Harry Bertoia Centennial Celebration

Knoll celebrates the enduring legacy of the sculptor and metalworker

March 10, 2015 marked the centennial celebration of the world-renowned sculptor and designer Harry Bertoia. Knoll hosted an honorary event "Bertoia at 100" in commemoration of the designer and his enduring legacy. Glenn Adamson, the Nanette L. Laitman Director of Museum of Arts and Design, gave a presentation titled "Learning from Bertoia" surveying Bertoia's large body of work.

A multi-talented artist in his own right, Harry Bertoia was part of the post-war American sculptural movement that helped free the discipline from the yoke of European influence. In the wake of the World War II, a wave of economic prosperity and industrial power resulted in significant scientific advances. Exposed to a surfeit of new industrial materials, Bertoia and his contemporaries quickly became technically proficient with the acetlyene torch, which enabled them to deftly manipulate previously untried metal alloys, wires, and plastics. Tired of the heavy forms that were dominant in the European sculptural tradition, post-war American sculptors experimented with mobile, pliable, and light forms in their work, giving birth to a new sculptural vocabulary. In pursuit of such ends, Bertoia worked in tandem with other notable innovators, including Alexander Calder and George Rickey, who incorporated kinesthetics in their mobile-like works.

Bertoia working with an acetylene torch, 1952.

Known as a gentle genius, Bertoia’s rare talent was often eclipsed by his humility and kindness, which few who had the privilege of meeting him could fail to notice. A contemporary of the Abstract Expressionists, Bertoia’s de facto demeanor could not be more opposed to the egocentric attitude of his cultural milieu. He almost never signed his work, believing his sculptural creations to be reflections of the natural world. However, it was this aspect of his personality that also resulted in a longstanding dispute with his former friend and classmate, Charles Eames. Upon graduating from Cranbrook, Bertoia spent three years working with Ray and Charles Eames and Don Albinson to bring the first plywood chair designs to the mass market. Although he helped Eames overcome numerous production difficulties associated with what is now known as the Eames Chair, Bertoia was devestated to learn that Eames had presented the collective work as an individual achievement to the Museum of Modern Art. Bertoia left Eames’ employ shortly thereafter and moved to Pennsylvania to pursue a working relationship with another Cranbook alumnus, Florence Knoll.

Bertoia working in his studio in Bally, Pennsylvania, 1952.

After partnering with Knoll, Bertoia moved to East Greenville, Pennsylvania in 1950 where he set up a metal factory in a corner of Knoll’s production facility. Knoll insisted Bertoia pursue his craft without any contractual obligations, enabling him to explore what interested him. Knoll trusted that if left to his own devices, Bertoia would produce something extraordinary. She was right. Bertoia’s eponymous furniture collection was introduced by Knoll in 1952 and instantly proclaimed one of the greatest achievements of 20th century furniture design. Bertoia’s approach to the collection was in keeping with his sculptural interests. “If you look at those chairs," Bertoia opined, "they are mainly made of air, like sculpture. Space passes right through them.” With the financial and critical success of the collection, Bertoia was able to focus on his artistic pursuits for the remainder of his life. However, Bertoia continued to be involved with Knoll, providing sculptures and installations for Planning Unit projects, including the MIT Chapel designed by Eero Saarinen.

Of his myriad talents, Bertoia always thought of himself first and foremost as a sculptor. He conceived of his secondary pursuits—which included the creation of jewelry, furniture, monoprints, and other goods—as a means of making a living while experimenting with materials and ideas. After the success of his furniture collection, Bertoia began exploring and developing a spill-casting technique, which Robert Metzger explains as a process of “pouring molten metal onto unprepared surfaces, such as loose sand or porous brick, to create surfaces that [are] biomorphic or volcanic in appearance.” The technique occupied his attention for the next decade of his life.

Harry Bertoia teaching metalworking at Cranbrook Academy, 1940.

Bertoia’s exposure to metalworking dates back to his childhood in San Lorenzo, Italy, where he was taken by the bracelets and bangles forged by the gypsies who camped out on the border of his hometown. When he took up the practice, Bertoia’s precocious talent was recognized by local brides, who took to commissioning jewelry and embroidery patterns from him. Although he initially enrolled at Cranbook as a painting student, Bertoia spent much of his time working in the shop studio which had fallen into disuse when the school’s leading silversmith, Arthur Nevill Kirk, retired. After little more than a year, Eliel Saarinen, who ran the academy, was so impressed with Bertoia’s work that he appointed him head of the studio, making him a full-time faculty member even though he was technically still a student of the college.

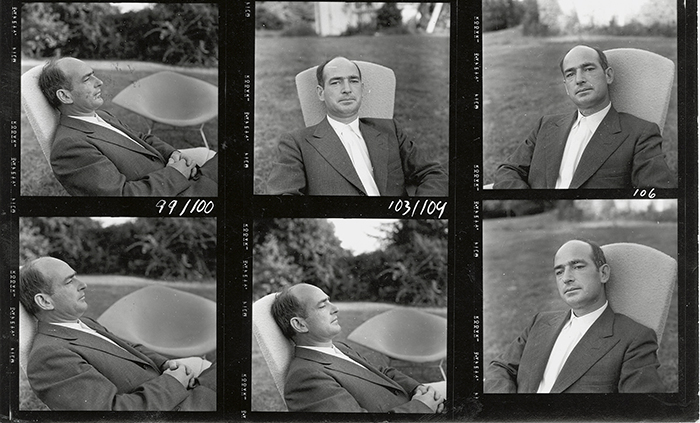

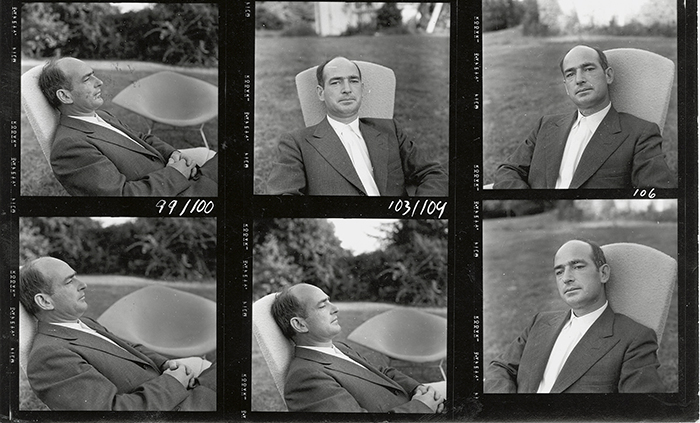

Portraits of Harry Bertoia from a photograph contact sheet for Knoll publicity materials.

Bertoia always looked to the natural world for inspiration. “If simplicity was his format, then nature was his guide,” writes Julie Longacre, a landscape designer who befriended Bertoia in 1971. To live in the countryside was a lifelong pursuit of Bertoia’s, who abhorred the trappings and technological fetters of the city. One day, upon discovering his three children glued to the TV screen, Bertoia made a show of throwing out the set. In lieu of such distractions, Bertoia preferred to listen to birds, the wind and church bells, all of which recalled the Italian countryside of his childhood. Bertoia was equally inspired by the vastness of the universe and enjoyed telling stories of celestial constellations as if intimately familiar with them.

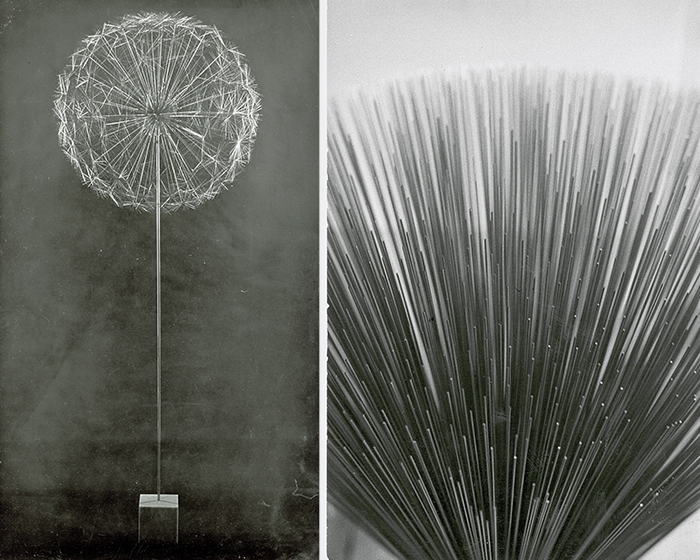

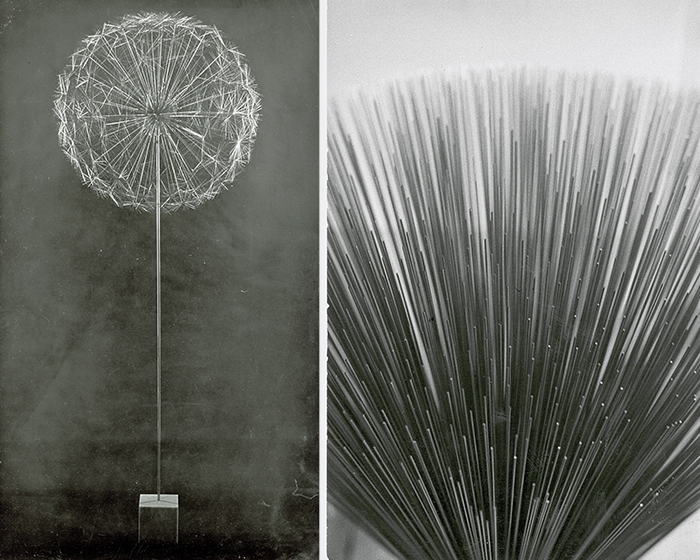

Black & white photographs of Harry Bertoia's Sonambient sculptures.

Bertoia’s Sonambient sculptures—which structurally emulate the forms of wheat fields, willow trees, dandelions and cattails—attest to his lifelong appreciation of music (he counted Vivaldi and Mozart among his favorite composers). However, the decision to incorporate sound into his sculptural work came about in a rather serendipidous manner. In his studio in Bally, Pennsylvania, Bertoia accidentally struck a metal rod while bending it and was intrigued by the sound. He began experimenting with the different tonalities associated with brass, bronze, beryllium, stainless steel and nickel alloys. Noting that musical instruments have secondary aesthetic properties to their primary, functional designs, Bertoia reversed this heirarchy, so that the sonorific qualities are secondary to the aesthetic. Like the wind responsible for the rustling of leaves, distortions caused by a breeze or a draft create gentle chime-like sounds in Bertoia's Sonambient sculptures. He later worked with recording artists to capture the sculptures' sounds in a barnyard setting, and released as a collection of eleven vinyl LP records.

After an illustrious career in which he produced over fifty public works, Bertoia died of lung cancer in 1978, at the age of 63. His wife, Brigitta Valentiner, died in 2007, aged 87. Today, his estate is managed by three of his great grandchildren, including Celia Bertoia. For more information on the life and work of Harry Bertoia, visit the Harry Bertoia Foundation.

View clips from Glenn Adamson's lecture, "Learning from Bertoia" below:

Watch the Full Video

Watch an Excerpt