This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of The Noguchi Museum in Long Island City, Queens, New York dedicated to the life and work of the Japanese-American sculptor. The celebration includes three major exhibitions—Museum of Stones, Tom Sachs: Tea Ceremony and Isamu Noguchi at Brooklyn Botanic Garden—and a forthcoming monograph titled The Noguchi Museum: A Portrait, which will be the first publication to chronicle the museum's life, history and design.

Dakin Hart is the Senior Curator at The Noguchi Museum. He came to the museum after working at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Montalvo Arts Center, the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas and the Gagosian Gallery in New York. Hart sat down with Knoll to discuss the museum's anniversary celebration and the enduring legacy of Isamu Noguchi.

Courtyard of The Noguchi Museum. Image courtesy of The Noguchi Museum.

“The panoply of things Noguchi means has never been more relevant than now.”

—Dakin Hart

KNOLL INSPIRATION: This year marks the 30th anniversary of The Noguchi Museum, which was founded in 1985. How is the foundation celebrating this milestone?

Dakin Hart: We’ve created a group of exhibitions to show some of the range and complexity of Noguchi and his practice. The goal this year is not to further oversimplify Noguchi, not to create an alternative cliché, like his being an ambassador between East and West—which is hugely important and very true, but has been overworked.

At the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, we're exhibiting Noguchi in a natural setting, giving his sculpture what it wants: a rich and expansive environment in which to operate. The metaphor we use is one that Noguchi himself provided, that outdoor sculpture should be judged by the same standards that a landscape gardener uses to judge the placement of a tree or a rock: does it substantially enhance or add to the natural setting? The purpose of partnering with the Brooklyn Botanic Garden is to test that out by placing these sculptures in what we think of as Noguchi’s most natural habitat.

Here at The Noguchi Museum, we’re doing an exhibition called Museum of Stones, which I think of as a biblical exegesis of Noguchi’s relationship to stone, which is incredibly complex. It’s literary, it’s linguistic, it’s scientific, it’s historical, as well as material and artistic.

We’re also using the anniversary as an excuse to, for the first time, bring contemporary art into the museum in a major way—both on the second floor, where we have a special exhibition space, and on the lower level, the historic Noguchi installation. That’s our big project for the fall.

The panoply of things Noguchi means has never been more relevant than now: his multiculturalism, his cosmopolitanism, his interest in the Anthropocene and the ecology of our planet. He was no wide-eyed idealist, Noguchi was much more of a conceptual artist than people give him credit for. So the idea behind all of this is to open up and dig in.

Chabako (Tea Utensils) by Tom Sachs, 2015. Image courtesy of Tom Sachs.

In his lifetime, Noguchi befriended and collaborated with artists of various disciplines: Buckminster Fuller (architecture), Martha Graham (dance), Kitaoji Rosanjin (pottery), John Cage (music) and Arshille Gorky (painting). Given the close relationships Noguchi forged with such individuals, can you explain the rationale behind choosing Tom Sachs to be the first artist, other than Noguchi, exhibited at The Noguchi Museum?

There is one major reason: The hope here is to look toward the future, so we wanted a living artist. The thing about Tom is that he and Noguchi share something in common. In his time, Noguchi said he was trying to "pursue the true development of an old tradition." And he did that by electrifying an Akari lamp, making Japanese ceramics non-functional, hybridizing the Japanese garden—all of which were hugely controversial and got him in all sorts of trouble. He was trying to adapt real craft traditions for a new age and a new society.

That’s what Tom is about. Tom is interested in taking craft traditions and trying to make them contemporary by developing them within a vocabulary and a set of interests that make sense to him. Tom’s space project may be fictional—and it is full of fun and mischief—but at the end of the day it's true, it's sincere, it’s emotionally honest and committed. It's on the level of craft that he and Noguchi connect.

They also share a distain for the balkanization of creativity, the idea that the instincts that serve table making should be separate from sculpture making because of some formal hierarchy. They both want to break down those walls. Tom is never happier than when he’s making objects that scamper over the boundaries between furniture, object and sculpture.

“The essence of sculpture is, for me, the perception of space, the continuum of our existence.”

—Isamu Noguchi

Installation view of Area 11 at The Noguchi Museum. Image courtesy of The Noguchi Museum.

In some of the current galleries, the museum has restaged notable exhibitions of Noguchi’s work over the years, demonstrating his holistic approach to an exhibition’s environment. What is the relationship between Noguchi’s works and the spaces he designed to present them?

That question frames his entire career and it’s a very complicated one. He spent his whole life trying to answer it, not answer it, but explore it. In 1996, the title of his Venice Biennale exhibition was “What is sculpture?” He was told not to put lamps in the show, so he developed an entire line of lamps to exhibit. The center piece was a twelve-foot-tall usable marble slide, so the show was about breaking down the barriers between sculpture making and living.

He wrote a really interesting article in Art In America in 1964 and there’s an insightful passage where he talks about the Chase Manhattan Sunken Garden and why he calls it a garden and not a courtyard—because it really is a courtyard, conventionally speaking. In a garden, everything is the sculpture, the space is the sculpture; a courtyard is a space populated by things. In a courtyard, the “thinginess” of the objects in it becomes paramount, whereas in a garden, it’s the combination of all those things working together that creates a sculpted space.

In terms of the exhibitions themselves, our goal in re-presenting them is to preserve a sense of the whole, which is something I think the museum does best.

Installation view of Area 7 at The Noguchi Museum. Image courtesy of The Noguchi Museum.

Noguchi wrote that: “The essence of sculpture is, for me, the perception of space, the continuum of our existence. All dimensions are but measures of it […] volume, line, point, shape, distance, proportion […] these are the essences of sculpture and as our concepts of them change so must our sculpture change.” What conceptual changes are cataloged by Noguchi’s artwork? Furthermore, since Noguchi’s death, has our “perception of space” changed?

On aggregate, sculpture has advanced in leaps and bounds. In the 1960s, Noguchi had to fight to get his dealers to show work in anything other than bronze and marble. When they did show something beyond those traditional materials, they couldn’t sell it. There was a huge resistance to the idea of sculpture divorced from its material considerations. Now, sculpture is everything, and maybe more synonymous with art than painting, which is a radical reversal. I think Noguchi is partially responsible for that.

But I’m going to answer you by way of another quotation. It’s from a very strange source, it’s from Queen magazine and it hasn’t really been anthologized. Queen magazine did a special issue on Japan in 1970, right after the moon landing. Noguchi was obsessed with space exploration, and what he posits at the end of this article is that conceptually, we’ve outgrown the earth. What he's driving at is that the moon landing has irredeemably shifted the consciousness of mankind, so that it is no longer possible to operate in scale with nature as defined by planet earth. It's hard to remember, but no one had seen that big blue marble photograph of the planet until 1969. Noguchi's definition of sculpture meant always looking for the horizon.

“Among his many talents, Noguchi was adept at finding mentors, collaborators, friends and creative partners.”

—Dakin Hart

Isamu Noguchi in Romania with The Kiss by Constantin Brancusi, 1981. Image courtesy of The Noguchi Museum.

Noguchi studied under two notable sculptors: Constantin Brancusi and John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum—the sculptor behind Mount Rushmore. The former was a lifetime friend and mentor; the latter encouraged him to quit sculpture entirely. In what way did these two teachers, for better or for worse, impact Noguchi’s artistic development?

One of the things that Noguchi was fantastic at was working on a micro- and macro-scale. He had the ambition of Borglum, “the Mountain Shaper”—Michalangelo wanted to carve out an entire mountain, Borglum actually did it. So, the scale and scope of Borglum is there while his attention to detail is indebted to Brancusi. Among his many talents, Noguchi was adept at finding mentors, collaborators, friends and creative partners. He absorbed not their technique, not their formal interests, but the scope of their intentions and synthesized those into something else for himself.

Three-legged Cylinder Lamp, 1944 by Isamu Noguchi for Knoll. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

Noguchi was very vocal in his opposition to art as a discipline removed from everyday life. In the essay What’s the matter with sculpture? the first problem Noguchi iterated was “[sculpture’s] subject matter, whether imaginative or realistic, [having] no relation to life of today.” Through his own work, spanning lamps, sculptures and tables, Noguchi endeavored to “inject [an artist’s] knowledge of form and matter into the everyday, usable designs of industry and commerce.” How does the museum represent Noguchi’s oeuvre as continuously engaged with the world?

We are the museum, but we are also the foundation. Noguchi’s legacy and reputation is the mission. The museum is one of the ways that we’re able to pursue that, but it is not all we have at our disposal.

This place is a flag in the ground, it’s a milestone, a point of reference. Noguchi wanted to make something that would carry a certain set of values, and it’s relative isolation from Manhattan serves as an important buffer. He described it as "an oasis on the edge of a black hole." That gives you a sense of from his point of view.

He put no restrictions on what we could do. If you look at places like the Barnes Foundation, or the Frick Collection, even the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, they're all restricted. He didn’t do that because he was always "looking beyond the false horizon of the museum pedestal." That defines so much of his career, trying to escape the white-box of the museum, the collector’s living room. He knew that for the things that he cared about to continue to be relevant, they would have to be updated and translated by dedicated stewards from generation to generation.

“The Cyclone™ Table is such a great example of the way that he innovated, which is through a twist of perspective based on a sculptural idea: how to suspend mass.”

—Dakin Hart

Cyclone™ Dining Table and Cyclone™ Side Table, 1957 by Isamu Noguchi for Knoll. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

Noguchi latched onto opportunities to partner with companies like Zenith, Steuben Glassworks and Knoll to design commercial products intended for mass-production. Are these industrial designs—including the Cyclone™ Dining Table and Cyclone™ Side Table—related to his primary sculptural work?

Noguchi, maybe better than anyone else in the 20th century, sits on that nexus, that inflection point between art and design. There are many people trying to figure out how he did it and the problems he encountered on both sides, but ultimately it comes down to framing: He was presented one way in one field and another way in the other. Why is he top-five designer but not a top-five sculptor or artist, in the opinion of those who would make such lists? It’s hard to explain.

The traditional art historical narrative is one where of course great art can lead to great design, but it can never go the other way. With Noguchi, it goes the other way all the time. A lot of his best sculpture ideas came out of furniture and other kinds of object design.

Bertoia Side Chair and Cyclone™ Dining Table. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

When Hans Knoll first approached Noguchi about the prospect of a collaboration, the company was experiencing success following the 1952 debut of the Bertoia Collection. While Noguchi envisaged his Cyclone™ designs as being made out of plastic, “[Hans] wanted them in some sort of wire, à la Bertoia”. How do the finalized designs compare to Noguchi’s works in other materials—basalt, granite, balsawood, bronze and aluminum?

While Noguchi never met a material he wasn’t interested in, he did not develop a good relationship with plastic. Since the time he started working with the material, he had a very hard time finding its essence, its unique and exploitable characteristics. He liked to put materials through their paces, to see what they could do.

The Cyclone™ Dining Table, on the other hand, is such a great example of the way that he innovated, through a twist of perspective. To turn a table into a bicycle wheel, that is such a brilliant idea. It creates a table that looks amazing and is conceptually fantastic. Formally, the base and the top are wired together, strung together. The top doesn’t rest on or derive support from the base. Instead, it is latched to the base, creating a suspended table. That shift in perspective is based on one of his sculptural ideas: how to suspend mass.

“It’s not about answers, it’s about questions. It’s not about tidying up, it’s about messing up. It’s not about simplifying, it’s about complicating. That’s what we’re trying to do.”

—Dakin Hart

The sculpture garden of The Noguchi Museum. Image courtesy of The Noguchi Museum.

In terms of his intellect, Noguchi was truly cosmopolitan—drawing on ideas from England, France, Italy, Indonesia, China, Japan and the United States. Yet, as a Japanese-American, Noguchi maintained two studios, one in Queens, New York and one in Shikoku, Japan. To what extend does the museum aim to transcend its Long Island City location in representing Noguchi’s art, influence and cultural heritage?

It’s what we’re trying to do with these three big installations. The goal is to show the multifaceted nature of Noguchi. That’s why we wanted to do more than the one exhibition, because if you only do one show on Noguchi, in some sense you're falsifying his legacy. There is nothing wrong with exploring facets of an artist's career, but Noguchi, in particular, has become so encumbered by clichés. So, we’re trying showcase his work in a new light. His interest was in civilization, the planet and the universe. For him, every sculpture was an attempt to create "a universe in grain of sand," to quote the great William Blake poem.

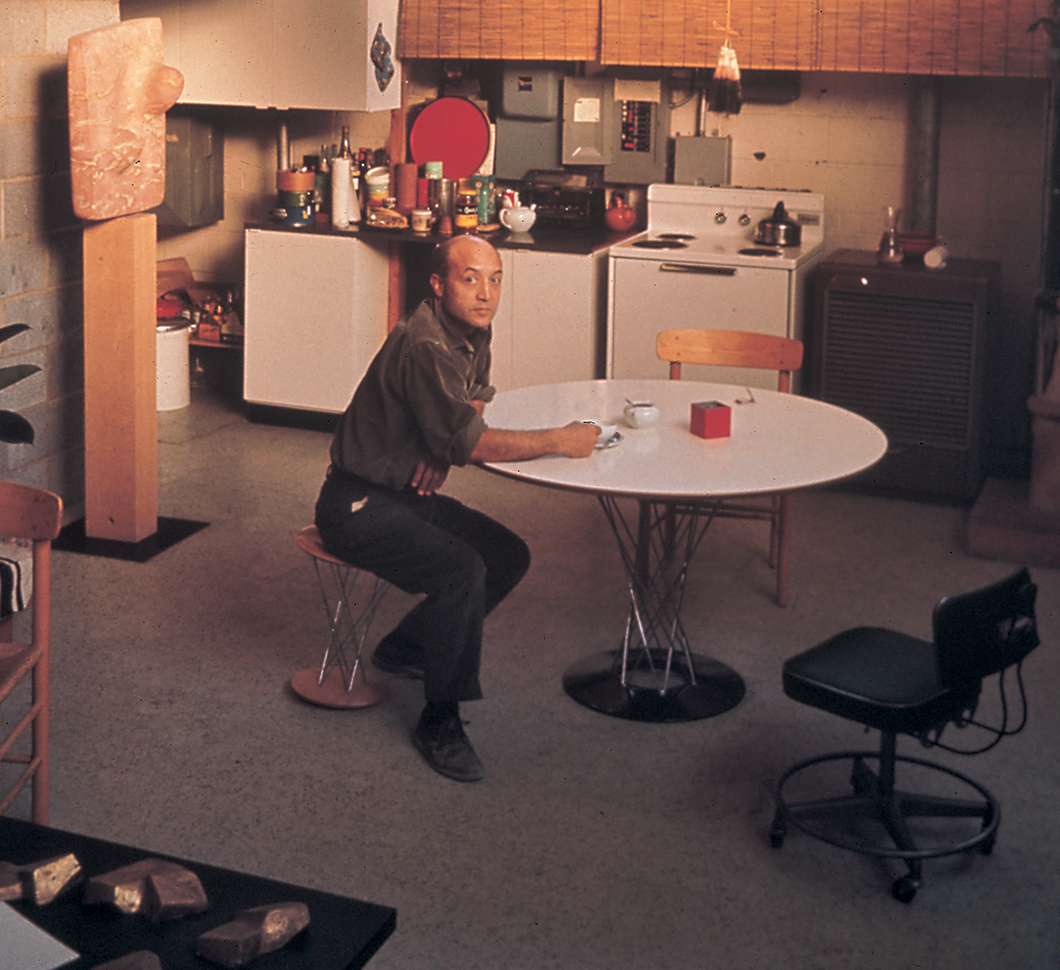

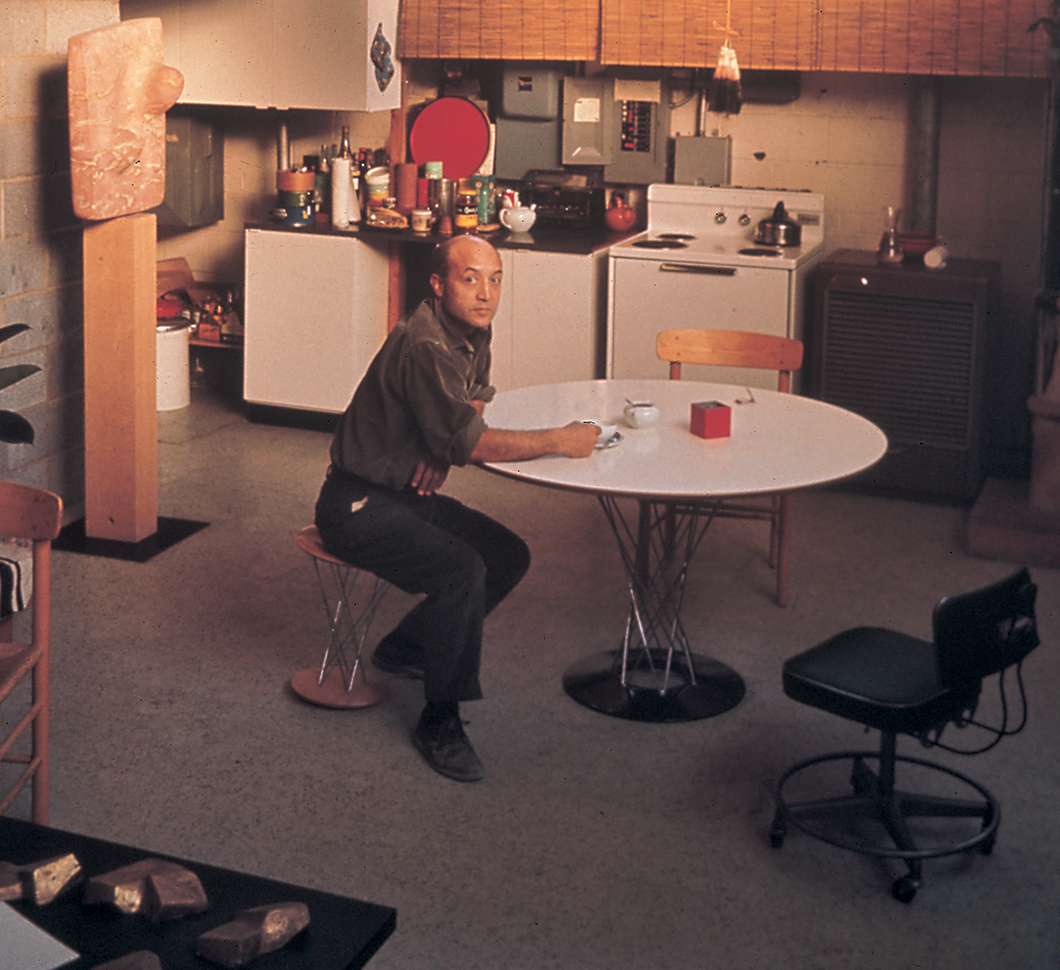

Cyclone™ Dining Table and Cyclone™ Side Table at the designer's home. Photograph from the Knoll Archive.

In closing, do you have any thoughts on the enduring legacy of Noguchi today?

It’s not about answers, it’s about questions. It’s not about tidying up, it’s about messing up. It’s not about simplifying, it’s about complicating. That’s what we’re trying to do. We’re lucky in that we don't have to perpetuate a living artist’s legacy. Instead, we get to explode and explore Noguchi's work in many different ways.

All images are courtesy of The Noguchi Museum unless otherwise noted.