobe.

Saks Fifth Avenue Window Display, 1967. Image from Knoll Archives.

The plaque in the window reads: “Our exclusive couture costuming supplants the suit,” perhaps alluding to the ascendance of women in the workplace. However, it's more likely that the copy is referencing the latest fashion: the female pantsuit. Taken just a year after the debut of Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking Collection – which contraversially put forth the pantsuit as an acceptable, albeit masculine style for women to wear – these photographs attest to the staying power of the predominant style, a coat paired with a matching skirt or dress. The mannequins, contra Yves Saint Laurent’s couture, define the look of the 'modern woman' as streamlined and professional, while remaining distinctly feminine.

Saks Fifth Avenue Window Display, 1967. Image from Knoll Archives.

Although the mannequins take the spotlight, they assume architectural rather than natural poses, interacting with the Knoll pieces that frame their positioning. In the more dynamic of the two arrangements, a raised arm and extended leg continue the extrapolated line introduced by the Barcelona Chair’s stainless-steel base. The Chanel-style jacket is unbuttoned and upturned, suggesting an imaginary wind. Meanwhile, the adjacent mannequin’s statuesque pose is reinforced by its buttoned-up appearance, with flat hands extending out toward the seats of the cantilevered MR Chairs. The costumes’ purses and color-coordinated gloves sit regally atop a Saarinen Side Table and Barcelona Ottoman, isolated from their implied owners.

Florence Knoll wearing a jacket and matching skirt in the company of (counter clockwise) Harry Bertoia, Herbert Matter, and Hans Knoll. Image from the Knoll Archives.

Both looks (sans hats) are, interestingly enough, an accurate reflection of Florence Knoll’s everyday uniform. As an interpreter of the Modernist movement, Knoll sought to extend the ethos and aesthetic of modern architecture to interior spaces (both corporate and domestic). Slim, spare, and textural are terms that refer to her furniture designs as well as her personal wardrobe. In advocating for a consistent visual language across all spaces, it's clear that Knoll saw that philosophy as equally applicable to clothing.

Herbert Matter, seated diagonally across from Florence Knoll, oversaw all of Knoll's branding, identity, and marketing efforts throughout the so-called Golden Age of advertising. He left the company in 1966, one year before the Saks photographs were taken. By 1967, Robert Cadwallader, the newly appointed head of marketing, had named Massimo Vignelli, the typographer and graphic designer, to be Matter's successor. The time signaled a period of great change for Knoll, that culminated in the formation of Knoll International in 1968. Within that time frame, Massimo rebranded and standardized Knoll's corporate identity – elements of which still persist to this day – while Cadwallader explored new marketing opportunities. It was most likely during this transition that the collaboration with Saks Fifth Avenue came to fruition.

Herbert Matter's 'Chimney Sweep' campaign for Eero Saarinen's Womb Chair. Image from Knoll Archives.

However, during his twenty-year tenure, Matter created many of Knoll's most memorable and iconic campaigns, including the 'Chimney Sweep' advertisement for Eero Saarinen's Womb Chair. Combining Swiss innovations in typography with the graphic sensibility of the Russian Constructivists, Matter's collage style stood out in the 1950s marketplace and helped differentiate Knoll in the heyday era of corporate ad spend. Having studied painting with Fernand Léger, Matter's affinity for the art world explains his creative edge in the commercial sector. He was close friends with many of the New York School's most prominent painters, photographers, and sculptures including Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Frank, Alexander Calder, and Alberto Giacometti. As a result, Matter was exposed to a constant stream of methods, materials, and ideas that helped inform his own innovative use of photomontage.