The history of graphic design at Knoll is largely the result of two legacies: that of Herbert Matter and Massimo Vignelli. While Matter worked in the 1950s and 60s and Vignelli took over in the 1970s, each designer developed an enduring graphic identity for Knoll, both stringent in their consideration of the smallest details—from the width of the elongated slab serif “big K” logo to the modular dimensions of the price lists to the precise saturation of Knoll Red. But while Matter and Vignelli are remembered for their consistent approach to graphic design at Knoll, their tendency towards aesthetic unity did not originate with them. The pair shared this preference with their predecessor, a third graphic designer named Alvin Lustig.

A gifted designer whose work included graphics, packaging, typography, architecture and interiors, Alvin Lustig brought his inimitable style to Knoll for a short but impactful moment in the then-nascent company’s history. While his recognition lies mainly in the realm of book jacket design, Lustig's work in advertising and brand identity drew from the same modernist influences. “To hire Lustig was to get more than a cosmetic makeover,” art director and historian Steven Heller writes. “He wanted to be totally involved in an entire design program—from business card to office building.”

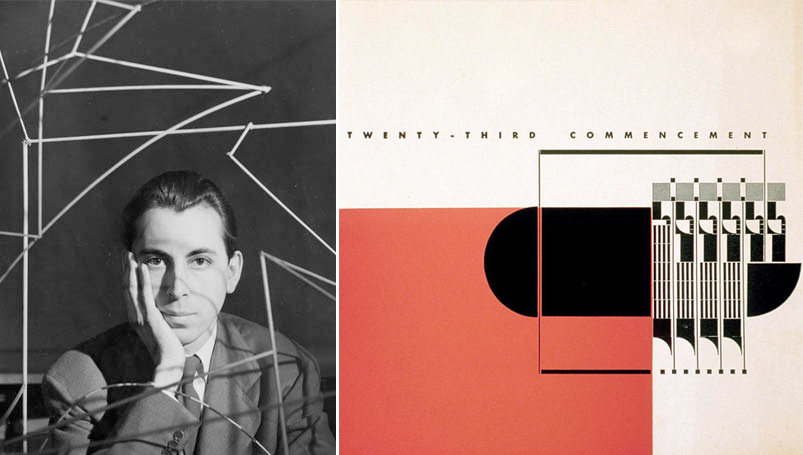

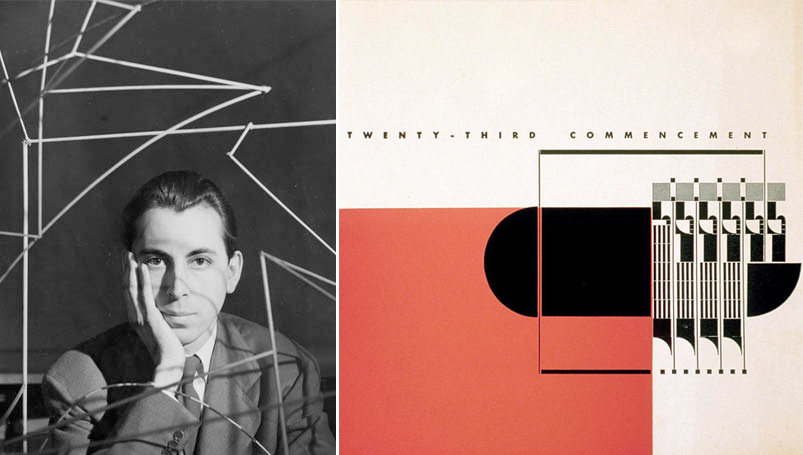

Left: Alvin Lustig. Photograph by Maya Deren. Right: Lustig's cover for the 23rd commencement brochure of Beverly Hills High School, 1940. Images courtesy of the Alvin Lustig Archive.

Born in Denver, Colorado, in 1915, Lustig had no intentions of becoming a designer. After his family moved to Los Angeles, he began skipping classes to perform as a magician in school assemblies around the city. But when a teacher exposed him to an emerging brand of European modern art, Lustig’s career trajectory was forever altered. He became enraptured by the unburdened quality of avant-garde design, which shed the weight of unecessary ornament and the canon of decorative arts that preceded it.

“This ability to ‘see’ freshly, unencumbered by preconceived verbal, literary or moral ideas, is the first step in responding to most modern art,” he later wrote in his personal notes. Following the initial encounter, Lustig began to devote more time to designing posters for his magic shows than to practicing tricks. At the age of 21, he began to work freelance on a letterpress out of the backroom of a drugstore. Making improvised geometric patterns using pieces of metal type, Lustig reconciled the abstract, economical tenor of highbrow modernism with the more quotidian formats of graphic design.

“To hire Lustig was to get more than a cosmetic makeover. He wanted to be totally involved in an entire design program—from business card to office building.”

—Steven Heller

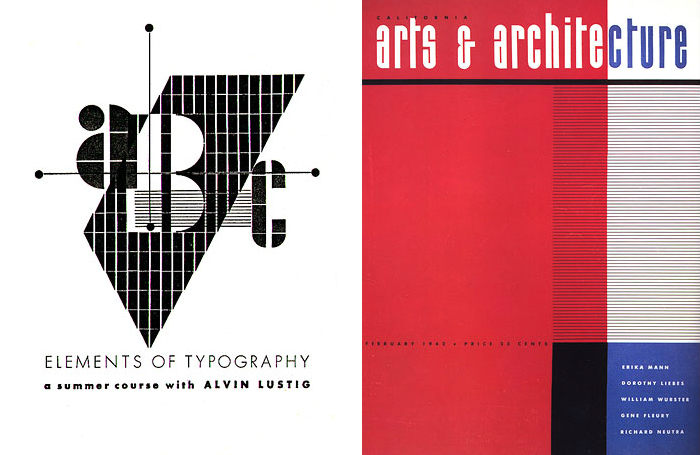

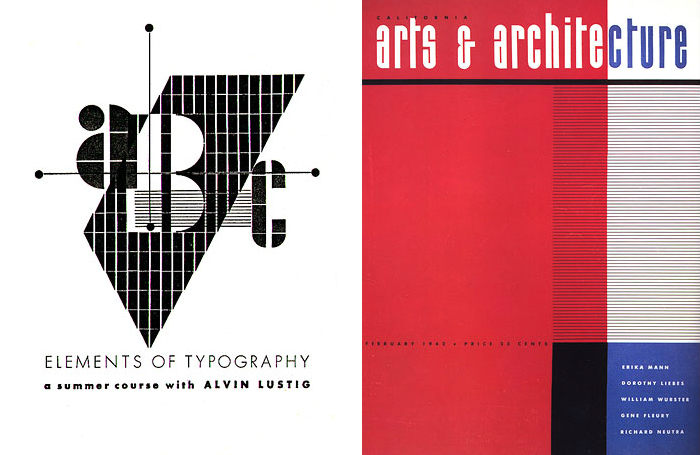

Left: Poster for a summer course at the Arts Association of LA, 1941, designed by Alvin Lustig. Right: Lustig's cover for Arts and Architecture magazine, 1942. Images courtesy of the Alvin Lustig Archive.

In 1944, the young printmaker left California for a two-year stint in New York as the visual research director for Look magazine. It was then typical for designers to delve into advertising in order to stay afloat, and it was during this period that Lustig began to dabble in advertising.

He arrived on the cusp of a new era in the ad industry, a period between the influence of famed graphic designer Paul Rand and before the full-blown “Creative Revolution” of the 1950s. It was still a point in time when “copywriters ruled the roost,” Heller notes, and “design was usually an after-thought.” Luckily for Lustig, “creating advertisements may have required a slightly different mindset but demanded the same refined compositional flair.” His modernist dexterity could straddle many mediums.

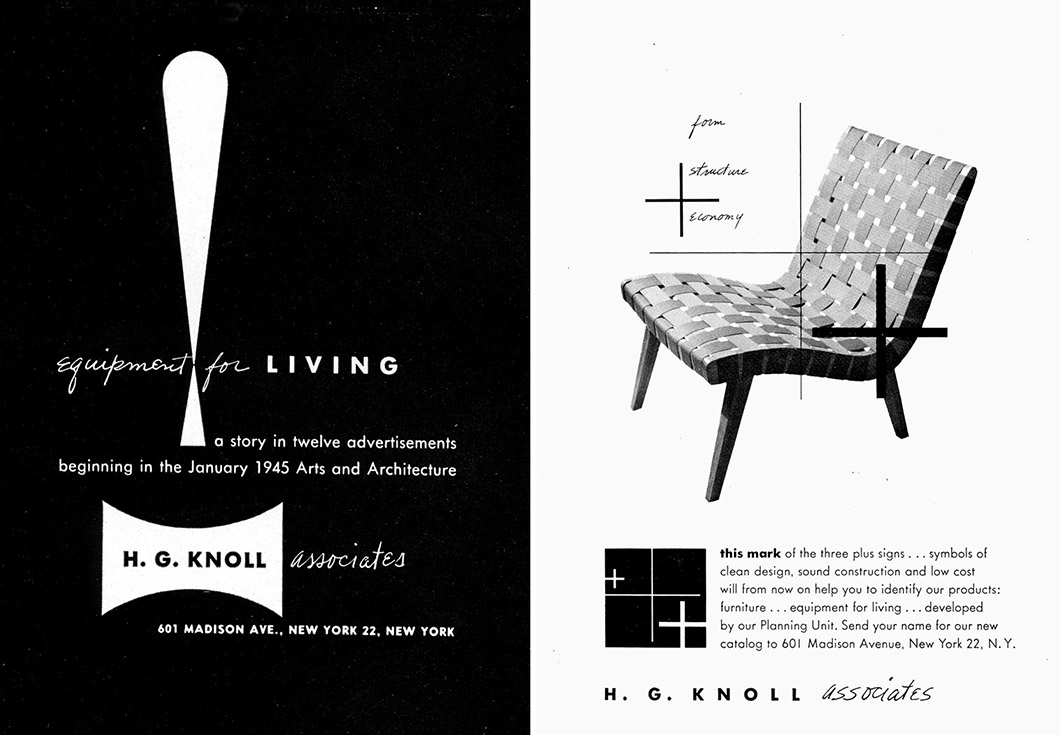

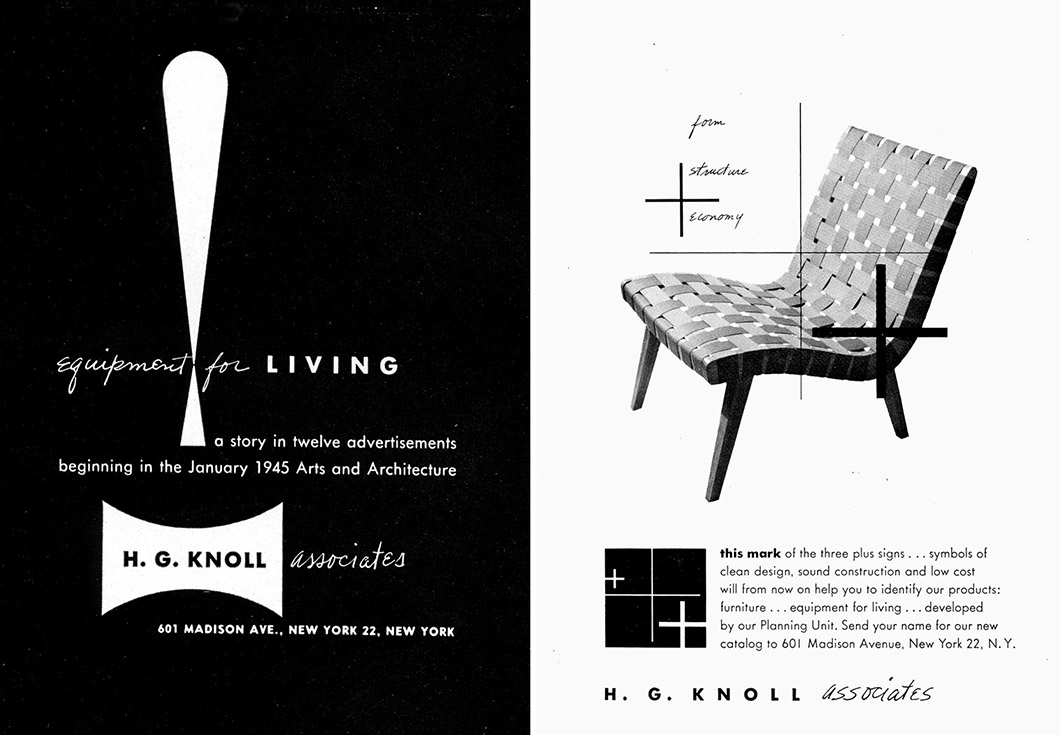

Left: Announcement of the 1945 Hans G. Knoll Associates advertisement campaign in Arts and Architecture, designed by Alvin Lustig. Right: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designed by Alvin Lustig, Arts and Architecture, January 1945. Images courtesy of the Alvin Lustig Archive.

In a shared commitment to the pioneering aesthetics of modernism, Hans Knoll saw in Lustig someone who could translate the new vision for his company, still under the moniker of Hans G. Knoll Associates, into printed publicity. After a few years selling imported European furniture to an American market, Knoll had recently shifted gears—he bought a factory in East Greenville, Pennsylvania and brought in Danish designers Jens Risom and Abel Sorensen to design Knoll’s first collections of original furniture.

Commissioned by Hans Knoll, Lustig designed a series of twelve full-page ads collectively called “Equipment for Living,” which were to be published in successive issues of the influential Arts and Architecture magazine beginning in January 1945. The yearlong campaign combined monochrome photographs of furniture—including designs by Risom, Sorensen, and the latest line of furniture by Ralph Rapson—with black line work and sans serif text, each one professing some or all of the company’s virtues: economy, form, structure.

Left: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designed by Alvin Lustig, Arts and Architecture, February 1945. Right: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designed by Alvin Lustig, Arts and Architecture, March 1945. Images courtesy of the Alvin Lustig Archive.

Left: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designed by Alvin Lustig, Arts and Architecture, April 1945. Right: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designed by Alvin Lustig, Arts and Architecture, May 1945. Images courtesy of the Alvin Lustig Archive.

Lustig often manipulated images of the chairs, isolating their parts, overlaying them atop shapes and line drawings, and transforming them into intriguing abstract patterns. To publicize Knoll’s newly formed Planning Unit and its personality of rational, refined design, Lustig saw a narrative in the simplicity of a plus sign: “This mark of the three plus signs,” one advertisement read, “symbols of clean design, sound construction and low cost will from now on help you to identify our products: furniture … equipment for living … developed by our Planning Unit.”

Left: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designed by Alvin Lustig, Arts and Architecture, June 1945. Right: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designed by Alvin Lustig, Arts and Architecture, July 1945. Images courtesy of Arts and Architecture.

The young graphic artist steadily amassed a roster of clients in the furniture and interiors business—clients who, according to Heller, “understood that being modern was essential to piquing the interests of their customers.” For them, Alvin Lustig, with his interdisciplinary expertise, was the ideal graphic interpreter of their progressive ethos.

Left: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designer unknown, Arts and Architecture, August 1945. Right: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designer unknown, Arts and Architecture, September 1945. Images courtesy of Arts and Architecture.

Left: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designer unknown, Arts and Architecture, October 1945. Right: Advertisement for Hans G. Knoll Associates, designed by RJ Wolff, Arts and Architecture, November 1945. Images courtesy of Arts and Architecture.

But eventually, Lustig’s relationship with Knoll reached its end, his work appreciated but out of step with the pace of a loosening post-war aesthetic. “The thrust of many Lustig ads had been directed toward economy,” historian Eric Larrabee writes, but “as furniture began to change, emerging from wartime severity, the style and tone of the ads changed also, in a manner that was much of Matter’s doing.” It appears he did not finish the 1945 ad campaign himself. The August, September, and October advertisements—though similar in style to Lustig's work—were not made by him, the November advertisement was attributed to RJ Wolff, and the December issue repeated a previous Lustig design.

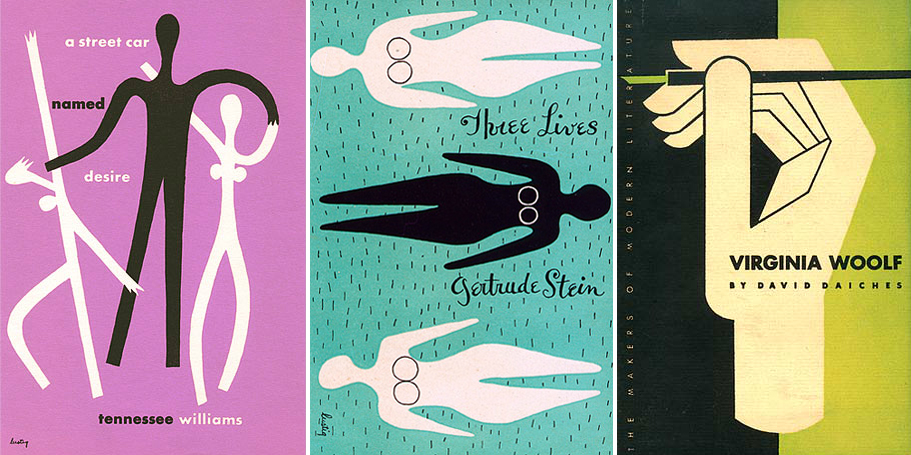

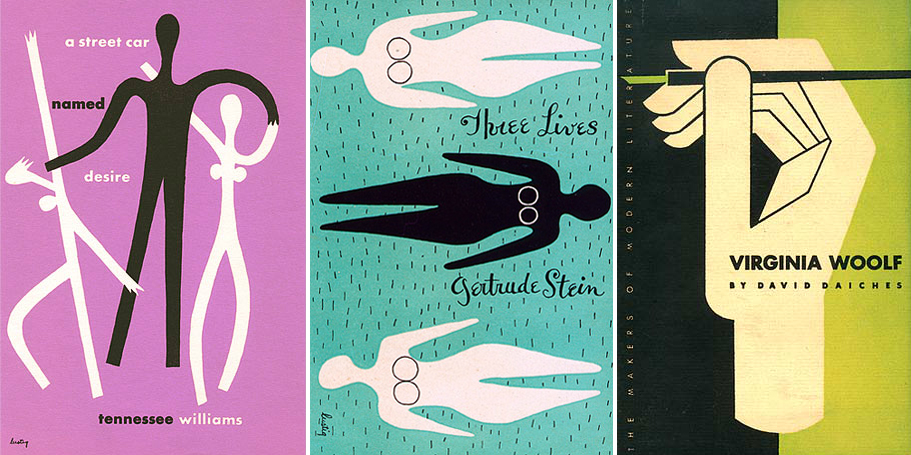

Book jackets designed by Alvin Lustig. Images courtesy of the Alvin Lustig Archive.

“The thrust of many Lustig ads had been directed toward economy... [but] as furniture began to change, emerging from wartime severity, the style and tone of the ads changed also, in a manner that was much of Matter’s doing.”

—Eric Larrabee

Taking his talents back to Los Angeles in 1946, Lustig opened an interiors firm and continued a prolific career in design, particularly for publishers Meridian Books, Noonday Press, Knopf, and New Directions. His playful compositions for book jackets displayed the same unprecedented blend of typography, collage, and color that the designer had once brought to Knoll. Although ostensibly unable to satisfy the evolving vision of Florence Knoll and phased out for the more involved participation of Herbert Matter, Alvin Lustig’s unapologetic modernism synchronized perfectly, if briefly, with the ideals of the growing furniture brand.