The influence of fashion is a legacy at KnollTextiles, and has been since the very beginning, when Florence Knoll introduced upholstery that was inspired by men’s suiting. Dorothy Cosonas, Creative Director at KnollTextiles since 2005, studied fine arts and textiles at the Fashion Institute of Technology, and she is deeply inspired by fashion. In November, KnollTextiles will launch a collaboration with a fashion designer for the Luxe Collection (the details are yet to be disclosed).

In the mean time, we sat with her to talk about Arezzo, the latest Luxe upholstery that was inspired by the late Alexander McQueen’s No. 13 dress, and to hear about her perspective on designing Modern.

KNOLL INSPIRATION: We’re here in New York City. Do you have a favorite space to go to for inspiration?

DOROTHY COSONAS: New York City is much too big for just one favorite. Each day I walk down the street there’s something to see with fresh eyes, even on a well-worn path. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is one that has such a depth of knowledge from the dawn of civilization to today that you can never take it all in; that’s why I go back time and time again. The MoMA [Museum of Modern Art] as a temple to modernism can’t disappoint. And Bryant Park is a little piece of Paris near my house that often doesn’t get its due. Inspiration as a designer comes from keeping your eyes open.

We know that your design for the upholstery Arezzo, from KnollLuxe’s most recent collection, was inspired by the No. 13 dress at the Alexander McQueen retrospective at the Met, back in 2011. There is a video from one of McQueen’s runway shows, in which two robotic arms spray paint a white dress while it is being worn by the model Shalom Harlow. What excited you about the dress, and how did you see it becoming upholstery?

Oh yes, the No. 13 Dress. The concept was to use these machines with the human model to create something beautiful, with amazing color, which was very organic. The process and the result intrigued me. What we tried to mimic was that idea of the human hand and the machine together.

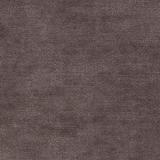

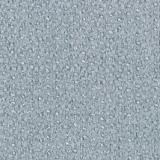

The Arezzo upholstery from KnollLuxe, in Aqua (left) and Squid Ink (right).

“I think if you don't get nervous, then you are resting on your laurels.”

—Dorothy Cosonas

What is that process? How is Arezzo made?

The greige goods [an industry term for a plain fabric before it has been dyed] are first laid out flat. Then a mill-worker scrunches the greige goods by hand, creating highs and lows in the fabric. The scrunched fabric moves by conveyer belt to the next station, where high-pressure jets randomly hit the fabric with four colorways according to the selected palettes, before the fabric moves on to the customary processes of brushing, cleaning and washing. The trick was finding this mill that could be both the man and the machine. And the result is unique. No two yards are alike.

Arezzo is produced through a combination of hand techniques and machine processes.

How did you develop the four colors, Dolce, Aqua, Truffle and Squid Ink?

Color is a very personal idea. I always say to students: Color trumps all! A great pattern badly colored will never sell. People have a gut reaction to color that supercedes everything. For Arezzo, it was about finding the right relationships between tone and value. Does the value of this blue relate to this purple, to this grey? That’s the design process.

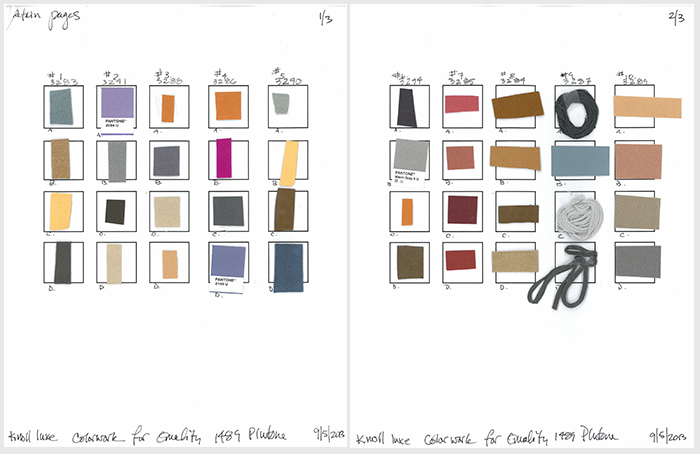

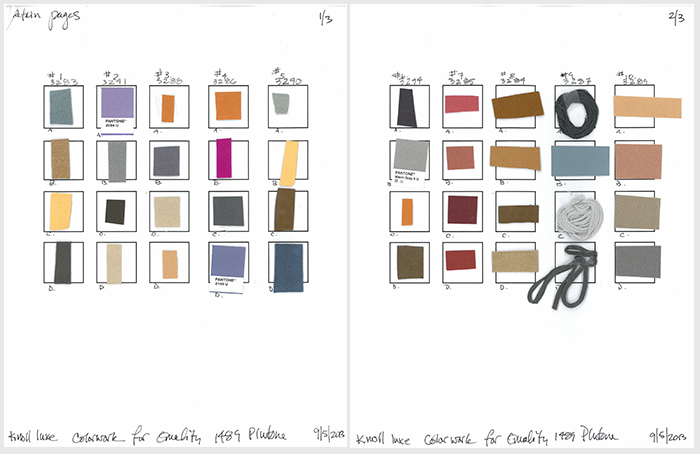

Some of the color work submitted to the mill to create strike-offs for Arezzo.

Besides McQueen, were there any other inspirations that came into play as you designed Arezzo—its colors, material, patterning?

No, the look and the process were the drivers. Most commercial textiles today are produced in a very modern way. There are some exceptions—we have some hand-made fabrics from India, for example, which are beautifully made—but for the most part, KnollTextiles is very technologically-driven in production. So here, because it was Luxe, we were able to do something we couldn’t do in our other lines.

KnollLuxe's upholstery Jaipur is handmade in India.

You are also known for initiating highly successful collaborations with young fashion designers—Rodarte, Proenza Schouler, SUNO. How do you convince designers who usually design clothes for people’s bodies to design clothes, so to speak, for rooms?

With SUNO, Proenza Schouler and Rodarte, I was already in love with their fashion work, so it was not a stretch for me to see them working with Knoll. The challenge was getting them to see themselves making a textile, and to find the time to work with us. I’m looking for designers with a unique sense of texture, color and pattern, who share a modern aesthetic. With SUNO, Proenza and Rodarte, each had a unique vision of their own work that was correct for KnollTextiles.

Textile design must be exciting, because once it leaves the hands of the designer, so much can happen to it that you don’t expect. It goes out and lives somewhere with other things that may influence it. When you design a fabric like Arezzo, where do you imagine it living afterwards?

I don’t imagine it in a certain space, so much as I envision it on a particular piece of furniture. (That’s for the specifier to do.) Even though I’ve been doing this for a long time, I still get excited when I see a fabric installed somewhere that I didn’t expect. I still can say, ‘Wow, look at that!’ And I still get nervous when I work and introduce something. I’m very glad about that. I think if you don’t get nervous, then you are resting on your laurels, and you start to design by auto-pilot, which isn’t good. I’ll ask myself questions. ‘Does this look nice?’ ‘What would Florence [Knoll] think of that?’ You ask, ‘Is this at a level that allows it to live in history and up to our proud tradition?’

As we end, let’s go back to the beginning. What’s your earliest design memory?

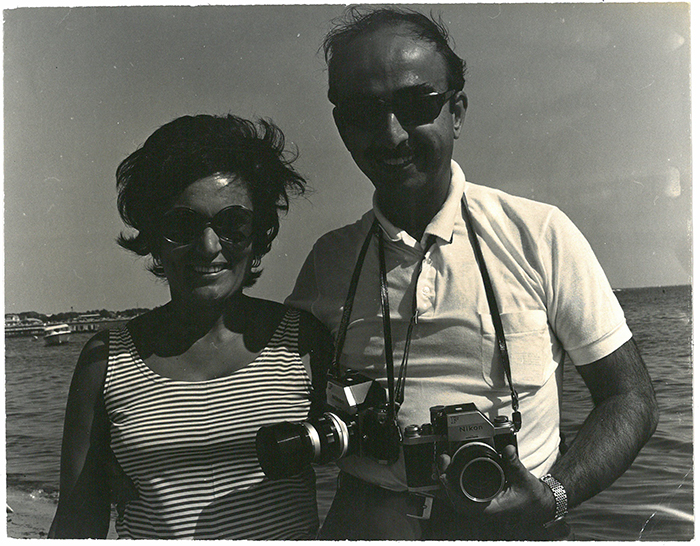

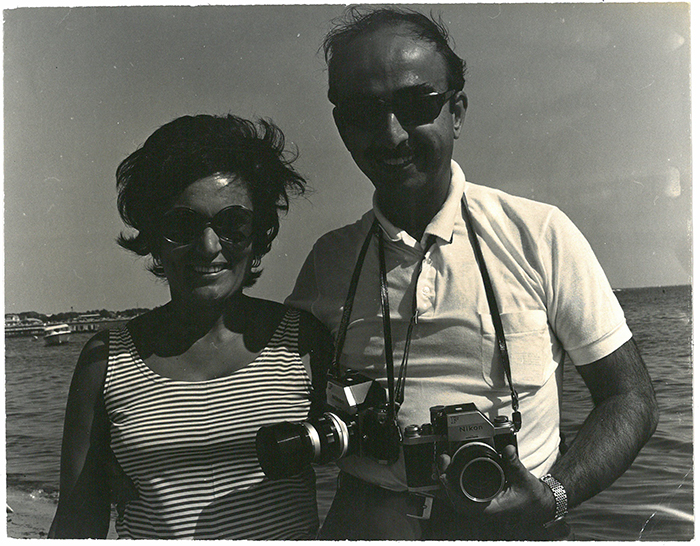

My father was an engineer, but his real passion was photography. He had a darkroom in our basement, and he’d call me down, “Help me develop these photos!” So throughout my early teens, I’d help him. It was amazing, how instantly the picture would appear out of a blank sheet. It was a fascinating thing, although I complained about it then. And while I didn’t know it at the time, I think he planted this notion of the design process. It starts with an idea—what you see in the camera—and by the end, you have the final result, the physical picture. But you have to be patient. Each step counts, each step is important to get to that final goal. And that’s what I still know about design.

Dorothy Cosonas' parents in Greece in the 1970s. Photograph courtesy of Dorothy Cosonas.

All images are courtesy of KnollTextiles, unless noted.