The Soul of A Tree

Inside George Nakashima's New Hope home, studio and creative compound

“There must be a union between the spirit in wood and the spirit in man,” said George Nakashima, intoning the philosophy undergirding his world-renowned woodworking practice. As one of the great designers and craftsmen of the twentieth century, George Nakashima’s home, studio and creative compound in New Hope, Pennsylvania, is both a testament to his unique vision and the venerable workspace where he created furniture designed to bring nature into the modern home.

Photographed by Don Freeman as part of his book Artists’ Handmade Houses—which catalogues thirteen hand-crafted houses by the likes of George Nakashima, Russell Wright and Paolo Soleri—the compound is presented here as an extension of Nakashima’s craft and philosophy. “I tend to search out the very odd, unusual and romantic in a house,” says Freeman of his particular approach. “It’s important for me when I photograph a home to be the quiet visitor in the room, aware of natural light, the compositions that the furniture and objects make up in the interior, and the situation within its environment.”

George Nakashima's home in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Don Freeman.

Nakashima was born in Spokane, Washington, although he went on to live “almost every place else,” including Japan, France and India. In spite of his cosmopolitanism, much of his practice is indebted to the verdant environment of the Pacific Northwest. According to Mira Nakashima—not only the daughter and sole heir to George Nakashima’s legacy, but also the head of the contemporary Nakashima Woodworkers enterprise and a designer in her own right—“It was a Boy Scout leader who inspired him to go on these long hikes and camping trips. It was beautiful, and he fell in love with trees then and there.”

“He turned to furniture because he thought of it as architecture in a microcosm.”

—Mira Nakashima

George Nakashima's home in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Don Freeman.

In school at the University of Washington, Nakashima studied forestry before transferring to the architectural department after two years. His inimitable talent garnered him a scholarship to Harvard, which he then transferred to M.I.T. Upon graduating, he worked for Antonin Raymond—a disciple of Cass Gilbert and Frank Lloyd Wright, who combined Japanese building techniques with American technical innovations—in New York and Paris before Tokyo, designing interiors for the firm’s various projects. “Dad wasn’t happy with the dis-integration of the [architectural] process,” says Mira. “When he came back to this country, he saw Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings under construction and thought that they hadn’t been designed, or executed very well.” As a result, Nakashima decided to devote himself to furniture, a discipline that would not require him to forfeit control of any aspect of production. “He turned to furniture because he thought of it as architecture in a microcosm.”

George Nakashima's Art's Building in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Don Freeman.

When the bombing of Pearl Harbor heralded the U.S. entry into World War II, Nakashima was interred, along with tens of thousands of other Japanese Americans, in an internment camp. While there, Nakashima made the most of the experience by training and collaborating with a Japanese woodworker using scrap supplies to create his some of his earliest designs. “I still have a box he made for me when we were in camp,” adds Mira.

“I think he thought it was kind of prophetic that the place was called ‘New Hope.’ He basically had nothing to lose by staying here, so he stayed.”

—Mira Nakashima

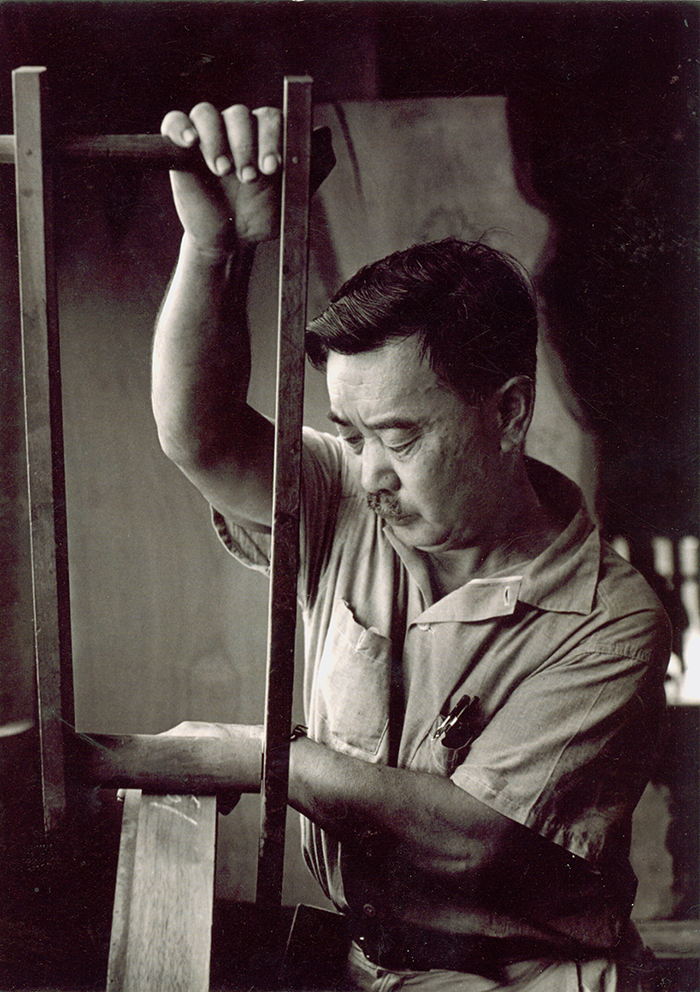

George Nakashima crafting at Camp Minidoka, 1942. Photograph by Francis Stewart. Courtesy of UC Berkley Bancroft Library.

With the sponsorship of his former employer, Nakashima was able to extricate himself from the camp in 1943, and moved to stay with Raymond at his farm in New Hope. Since Raymond was working on government contracts as part of the allied war effort, Nakashima was relegated to chicken farming, having been forbidden from practicing architecture by the U.S. government. It was during that time that “he realized there was an artist’s community, the so-called New Hope Impressionists” and began making preparations to launch his furniture career from New Hope after the war. “I think he thought it was kind of prophetic that the place was called ‘New Hope,’” Mira speculates. “He basically had nothing to lose by staying here, so he stayed.”

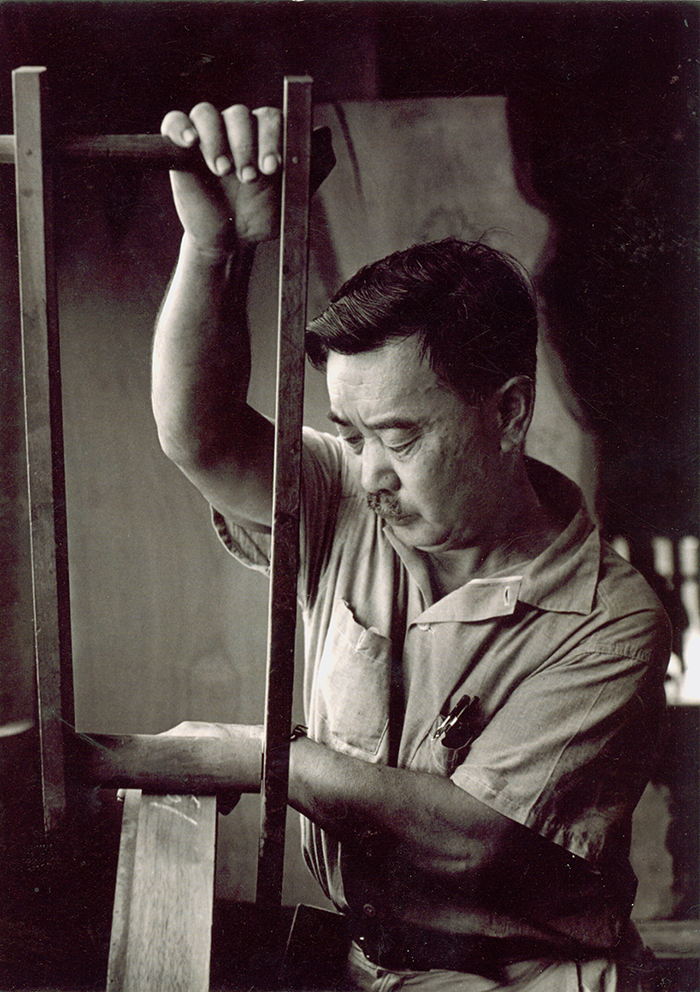

George Nakashima working in his studio. Photograph from Knoll Archive.

With few resources, Nakashima had to rely on his architectural training to provide a roof for his family. Each one of the fourteen buildings that make up the compound today was hand-built by Nakashima over the course of the next thirty years. “The first building was the shop. Dad found this land on a south-facing slope and he didn’t have the money to buy it, so he bartered labor as payment for his first three acres. He knew that the only way he could make a living was to make a shop first. Then my mother and I needed a place to stay so he built the house second, around 1946. All this was done on a very limited budget—most of the early buildings are made with concrete block and corrugated transite.”

“The fact that he actually retained a tree’s shape and color and used the original form as part of his creative process made him something of a Japanese druid. Some might call these details ‘imperfections,’ but for him it was as if the tree was speaking.”

—Mira Nakashima

Left: George Nakashima's Straight Chair for Knoll, 1946. Photograph by Knoll.

Right: George Nakashima's Splay-Leg Table for Knoll, 1946. Photograph by Knoll.

With his studio established, Nakashima soon entered into a working relationship with Knoll, a promising but then less than a decade-old company. It was Raymond who arranged the initial introductions between Hans Knoll and Nakashima. “There’s a picture of Helen Belluschi [Jens Risom’s daughter] and me with our fathers down at Raymond farms,” says Mira of the meeting. Although an enduring skeptic of mass-production, Nakashima created two original designs for Knoll in 1946—the Splay-Leg Table and Straight Chair. Orders were originally fulfilled by Nakashima Studios, before being manufactured by Knoll out of its East Greenville facility. Nakashima retained the rights to produce the table and chair himself at a customer’s request. "So there are actually two lines, one that's handmade and one that's manufactured by Knoll."

Publicity materials for the Nakashima Straight Chair and accompanying table designed for Knoll, 1946. Photograph from Knoll Archive.

Nakashima’s designs represent the nexus of various craft-based traditions, ranging from American Shaker design to traditional Japanese joinery. Among his many celebrated forms, Nakashima Tables are cherished for their live-edge, naturalistic surface positioned atop a man-made architectural base, united in harmony. His most well-known chairs (i.e. Straight Chair and Conoid Chair) are modernist interpretations of the classic Windsor chair, with walnut seats and contrasting hickory spindles. “The fact that he actually retained a tree’s shape and color and used the original form as part of his creative process made him something of a Japanese druid,” Mira explains, “some might call these details ‘imperfections,’ but for him it was as if the tree was speaking. He was very much a part of the old Arts and Crafts movement, or the Mingei movement in Japan: hand-crafted goods, natural materials, slow processes. Some things just take time and are better because they take time; if you try to do them fast, they’re no good. He was very much aware of that quality.”

“Dad was very close with Bertoia—they had a lot of discussions about art, craft and design.”

—Mira Nakashima

A beryllium-copper sculpture designed by Harry Bertoia at George Nakashima's studio in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Knoll.

The collaboration also benefited Nakashima by bringing him into contact with other like-minded designers. He immediately recognized a kindred spirit in the sculptor and metalworker Harry Bertoia, and the two became good friends. “Dad was very close with Bertoia,” Mira recalls, “they had a lot of discussions about art, craft and design.” Several of Bertoia’s beryllium copper sculptures can be found scattered about the property today.

Exterior façade of the Conoid shell at George Nakashima's complex in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Don Freeman.

In subsequent years, as Nakashima became more and more of a household name, the property’s buildings became proportionally more architecturally inventive. Inspired by an architectural engineer he had met, Nakashima began experimenting with thin-shell construction and hyperbolic paraboloid shells. He was able to finance these more ambitious endeavors using money generated from increasingly high-profile commissions, including the Rockefeller Residential house.

“Dad used to say that the men in the shop, with all their skill and capabilities, were actually his hands. He worked through them.”

—Mira Nakashima

The production process behind the hand-made version of the Straight Chair by Nakashima Woodworkers, 2015. Photograph by Knoll.

In 1990, George Nakashima passed away, and Mira promptly picked up where her father left off, continuing to produce her father's classic designs while simultaneously developing her own novel ones. "We had a three-year backlog of orders, huge piles of wood and I decided it was too good to waste." Many of the craftsman currently working at Nakashima Woodworkers trained directly under George Nakashima for many years. “Dad used to say that the men in the shop, with all their skill and capabilities, were actually his hands," Mira recalls, adding, "he worked through them.” It appears the shop operates only slightly differently today. "The only difference is that when I change a line, I voice why I feel it should be changed. Dad would just do it."