From The Archive: Ettore Sottsass

Revisit the postmodern designs of the Austrian-born Milanese architect

“Everything must remain possible.”

—Ettore Sottsass

Ettore Sottsass, who worked with Knoll on three collections between 1983 and 1988, wanted to be everything that modernism wasn’t. The founder of a half dozen design collectives—including Giuseppe Pagano, Memphis Group and Sottsass Associati—Sottsass became known for his asymmetric forms and, perhaps most of all, his flamboyant use of color, often in bold, clashing combinations. “You don’t save your soul just painting everything in white,” he once wrote. “Color can arise and be in harmony with the imperatives of structure, without destroying it.”

A noted polymath and precocious youth, since his early years Sottsass has been driven by insatiable curiosity. His passions and practices are not limited to photography, painting, graphic design, sculpture, interior design, ceramics, found art, and writing. Such diverse pursuits became unified by Sottsass’ disavowal of the rigidity of the modernist movement that was de rigueur during his formative years at Politecnico di Torino in Turin, Italy. According to the art historian Barbara Radice, who would later become Sottsass’ wife: “While still young, Sottsass learned that the ‘beauty,’ ‘formal correctness,’ ‘coherence,’ ‘function,’ even the ‘utility” of an object were not absolute, metaphysical values, but that they responded to a culture or a system, and varied in accordance with historical and cultural conditions.”

Eastside Collection by Ettore Sottsass, 1986. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

In his time, Sottsass was reviled by many, although championed by a vocal few, most of them affiliated with the civil and cultural unrest of the 1960s and 70s. Advocating that “everything must remain possible,” Sottsass effectively translated the attitude of counterculture into the realm of design. His studio apartment hosted noted luminaries of the Beat generation, including Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac and Bob Dylan. It was, in fact, Dylan’s “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” that provided the name for Sottsass’ most well-known design collective. (Supposedly, during the group’s first meeting, the song was playing in the background when the needle got stuck on the last three words of the title.) When Memphis debuted its first collection of furnishings at Milan Salone, a riot nearly erupted among the two-thousand odd attendees.

“Color can arise and be in harmony with the imperatives of structure, without destroying it.”

—Ettore Sottsass

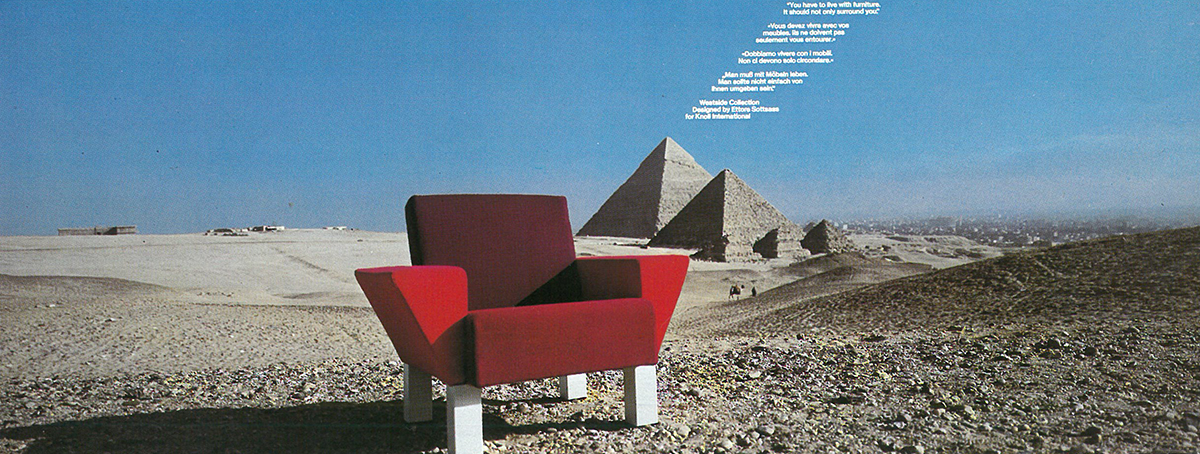

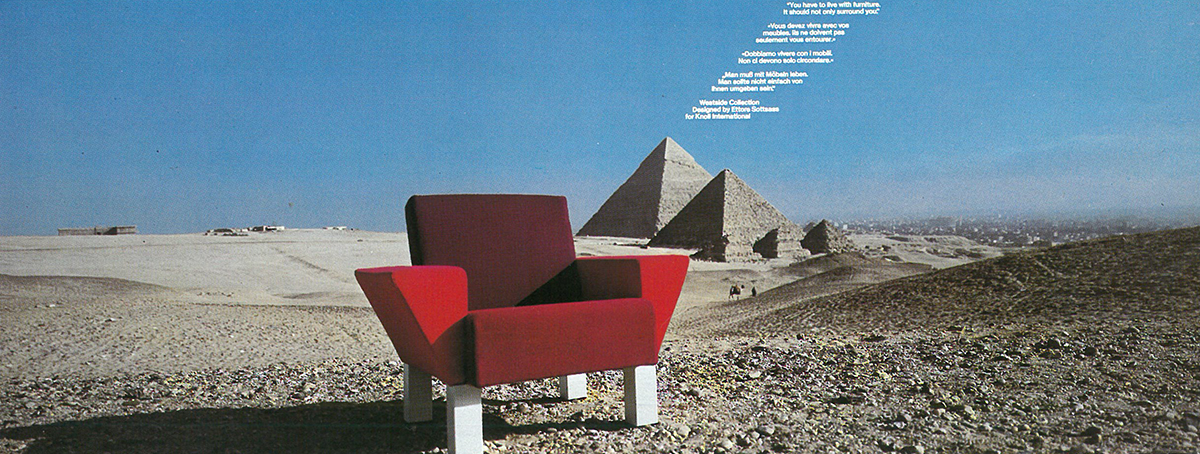

Detail of the Westside Collection by Ettore Sottsass for Knoll Studio on the cover of Graphis. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

In 1983, two years after the founding of Memphis, Sottsass splintered off from his collective to partner with Knoll Studio, creating the Eastside and Westside collections. Inspired by his lifelong love of Viennese Biedermeier chairs, characterized by plush seats with clean lines and minimal adornment, the collection consisted of geometric sofas and lounge chairs in color-blocked upholsteries. In spite of his iconoclasm, Sottsass had a deep appreciation of ancient art and architecture—particularly Sumerian, Assyrian and Chinese—resulting in the decision to shoot the collection against the backdrop of the Great Pyramids of Giza.

Westside Lounge Collection by Ettore Sottsass for Knoll Studio. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

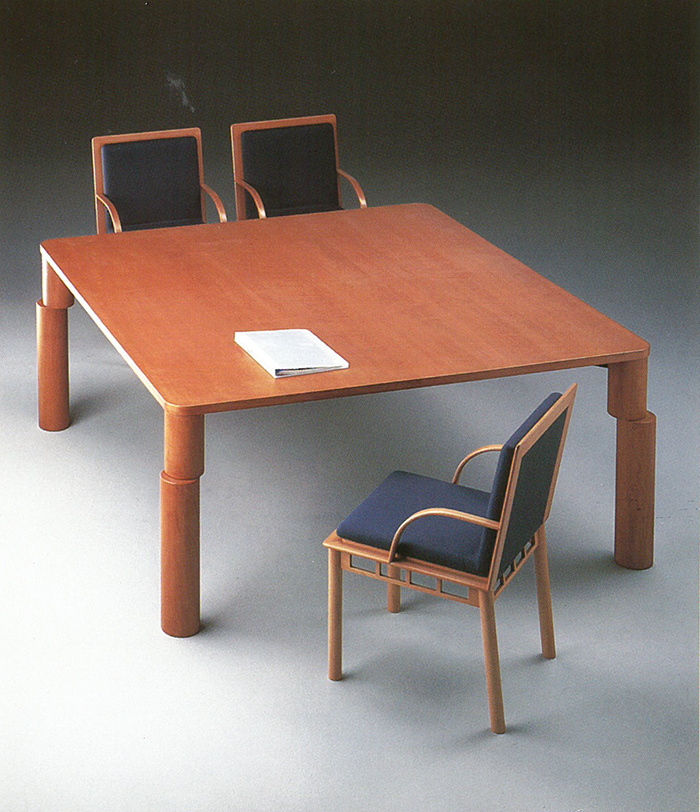

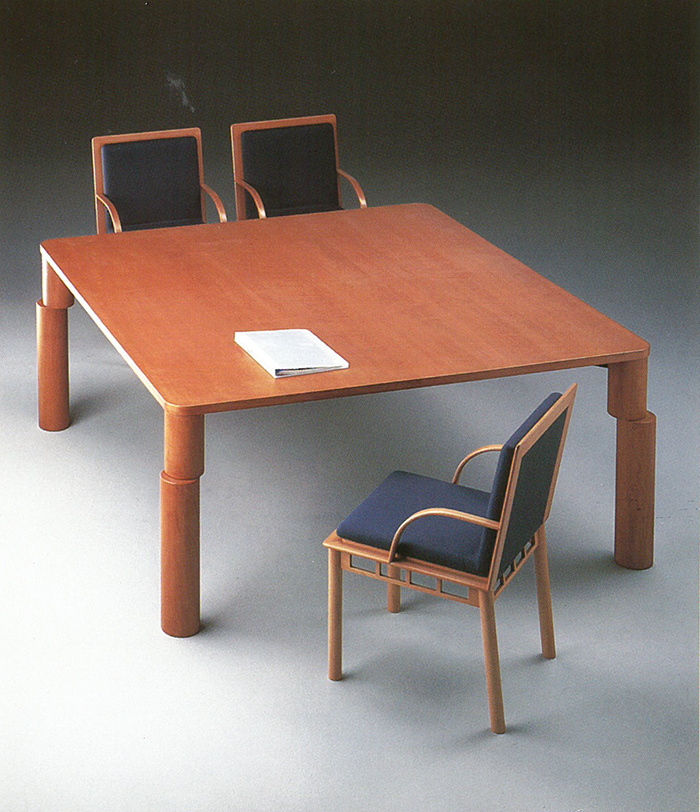

With the success of the Eastside and Westside collections, Sotsass returned to work with Knoll in 1986. His Spyder Table and Mandarin Chair, billed as a pair, date from that period.

“Sottsass learned that the ‘beauty,’ ‘function,’ even the ‘utility’ of an object [...] varied in accordance with historical and cultural conditions.”

—Barbara Radice

Mandarin Chair by Ettore Sottsass for Knoll Studio, 1986. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

The Mandarin Chair was a particular favorite for corporate interiors, restaurants and libraries. Its flowing, sculptural arm invoked the turn-of-the-century bentwood designs of Thonet, and was available in a variety of different color finishes that afforded the design a level of adaptability. As the original press release noted, “The chair’s character changes with its finishes, from high-tech to traditional.”

Spyder Table and Mandarin Chair by Ettore Sottsass for Knoll Studio, 1986. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

The Shift Table and Bridge Chair soon followed suit. Characteristic of Sottsass’ irreverence toward classical structure, the Shift Table featured a bisected leg that gave the appearance of precariously stacked columns supporting the table—the two pieces were held together by concealed steel pins. The Bridge Chair was named after the structurally functional “bridge” between the upright legs, referencing the stylistic details first popularized by Frank Lloyd Wright, historically indebted to Japanese design. In this sense, Sottsass continued to quote, in a tongue-in-cheek manner, tropes of beloved and accepted architecture and furniture, intelligently.

“Sottsass’ abiding aim has been not to remake the world in the image of design but to remake design in the image of the world.”

—Herbert Muschamp

Bridge Chair and Shift Table by Ettore Sottsass for Knoll Studio, 1988. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

Herbert Muschamp, the late architectural critic for The New York Times, perhaps best articulated the impulse that has guided Sottsass' varied career when he wrote: “Sottsass’ abiding aim has been not to remake the world in the image of design but to remake design in the image of the world.”

All photographs are courtesy of the Knoll Archive unless otherwise noted.