Industry-wide consolidation, regulatory demands and economic pressures have further stressed a healthcare industry already struggling to rein in spiraling costs while improving outcomes. Technological innovation and medical advancements add further complexity.

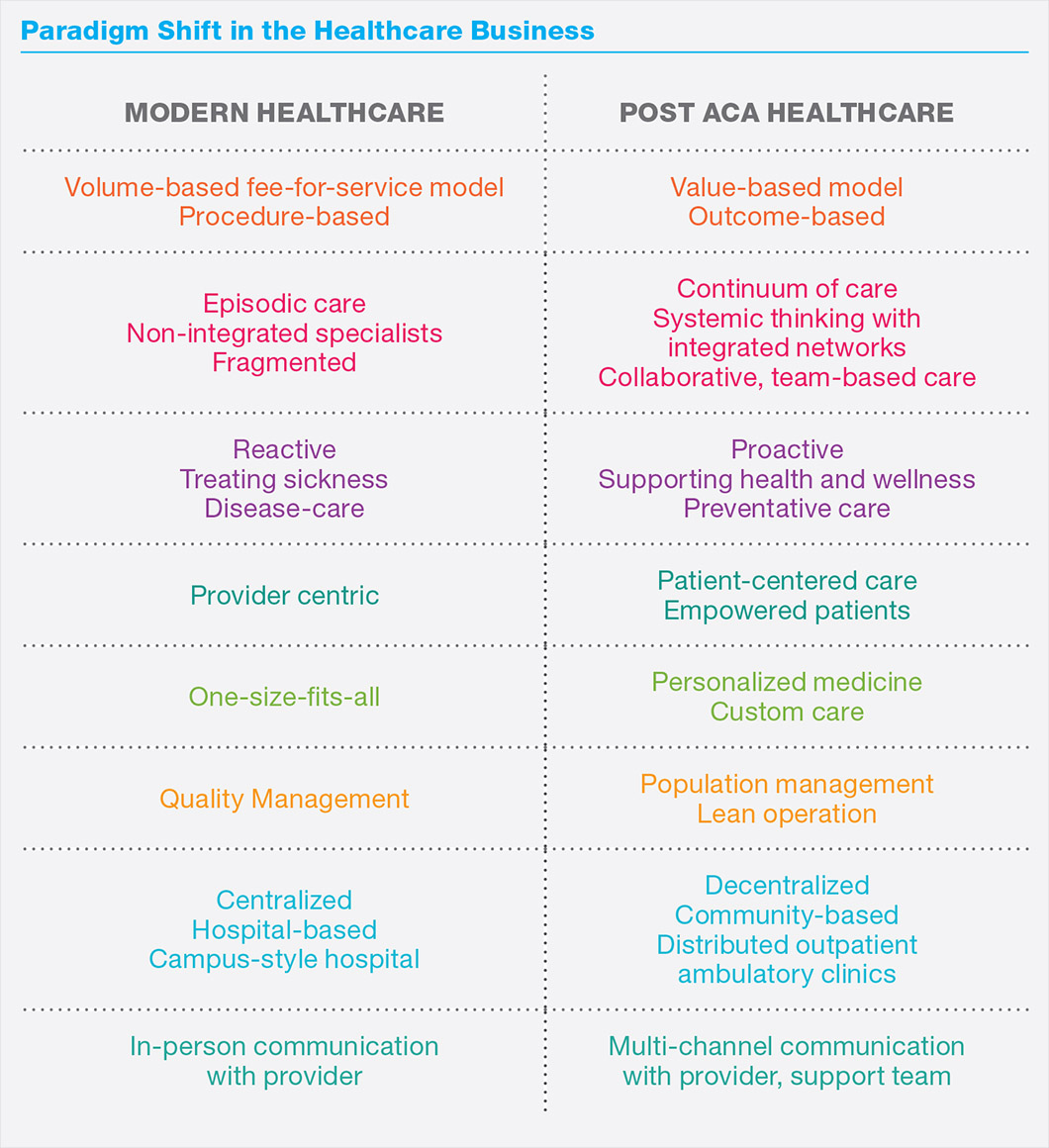

Healthcare reform continues to reshape the industry. While the status of the Affordable Care Act may change, its intent—to provide care for all Americans while reducing healthcare costs through adequate preventive care—and accompanying mandates have spurred new standards of healthcare delivery that will live on.

A shift from a fee-for-service model to one that bases reimbursement on value is driving fundamental changes in the industry, one in which providers are now rewarded for outcomes and patients take greater responsibility for their care.

Seeking to attract healthy patients as well as the sick, providers strive to deliver a continuum of care to a population that is growing in size and increasing in age. Patients, empowered with choice and well-versed in comparison shopping, seek value and convenience from their healthcare providers.

A more patient-centered, family-focused perspective has emerged, inspiring new models of care delivery. Growing numbers of free-standing ambulatory clinics provide convenient alternatives to traditional hospitals while meeting articulated population health goals.

These trends have far-reaching impact and influence on the design of healthcare environments.

Knoll studied the changing healthcare ecosystem, including speaking with industry observers and experts across the country, to identify the most significant trends driving planning for healthcare environments today. We then conducted one-on-one interviews with more than two dozen physicians and medical professionals, architects, designers and end users to learn about new care delivery models and designs for the changing healthcare landscape.

This brief is the culmination of our study and suggests planning and design strategies to support new models for today’s built environment that also adapt to future standards of care delivery.

Drivers, Culture + Characteristics

While healthcare reform has impacted the industry on numerous levels, modern healthcare environments are also strongly influenced by macro trends including shifting demographics and new technology, as well as the industry’s unique culture and an operations-heavy business model that runs around the clock.

Scale Matters

Mergers, acquisitions and consolidations have been rampant in the healthcare industry, hitting a record high in 2015 and showing little sign of abating. Banding together to build a mega-brand healthcare system can create the scale needed to survive in a competitive environment, as well as boost gains in market share, improve operating efficiency, streamline care delivery and increase profitability.

Slow-to-Change Culture

As a behemoth industry that accounts for 17% of U.S. GDP, change in the healthcare industry comes slowly. So, despite a shifting political climate and leadership, policy and program changes take years to develop and roll out.

Oftentimes the biggest challenge to hospital construction is not financial or technical, but cultural, noted Debajyoti Pati, Professor at Texas Tech University. As consensus building organizations, it can be very hard to get leadership and planning team members moving in the same direction. Moreover, lengthy construction schedules tend to add complexity as leadership regimes often transition during a building’s protracted construction phase, which averages 5 to 6 years and up to 10 for federal government facilities.

Even when new models are implemented, change is sometimes slow or met with resistance, according to Dr. Pati, who has observed hospitals maintaining a centralized mode of operations, for example, even after they are re-designed as decentralized inpatient facilities.

Shifting Demographics

As modern medicine extends lifespans, the Baby Boomer population is putting additional demands on the healthcare system as they age. Often called the silver tsunami, this population segment will increase needs for hospice and end-of-life care as well as management of chronic and dementia-related conditions like Alzheimer’s.

Another large and growing population segment is millennials who, as they begin families, will utilize more medical services than they have in the past.

Impact of the Affordable Care Act

Signed into law in 2010 and rolled out in 2014, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA or “Obamacare”) went beyond transforming coverage and care. It opened up a broader dialogue about the basic mission of public health in a nation with universal coverage that continues to this day. With a focus on value and outcomes, rather than volume, it altered the healthcare cost structure and increased the demand for greater accountability.

Expanding insurance coverage and access added 20 million Americans to the 300 million already covered. Though the particulars may be undefined, the new government administration has pledged universal coverage for all Americans, potentially expanding the ranks even further. A larger patient base is likely to trigger a need for more facilities, as well as put greater stress on an already stretched healthcare workforce.

New Approaches in Healthcare Delivery

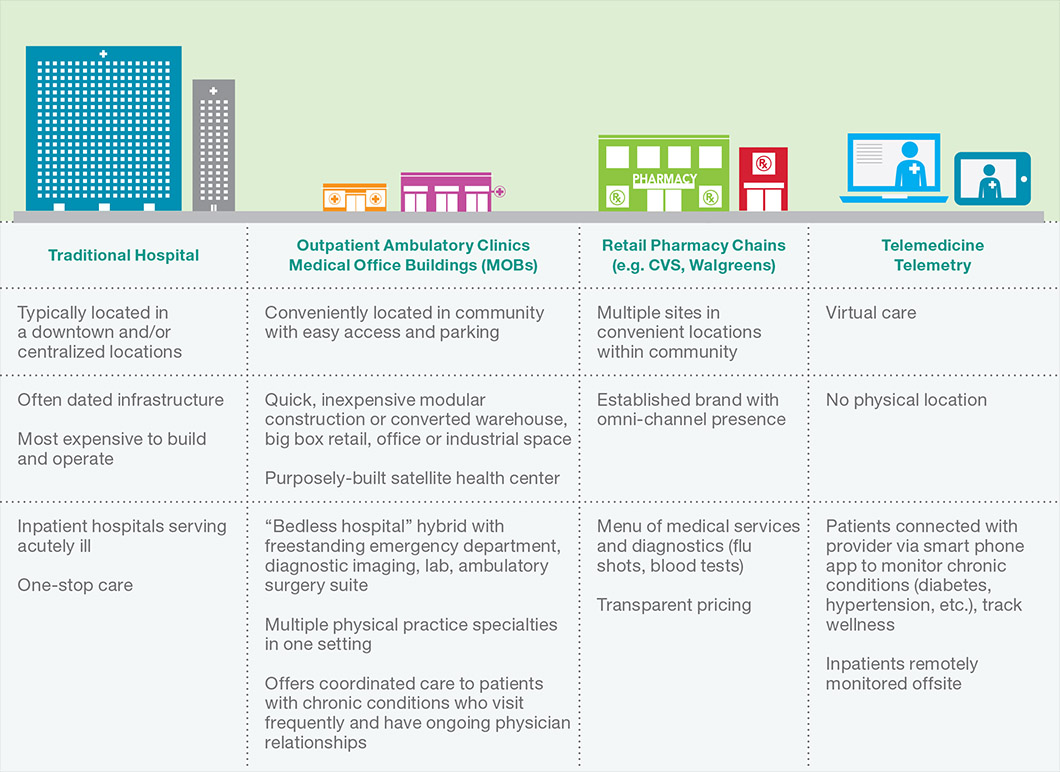

The centralized, campus-based healthcare economic model that was built around inpatients, surgeries and procedures is rapidly being diluted by lower cost methods of delivery. In large part due to the ACA and its emphasis on population health, but also due to a focus on operational efficiency, changing technology and new models of care delivery, services are moving outside the hospital to new ambulatory outpatient clinics and community health centers.

Triple Aim Concept. One framework based on a patient-centered approach is the Triple Aim concept developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). Designed to optimize health system performance using a holistic approach with three dimensions, it is considered an extremely ambitious strategy to galvanize system-wide health improvement. Successful implementation of such large-scale changes will likely result in fundamentally new systems that contribute to the overall health of populations and reduce the cost to society.

The premise behind Triple Aim is that new design solutions must address three key dimensions concurrently:

1. Improve the patient experience of care, including quality and satisfaction based on six dimensions (safe, effective, patientcentered, timely, efficient, equitable)

2. Improve the health of populations, requiring the engagement of partners across the community to address the broader determinants of health

3. Reduce the cost of healthcare on a per capita basis via cost control and improve the return on resources invested

The IHI believes that to improve all levels of the system requires harnessing a range of community determinants of health, empowering individuals and families, substantially broadening the role and impact of primary care and other community-based services, and assuring a seamless journey through a lifelong continuum of care.

Since healthcare itself comprises just 10% of multiple determinants of health, political changes are not expected to change a focus on population health, according to Carol Beasely, IHI senior vice president. “The fact is that healthcare is part of a system of health, and includes other elements such as behavioral patterns, genetic predisposition, social circumstances and environmental exposure,” she explained.

Focus On Population Health. Fundamental changes to care delivery—particularly at the primary care level—have emerged to support population health and its multi-pronged focus on proactively preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through organized efforts and informed collective choices. “Even before the ACA, we knew to be successful in the long run required managing three aspects of the system,” IHI’s Beasely explained. “We had to provide great care. We had to be concerned about populations and we had to think about the total cost,” she said.

Hospitals and health systems are now rewarded for offering high-quality care, reducing unnecessary hospitalizations and preventing readmissions. Patient health, including chronic diseases or disabilities, is managed through a combination of behavior change and evidence-based medicine focused both on prevention and treatment of injury and disease.

Collaborative Team Care Model. Team care is a concept with new treatment modalities designed to improve the patient experience. It has been proven to increase the number of patients seen per day, improve satisfaction levels of patients and staff and increase gross patient revenue. With its emphasis on collaboration across disciplines, it is also designed to reduce the “siloed” nature prevalent in much of healthcare to one more in line with the team approach being taught in medical school and already in place in many corporate work environments.

With its multi-disciplinary approach, team care allows for greater interaction between patients and providers as well as between providers themselves through more efficient use of time, space and resources. Instead of the standard clinical model with disconnected individual areas—typically private offices for physicians separated from nursing station and exam rooms—work and social interactions happen in a range of flexible multi-function workspaces. All providers—physicians, nurses, physician’s assistants, therapists and social workers—work side by side in close proximity providing patient care and sharing information.

The expectation is that compliance will be higher if patients depart with care plans from all members of the provider team and that investment of effort will keep the patient from returning with exacerbated conditions, thus improving outcomes and lowering readmissions.

Lean Thinking. Based on the model developed by Toyota, lean thinking identifies and eliminates waste in any activity performed within a facility by focusing on process improvement and change management. The concept of the most efficient use of staff, resources and technology to provide the highest level of service to the consumer is being adopted across the healthcare industry, ranging from daily operations to how to plan the physical environment.

When lean management processes are successfully applied in a clinic setting, patients benefit from more time from clinicians, greater safety, less delay in receiving care and more timely results and treatments. Staff benefit by having fewer steps, less work and greater opportunities to care for patients.

Outpatient Care. Outpatient facilities, such as freestanding emergency and urgent care clinics, ambulatory care centers and medical office buildings, typically under the banner of a mega-brand healthcare institution, bring outpatient services closer to patients in their communities to offer more responsive care while reducing demand for more expensive acute care services.

Clinic designs center on patient flow so providers can serve patients quickly and efficiently. They provide basic services and procedures such as primary, specialty and/ or urgent care; imaging and lab work; and/ or rehabilitation. Patients enjoy convenient access, good parking, extended hours and adjacent community and retail destinations.

Situated in suburban or outlying rural locations, outpatient facilities often serve as a “spoke” to a hospital’s more centralized “hub” or primary location. With a relatively small investment needed, smaller freestanding facilities are an appealing way for hospitals to grow when space is not available at the current facility, or to test expansion into a new community in hopes of growing the patient base. Additionally, less complex design and construction expedites speed to market, allowing institutions to get a jump on the competition and capture market share.

Healthcare institutions are also finding opportunities to reach consumers where they shop and live by repurposing underutilized real estate. Large warehouses, industrial spaces and commercial buildings that formerly housed “big box” retailers are seeing a second life as newly minted outpatient facilities.

Patient Education. Incentives from the ACA may have inspired the establishment of employer wellness programs in some companies, but a proactive focus on healthy living has become the norm for any entity seeking to reduce medical costs. Thus healthcare institutions are prioritizing delivering education to patients and responsible family members through multiple channels, supporting efforts to keep patients out of the hospital.

Healthcare Environment Solutions and Strategies

Producing a superior patient experience depends on three factors coming together: caring staff (people), patient-centered operations (process) and well-designed facilities (place). As the industry transitions to a patient-centered model focused on achieving good outcomes, a positive experience is a key metric, maximizing reimbursement as well as attracting patients.

The built environment plays an integral role in supporting these new models of care delivery. Environments must respond to healthcare’s new paradigm with flexible, multi-purpose, technology-enabled spaces that meet today’s standards of patient care, family involvement and multi-disciplinary care teams with increased patient satisfaction, caregiver productivity and throughput. Our research suggests five strategies to successfully create such spaces.

1. Enhance the Patient Experience to Promote Healing and Comfort.

A holistic approach that engages multiple senses and addresses emotional and spiritual needs can reinforce healing efforts on a deeper scale.

Planning Strategies

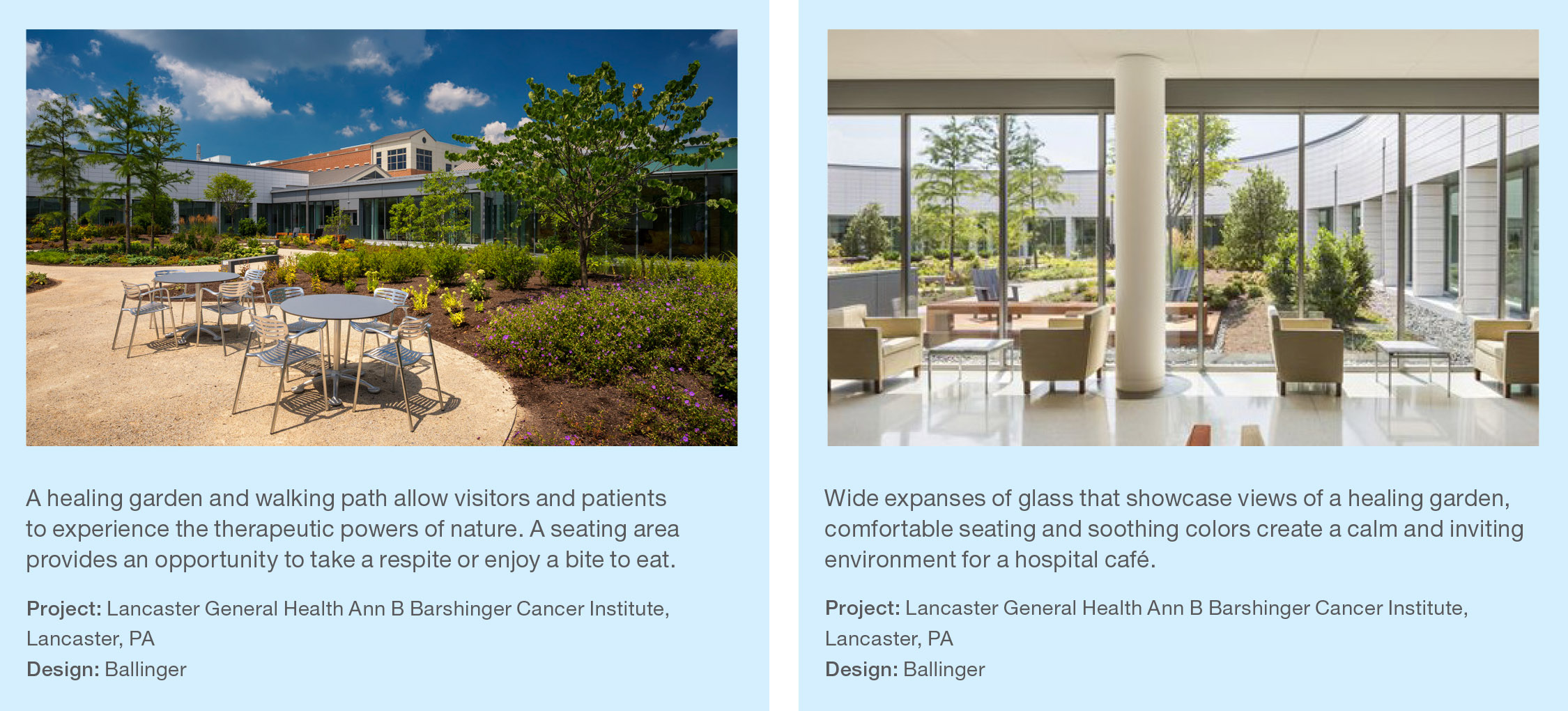

- Connections to nature and opportunities for reflection. Warm, inviting spaces that provide connections to nature and inspire mind, body and soul have far-reaching healing effects. Bringing nature into a room by providing views of the local landscape has been proven to shorten healing time, lower stress and decrease the need for pain medication. Adjacent green spaces, nature paths, outdoor terraces or rooftop gardens allow patients and families to engage with the outdoors and connect to nature.

- Natural light and views. Daylight and healthful sleep can be more important than medication in advancing healing. Upon completion of its new LEED-certified facility in Madison, Wisconsin, UW Health relocated a large number of orthopedic patients from its existing facility. Average length of stay of patients in the new UW Health at The American Center facility, which is bathed in generous natural light, was reduced by one full day. Good lighting can also convey a higher perception of cleanliness, an important factor on HCAHPS scores.

- Design that distracts and engages. A hospital visit is typically an anxietyprovoking experience for both patient and accompanying family member. Creative design elements in the built environment allow patients and their families to focus on something else and accelerate the healing process.

- In pediatric inpatient facilities, where patients frequently return multiple times for treatment, making the experiencing interesting and engaging is particularly critical. Designer Anita Rossen of ZGF strategically used an animal-themed motif with colorful, large-scale graphics for wayfinding in Seattle Children’s Hospital. Graphic landmarks also simplify wayfinding, further lowering stress levels.

- At the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Specialty Care Center, designers conducted extensive research from the patient’s perspective to learn how children interact with and perceive healthcare spaces and how the design of the specialty care center could be leveraged in healing ways.

- When research revealed a particularly high level of sophistication in children’s cognitive abilities, the team was inspired to create dynamic environments that engage multiple age groups, rather than a simplistic, static visual space.

- “What we really wanted to do was to advance the environment as a therapeutic tool and to make sure that when there was a distraction, it was in a location that could benefit the patient the most,” explained designer Jocelyn Stroupe of Cannon Design.

- As a result, a highly engrossing design is based on a theme of imagination and discovery, focusing on opportunities to play, socialize, fantasize and explore.

- The center has been outpacing anticipated patient volume since opening, exemplifying the impact of good design on a facility’s effectiveness and its value as a community asset.

- Opportunities that encourage mobility. Corridors that are safe and wide along with walking trails that are easily accessible encourage patients to be ambulatory and promote healing, as long as care is taken to prevent slips and falls by making the pathway as clear and safe as possible.

- At St. Louis Children’s Specialty Care Center, a racetrack corridor inspires patients to ride bikes or tricycles to build strength and coordination and improve mobility. An engaging wall graphic does dual duty as a protective material. Designers embedded milestones and benchmarks in the flooring pattern so patients can visually see progress from day-to-day.

- Following extensive, broad-based planning with a patient and family advisory group, a neuroscience building at Stanford was designed to be completely handicapped accessible, from bathroom stalls to handrails throughout. Corridors are 6 feet wide rather than the standard 5 feet, providing an ample turning radius for mechanized wheelchairs. Though such accommodations are rarely done and exceeded the building code and ADA requirements, for neuroscience patients with mobility, gait or balance problems, it is immensely empowering. “Patients perceive they can go anywhere,” explained Dr. George Tingwald, Director of Medical Planning, Design and Construction at Stanford Health Care.

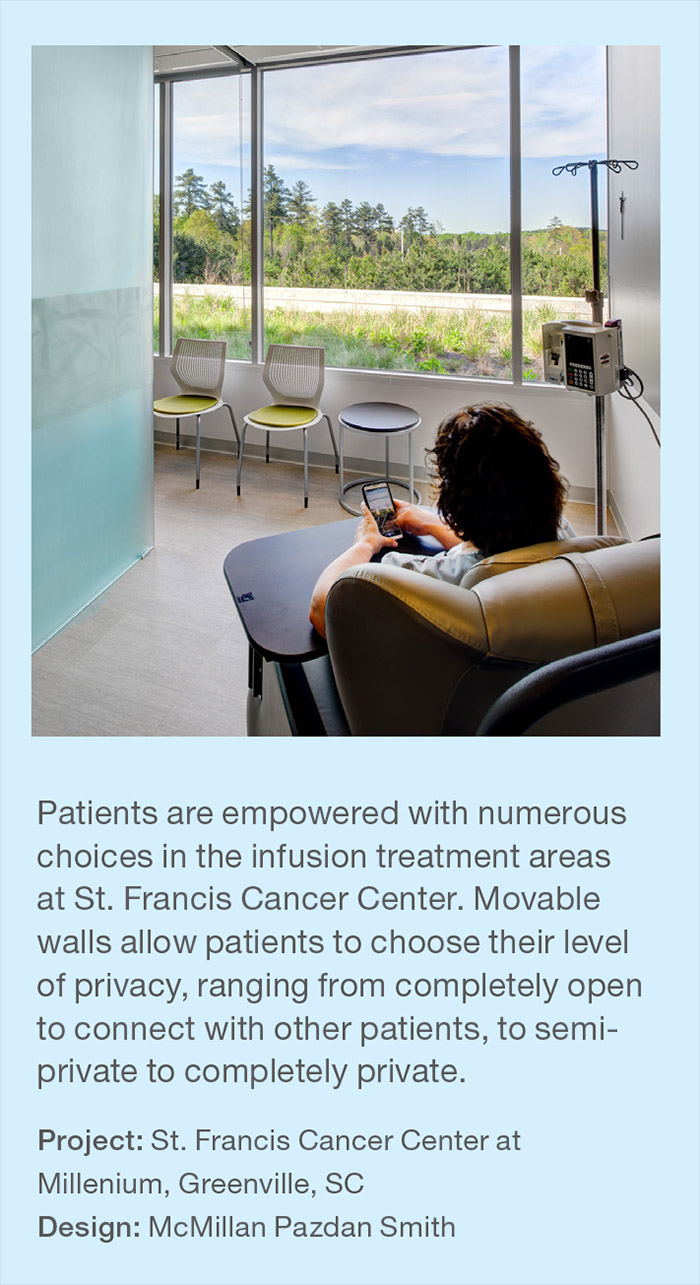

- Empower the patient. Providing some elements of control—which can be as small as bedside adjustments for lighting, window coverings, temperature, television and/or visibility—can improve the patient experience. Providing patient controls also has the ancillary benefit of reducing call button requests for nurses.

- “The physical environment that doesn’t enable patients to do things on their own becomes a bad memory, which can ultimately affect the satisfaction rating for a hospital,“ explained Dr. Pati. “A series of minor negative experiences—even small things such as the patient in a wheelchair who can’t see the reception desk— collectively can become a big negative,” he noted.

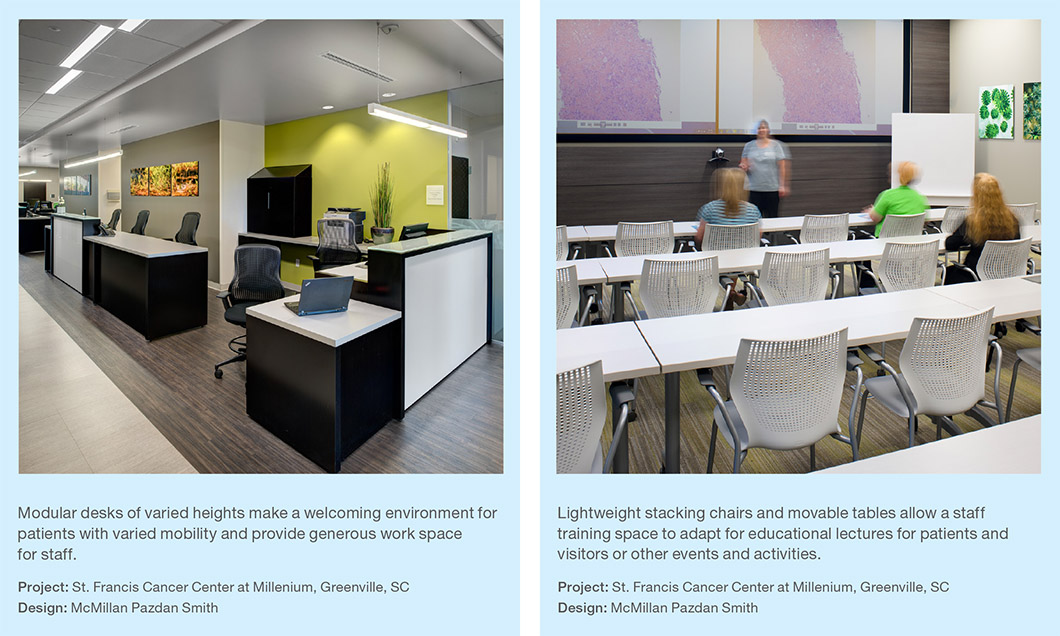

- Providing choice in treatment options is another way facilities empower patients. “We can’t give everybody control, but we can give them choices,” acknowledged Tracey McGee of McMillan Pazdan Smith Architects. At St. Francis Cancer Center at Millenium in South Carolina, her firm provided 52 treatment bays with movable walls in the Oncology Center that range in openness from public to semi-private to completely private, allowing patients to choose their care setting.

- Management reports a 25% increase in referral volume from both patients and doctors since opening the center.

- Such choices support community building that happens to patients undergoing repeat treatment. At Stanford, patient advisory groups have formed social networks that have evolved into support groups. “We have groups of patients who schedule their appointments together rather than spend four hours in infusion or dialysis by themselves,” explained Dr. Tingwald. “There’s a lot more socialization happening and we need to create the environment to have that happen.”

2. Provide Spaces and Comforts for Family and Staff.

A large component of patient-centered care relies on family support, including in-person stays with patients. “The concept of having square footage dedicated to family is hardwired now,” said Todd Cohen, Director of AtSite. “It’s the norm. And when the average length of an ICU inpatient stay is 5 days or more, family members need alternatives and respites from patient rooms.”

Creating a sense of change of venue for visitors and patients might be achieved with variations in furniture styles, types and colors between patient rooms and waiting spaces, according to Jennifer Eno, Senior Interior Designer at NYU Langone.

With stays in rehabilitation centers averaging even longer—around 20 days—facilities are dedicating significant amounts of public space to assure the comfort of family and friends who accompany patients.

Planning Strategies

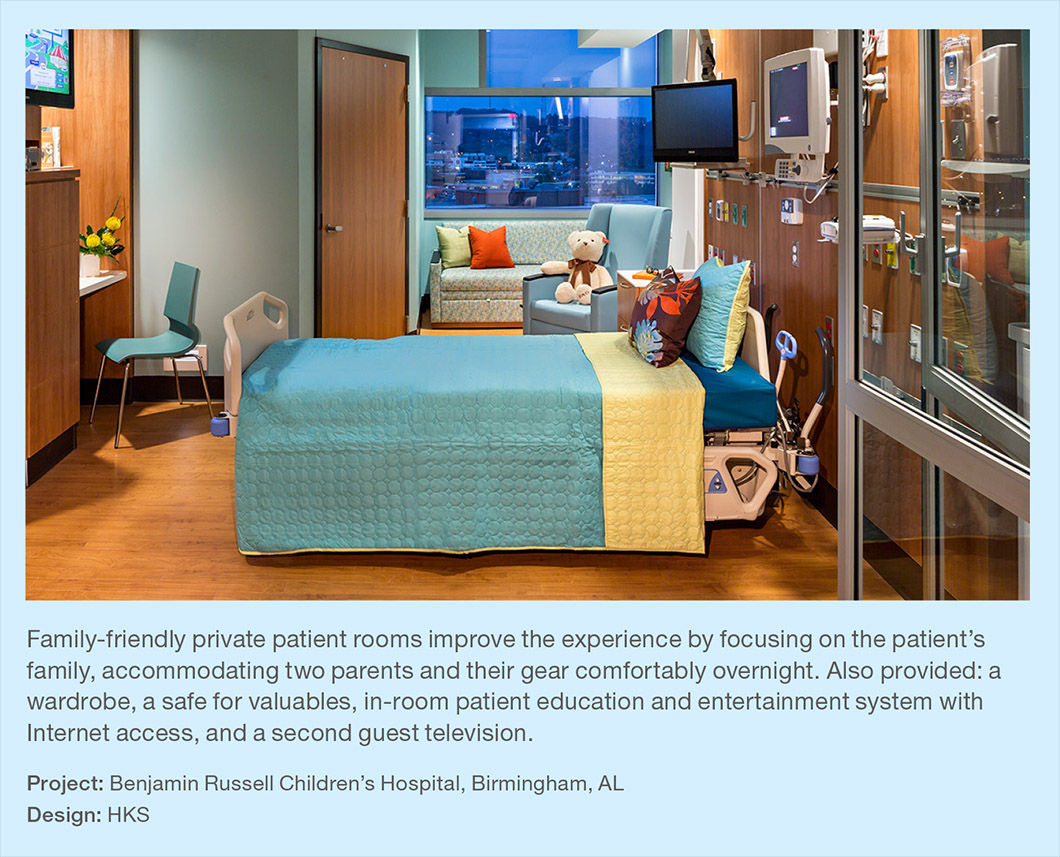

- Allocate in-room space for seating and gear storage. Acknowledging that people don’t come by themselves for a hospital stay, planners typically include two chairs in the patient room, and sometimes a third wall-hung folding chair. Well-planned spaces also accommodate the gear that a friend or relative will likely have on them. “We’re providing an opportunity for people to spend the night in the room and with that, luggage, laptop, cellphone, need for refrigeration and a whole host of important elements,” said Harris Levitt of design firm ZGF.

- Provide a variety of spaces. Delivering many options to support visitors will improve the healthcare experience for both patient and accompanying family. Many institutions are striving to reduce or eliminate waiting areas entirely. When that is not possible, waiting areas should adjust to the rhythms of the space and allow patients and a broad range of visitors a space to relax, chat and/or work throughout the day.

- Options for furnishings might include high top tables near a coffee bar; lounge seating in the TV area, and soft seating that is easily reconfigured when large groups visit and share meals. Tables with chairs support office work, homework, board games and snacking in comfort. Some specific spaces that can meet different needs include:

- Eating spaces. Restaurant style banquettes in the waiting area allow families and visitors to sit down together and eat comfortably while waiting.

- Impromptu gathering spaces. Carving out pleasant spaces for families to gather can be done in creative ways. “We try to utilize building architecture as much as we possibly can,” explained Andrea Sponsel of HKS Architects. “Windows at the end of corridor become natural gathering spaces; they’re a little more secluded, and have that connection to the outdoors. Providing a seating niche or a small lounge furniture grouping lets someone know it’s okay to be there.”

- Private spaces. Multi-purpose consultation rooms provide a quiet space for families to meet with physicians and discuss treatment options, ask and answer questions, process emotions at a turbulent time or take a phone call. Typically equipped with a very small desk with computer, comfortable lounge seating and an end table with a box of tissues, spaces are akin to a psychotherapist’s office, notes Eno, with an occasional addition of a small round table and arm chairs.

- The space should be easily accessible, but feel private and safe, according to Sponsel. “Natural light and views to the outdoors can provide positive distractions and lower stress levels,” she added.

- Workspaces. Quiet reading areas, tables and chairs and phone areas with Wi-Fi and convenient power access allow visitors to work, study or stay in touch with their outside world and responsibilities.

- Provide respite. Artwork, nature areas and/ or unexpected regional retail options allow visitors to take a break or provide positive distraction when stress levels are high. Including a café or juice bar where patients can buy fruits and vegetables reinforces wellness messages about lifestyle changes that will result in better health.

3. Look to Other Industries for Inspiration.

With heightened emphasis on patient satisfaction, and a savvier healthcare customer, designers look to industry models outside healthcare for inspiration and strategies adaptable to healing environments. The airline, retail and hospitality industries provide relevant lessons in creating inviting environments that deliver a superior customer experience.

Planning Strategies

- Hotel and restaurants deliver welcoming environments. While the cleaning and infection-control requirements of a healthcare facility limit material choices, hotels and restaurants do provide examples in delivering a welcoming environment with a warm and modern aesthetic via other means, such as lighting, sound attenuation and furniture arrangement. Hotels know that the customer typically holds the first and last experiences at a destination in their mind, so those are the times when a positive interaction counts the most.

- Informal lounges. Newer healthcare environments are re-thinking lobby spaces, shifting to gathering areas with informal furniture arrangements that present a more relaxed environment suitable for a variety of social and introspective activities.

- Nicer check-in areas. Thoughtfully designed spaces provide a much more pleasant introduction to a potentially anxiety-producing experience. A greeter can answer questions and give directions, but most importantly, provide a personal connection to put stressed people at ease.

- The newly completed University of Minnesota Health Clinics and Surgery Center is based on the concierge model; reception areas and check-in desks do not exist. “Everyone who comes in is greeted by an individual with a tablet who can check in the patient and tell them where they need to go in the building,” explained Jocelyn Stroupe of Cannon Design.

- “Patients are given RFID badges while they’re inside the building so that the staff knows where they are and can monitor the amount of time that they spend waiting. The goal is to keep people feeling a lot more positive about their visits and help to make it smoother, with less down time,” she added.

- Airline clubs provide comfort and choices in waiting. Airlines, another industry in which waiting is unavoidable, provide lessons in making the experience more pleasant.

- “Airline clubs have done a nice job of addressing the situation that a person might be there for a rather long period of time and they need to go about their daily life,” Stroupe explained.

- “They have separate seating areas and options so that people can select where they want to be: whether it’s to sit and eat or watch TV, by a window or not, with other people or not, at counter height seating or low lounge-style seating,” she noted.

- Airlines also provide charging stations to serve waiting customers who need to power their devices. Johns Hopkins has found that airport-style durable multi-portal pole-style charging stations are a better long-term strategy than custom-building technology into furniture, according to Andrea Hyde, former Designer at Johns Hopkins Health Systems and now Director, Design and Architecture at Lifebridge.

- In contrast, NYU Langone has opted for what it considers more of a hospitality model for its family waiting areas. “We use an end table with power; and we do two USB and two data ports,” described designer Jennifer Eno.

- Retail destinations offer strong branding, convenience, easy access and a pleasant customer experience. Applying the customer-focused approach of a retail environment can improve the patient experience.

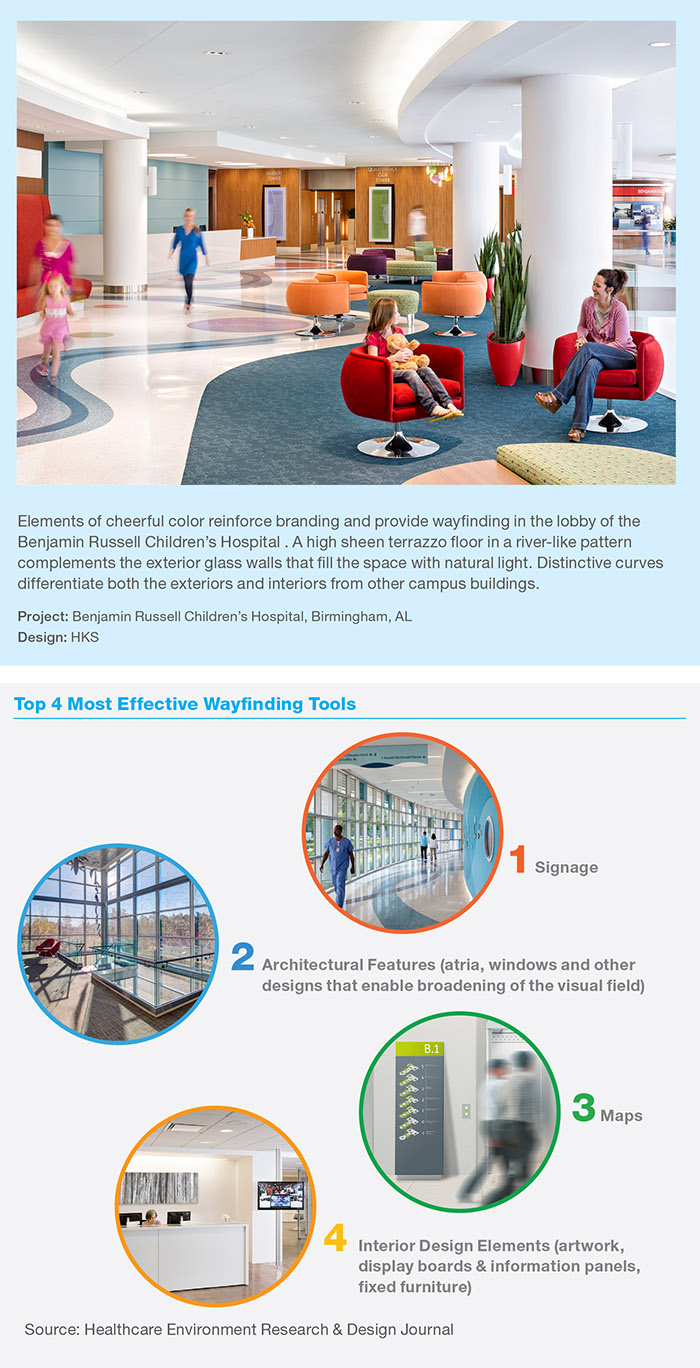

- Intuitive wayfinding. In the emergency department and in high stress situations, people don’t read, so they need to be directed in the simplest, most intuitive way, explained designer Andrea Sponsel of HKS.

- Landmarks. Leveraging architecture and other landmarks can ease maneuvering throughout a large institution. Signage and maps will always play a significant role in wayfinding, but large atrium spaces were found to be among the most effective directional devices, according to Dr. Pati of Texas Tech. “Our visual connectivity is restricted by walls and floors and ceilings. Atrium spaces enlarge the visual field beyond the walls and give a lot more additional clues,” he explained. Likewise maintaining sightlines down corridors, particularly off elevators, which also expands the visual field, according to Dr. Pati, who added that furniture and artwork can also be wayfinding attributes.

- Curb appeal. Overall design counts in retail-style settings. As the healthcare market becomes ever more consumerdriven, health providers must find new ways to compete in a crowded marketplace, according to Sarah Bader of Gensler.

- Retail establishments have mastered leveraging design to drive sales. Expansive glass storefronts welcome passersby while ushering in daylight, creating a more inviting environment for shoppers, employees and neighbors.

- At Whitman-Walker Health in Washington DC, the success of its pharmacy was vital to sustaining its center. Designers relocated a crowded, not-retail friendly pharmacy formerly hidden in a clinic waiting area to a space adjacent to the front door of the clinic. Now visible from an active urban street and branded with bright colors, it has a significant retail presence that has increased foot traffic, sales and clinic visits.

- Location. Foot traffic generated by adjacency is an important attraction, just as in retail malls, according to the real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield. Adjacency can represent convenience for patients who can accomplish many more tasks during doctor visits, as opposed to single purpose medical spaces.

- One-stop shopping. Taking cues from the retail industry, hospitals are increasingly embracing a one-stop shop approach that has become a defining trend in outpatient facilities. Facilities are offering cafés, safety shops for car seats and other childrelated equipment, classroom spaces for community programs and pharmacies. By clustering related amenities under one roof, centers add value beyond providing excellent care and further respond to the needs of the community.

- Restaurant style waiting. When waiting cannot be avoided, Dr. Pati suggests taking a lesson from restaurants in retail centers and giving guests a pager so they can do something else nearby. It can turn a potentially negative experience into a pleasant one.

4. Lean Approaches to Alternative Care Models and Modern Workplaces.

In the healthcare environment, where managers are asked to do more with less (staff, technology, time and workspace), the tenets of lean thinking—reducing waste, improving productivity and efficiency and achieving the best clinical outcomes—are increasingly prevalent in spaces that support new modes of care delivery. Among frequently employed lean strategies are reducing the number of people necessary for a process, automating as much as possible and eliminating waiting times.

However, leaner does not necessarily mean smaller. “You get better throughput if you have a little more space,” expressed Dr. Tingwald, “as well as significant operational savings.”

At St. Louis Children’s Hospital Specialty Care Center, designers organized the overall floorplate to streamline travel distances and separate traffic flows while providing flexibility between different suites as volumes change over time. Space is organized so circulation paths yield continuous views of the landscape from public corridors and waiting rooms while also providing daylight and wayfinding cues.

Planning Strategies

- On Stage/Off Stage Model. Inspired by the Disney model that conceals staff movements backstage to ensure a superior guest experience, the healthcare variation separates public areas and patient spaces from private, behind-thescenes work and staff areas.

- In the lean model, separate and dedicated patient and provider zones and paths of travel enhance the patient experience and improve efficiency. Rather than be redirected through multiple offices and facilities, patients remain in a single room with dual access. Clinicians rotate to see them, facilitating all of a patient’s needs within one space and a single visit in streamlined fashion.

- “All the services come to the patient,” explained Harris Levitt of ZGF, “and nothing feels medical until you get into the exam room.” In addition to lessening the need for separate waiting areas, it creates greater efficiencies and lower stress. With spaces freed up from the elimination (or minimizing) of common waiting areas, the onstage/ offstage model can accommodate family members comfortably, which is especially appreciated when young children need to come along or the elderly are being cared for.

- Fewer waiting spaces allow more exam rooms, getting clinicians in much quicker and often allowing physicians to see one additional patient a day than spaces with private doctor offices.

- The model also guards against infection. For example, a well-baby visit no longer has to be separated from a contagious child. Separating patients can lower patient anxiety, allowing them to focus on healing.

- ZGF Architects used lean methodologies at the award-winning Everett Clinic at Smokey Point Medical Center in Washington. Management sought to achieve low-to-no volume wait by cutting patient waiting by more than 25%, and getting patients into a room with a medical assistant about two minutes after arrival at the clinic. Exam rooms contain scales and blood draw equipment, eliminating patient travel to labs, explained Levitt. In lieu of a large, traditional waiting area, patient “pause” areas furnished with cushioned benches are located directly outside exam rooms.

- Reducing non-patient care space 23% at Everett yielded savings of $2.1 million. It also provided 33% increase in efficiency of overall square footage.

- Workspaces that support teamwork, collaboration and privacy. Changing modes of care delivery have had huge impact on healthcare work environments, changing the nature of how many spaces are used. “So much happens at the bedside now with regards to charting and keeping records,” said NYU Langone’s Eno, noting the importance of supplying furniture and layouts that allow providers to make eye contact when taking patient information.

- “With the advent of that, the old nurse’s station has become much more of an information hub. There’s usually a unit clerk who can help direct family members or physicians or anyone visiting. We provide private charting stations like a phone booth, where a staff member can get in, make a phone call, so there’s a little bit of privacy, and you’re off the beaten path,” she said.

- As healthcare becomes more of a team sport, group workspaces are replacing private offices.

- “With an increasing demand for teambased coordinated care models, we are using very different designs for staff work areas in ambulatory settings than we have in the past,” remarked Tracey McGee of McMillan Pazdan Smith. “Traditionally the clinic nurse station was similar to the hospital nurse station, located on the corridor with both work and transaction height surfaces. Physicians had private offices. Now we see a shift to open team work rooms with less demand for private offices. Team work areas better support situational awareness among team members, work sharing and communication.”

- Dual-duty enclosed consultation rooms accommodate occasional private meetings to review case details with other staff, patients and family. Keeping to a modular format allows for them to flex and switch to exam rooms when needed. “These spaces often function as multi-purpose rooms that are shared among physicians and staff. They might also be used by visiting providers who don’t have dedicated exam rooms, such as nutritionists,” McGee explained.

- Multi-disciplinary team space also encourages cross-pollination of departments. In clinics such as The Everett Clinic in Washington and the University of Minnesota Health Clinics and Surgery Center, which contain no dedicated physician offices or assigned offices, touchdown spaces are provided in a variety of formats including private and open space for work or collaboration across disciplines.

- Likewise at NYU Langone. “Because we’re a teaching hospital, we have huddle spaces where you can pull your team together: med students, attendings, doctors. Everyone can gather round a small table and a wall-mounted monitor screen, and be brought up to date on the cases before proceeding to rounds and clinical evaluations,” Eno related.

- Informal interaction across departments can also be encouraged with design. At the University of Minnesota facility, a threestory staff lounge interconnects three floors of clinics and provides opportunities for people to talk with staff who work in other parts of the building.

- The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center encourages spontaneous collisions and interaction via its layout. One of its facilities is a collaborative research building, with two wings of offices and two wings of research, described Lucy Nye, Manager, Adminstration/Interiors/ Activations Resources. “You have to walk through the center to get to your office.”

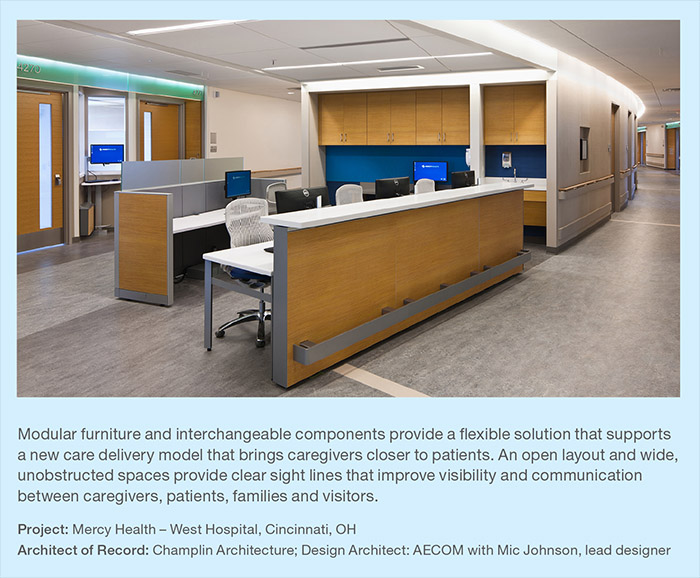

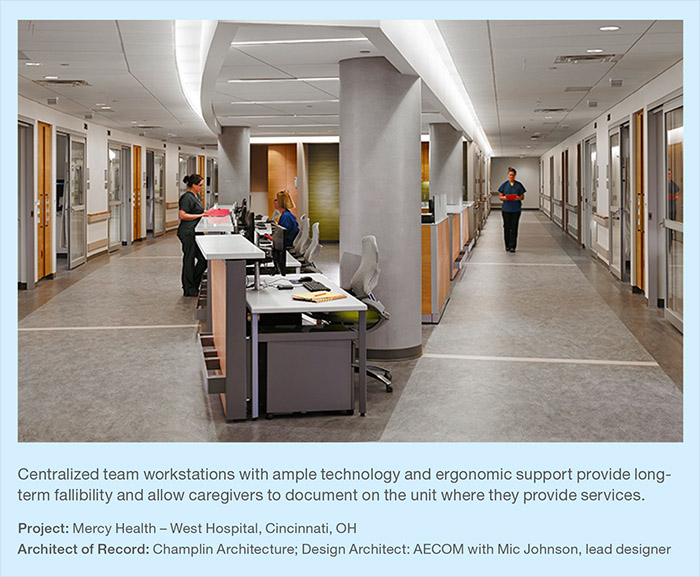

- Staff spaces that support connections, relaxation and respites. Research shows that providing pleasant staff environments, with generous, well thought-out spaces for people and material flow, is reflected in better patient outcomes. Case studies such as one done by Knoll and Mercy Health on its West Hospital indicate that staff satisfaction may be linked to improvements in patient satisfaction ratings.

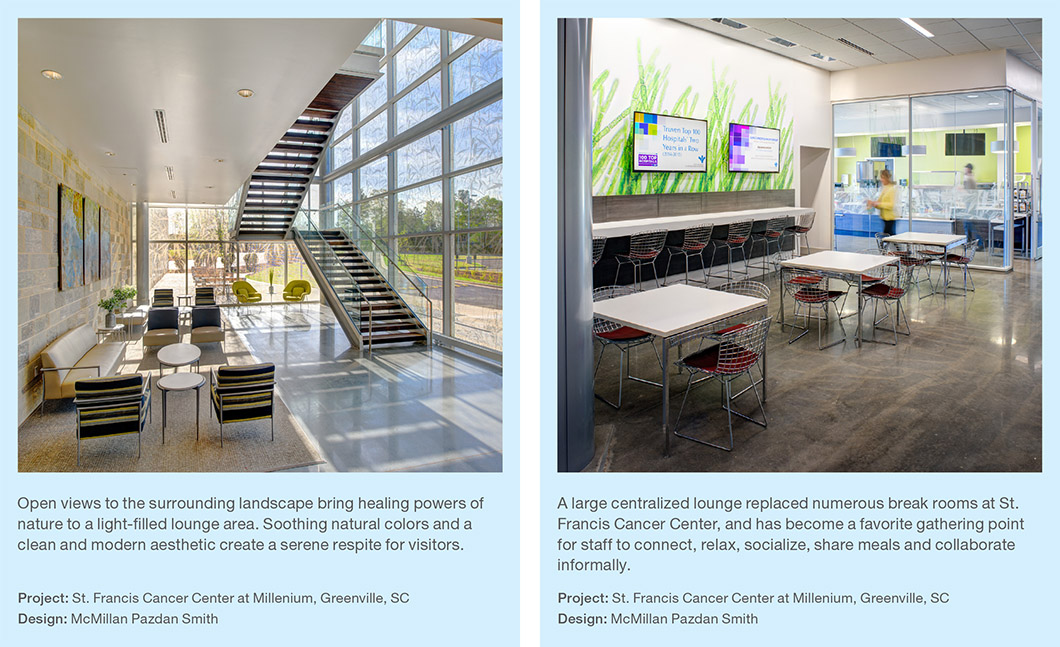

- Much like private offices are being replaced with open collaboration spaces, multiple breakrooms are increasingly being centralized into a large staff lounge.

- At the St. Francis Cancer Center, McMillan Pazdan Smith designed a 1,200-squarefoot open space lounge serving multiple departments complete with wall-mounted TVs, lockers and a generous island where vendors frequently set up food for the day.

- “We found that if you group people all together, it’s more relaxing to them,” said Tracey McGee. It’s a social opportunity which people enjoy. It gives people a chance to come together during the day and see people they don’t necessarily see or work with,” she continued.

- “They actually have conversations about patients and things. It creates another space for collaboration,” McGee noted.

- In addition to social spaces, staff appreciate private respite areas to take a break during what is often a stressful, emotionally charged day. In inpatient units, small staff private rooms might have subdued lighting, two or three lounge chairs, perhaps a recliner, and a water feature for tranquility.

- While codes require each patient room have a window, no such regulation applies to staff spaces, even though daylight is associated with a better, more productive work experience. For many years, staff lounges were in the middle of the building with no access to natural light. Today designers strive to bring in natural light and outdoor views, putting skylights in windowless rooms when possible.

5. Design for Flexibility.

It has been said that the only true hospital of the future is the one that maximizes the ability to accommodate change. Building in flexibility in spaces and furnishings wherever possible is the best insurance of creating an environment that can adapt smoothly as medicine and technology further advance.

Planning Strategies

- Modular spaces with multiple functions. Technology and work flow changes demand modular spaces for flexibility and efficiency. Using a single modular plan allows exam rooms to flex to procedure rooms or other uses on a day-to-day or long-term basis. When rooms flex enough to bring equipment in and out, patients can stay comfortably in place rather than be relocated.

- When all components are in the same place in each room, the increased efficiency allows for patients to have more family in the room, streamlines adaptability between departments, and simplifies longterm maintenance and replacement.

- A lean planning approach at The Everett Clinic led to a modular solution, yielding a 30% reduction in exam rooms (from 82 to 62 right-sized rooms) and 92% increase in flexibility.

- At American Family Children’s Hospital in Wisconsin, a universal design concept was adopted, standardizing on a single size for exam rooms, treatment rooms and inpatient rooms throughout the facility, enabling one area to absorb overflow traffic from the other without making extensive accommodations.

- The strategy comes into play frequently at night when numbers of emergency department patients increase. Adjacent exam rooms that are part of the clinic during the day can easily handle nighttime overflow and support treatment, explained Ardis Hutchins, UW Health Interior Architect.

- Varied options for patient education, community events. To support efforts to maintain patient health, facilities are building in means to deliver education to patients and families and encourage wellness among employees, patients and the community.

- Some organizations lead by example, supporting wellness with onsite facilities and amenities such as gyms, exercise areas, pools, yoga classes and demonstration kitchens that encourage patients and employees to build healthy habits into their lives.

- Group education sessions and workshops are presented in larger multi-purpose rooms covering topics such as nutrition, diabetes, smoking cessation and prenatal and infant care. Spaces need to flex to accommodate different size groups and types of events and seating configurations. Multi-function furniture, such as mobile tables with flip down tops and stacking chairs add options and save space. “The more a component can do the better, said McGee, “especially if it’s movable and reconfigurable.”

- In many cases, spaces are open to the community at designated hours. Many institutions also consider such investments a marketing element to reach out to the community.

- At the Whittier Street Health Center in Boston, a unique model that serves diverse communities, designers used movable walls so the space could function as a men’s health clinic during the day. It opens up to a larger space with tables and chairs for Saturday seminars and breakout sessions. In between it hosts computer classes for teens.

- Flexible furniture that adapts. New collaborative workstyles need to be supported with furniture that flexes to accommodate changing team sizes and activities throughout the 24-hour healthcare workday. Movable, modular components can also be a tool in change management, allowing for gradual adaptation and/or easy reconfiguration of shared offices or other new concepts.

- “Sometimes they’re trying a new model of work, and they’re not sure how it’s going to work. It’s easier to change the flexible furniture than it is to build walls,” said Cindy Flinchum, UW Health Facilities Designer. Most of the staff areas—”beehives” is the term used internally at UW Health—use system furniture for exactly that type of flexibility and to support the new team spaces that are replacing private offices in most of their environments.

- Modularity for future flexibility. Mercy Health’s West Hospital found modular furniture and its interchangeable components were the ideal solution for its needs. “First, it easily accommodates changes in workflow, equipment or departmental growth with minimal disruption to staff and patients. Second, it has a slightly smaller footprint, which fit the scaled-down workspaces. Third, it neatly houses wiring and cables,” explained designer Kristie Pudlock, Champlin Architects.

- Modular systems also afforded versatility within the actual workstations. “It allows for various heights of partitions and glass panels to help with audible privacy. It easily accommodates both individual and shared workstations for two or four people. It works freestanding or connected within open or closed workstations and private offices,” related facility planner Larry Bagby.

- Systems furniture provides highly responsive flexibility within UW Health’s staff work areas. “For example, the emergency department decided they did not want any barriers between the workspaces, feeling they wanted to see each other and talk to each other,” recalled architect Ardis Hutchins. “Accommodating the ED was as simple as taking down the panels and half-high partitions.”

- Adaptable furniture that ergonomically supports multiple users in shared spaces. Adjustable furniture accommodates the round-the-clock activity by users of varied sizes that is inherent in the healthcare workplace.

- Furniture also needs to accommodate the growing influence of high technology, monitor-intensive work now required in dynamic healthcare environments. Providing flexibility and proper ergonomics in a shared work area should include a sit-to-stand desk and ergonomic fully adjustable seating for all functions and disciplines, related Andrea Hyde, Director, Design and Architecture, LifeBridge.

- “24/7 multi-user work areas cannot be served well with fixed-height laminate surfaces with keyboard trays,” she emphasized.

- The growth in monitor sizes and popularity of dual monitor workstations is demanding deeper surfaces to minimize eye strain, added UW Health’s Hutchins, who finds 30-inch deep surfaces more accommodating than 24-inch options.

- At Mercy Health’s West Hospital, monitor arms can be used sitting or standing on either side of the station, raised, lowered and swiveled easily to accommodate different people. A post-occupancy survey revealed that 96% of users felt ergonomic elements including monitor arms and position of keyboard and mouse added to their comfort while working on the computer.

- Technology-equipped meeting spaces. Conference spaces are often shared among floors or departments, necessitating building in as much flexibility as possible to accommodate a range of uses. Sometimes offsite specialists or team members need to be consulted about a particular diagnosis, so furniture solutions should accommodate technology-based communication such as Telemed, WebEx and Skype.

Summary

Change may be slow in healthcare, but the reality of economics and industry reform measures, combined with a growing, consumer-savvy patient base, are forcing healthcare providers and the architecture and design community to adapt quickly and develop new, innovative solutions.

As the healthcare industry continues to change and reinvent itself, institutions are challenged to respond with models that meet three primary goals: improving the patient experience, improving the health of the population and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare and deriving greater ROI on investment.

New models respond to the changing agenda, as well as the shifting healthcare workplace, which is much more collaborative than it was in the past.

Industry changes are urging re-thinking of physical spaces to support team-based care delivery, the ever-advancing medical technologies they utilize on a daily basis and the communication technologies that connect them to consultants in other locations.

A more market-driven model is emerging, empowering consumers with choice and inspiring institutions to deliver a positive healthcare experience. Fresh thinking has resulted in environments that make both the patient and family experience much more pleasant. Taking cues from industries such as retail, hospitality and the airlines, designers and planners are creating spaces that are a far cry from clinical institutions of the past, and more closely resemble lounges, fine restaurants and branded hotel experiences.

With the advent of patient choice, convenience, comfort and education, institutions can achieve a higher satisfaction rating, better patient experience and positive outcome.

Among the most successful environments are those that start with lean thinking, re-examining each and every step in the process to eliminate waste and allow for future flexibility.

Leveraging the power of design can add value beyond providing excellent care in the healthcare built environment. It can create a welcoming environment that attracts patients and delivers a superior experience to patients, family, visitors and staff. It can also respond to the needs of the community; support recruitment and retention efforts, improve operations and efficiency and ultimately drive financial success.

Future Outlook

More changes are in store on the healthcare front. Despite uncertainty about the next phase of healthcare reform, demographics favor continued growth in the healthcare sector. Industry prognosticators and institutions maintain a bullish outlook as well. The American Institute of Architects forecasts that construction spending will double in 2017, and Healthcare Facilities Management reports that 19% of health systems had an ambulatory project underway in 2016 and 18% are planning a new one in 2017. By providing the ultimate in convenience, technology applications are poised to revolutionize the industry, connecting providers with patients in any location and improving access to healthcare while achieving greater accuracy and efficiency. Dr. George Tingwald predicts virtual care will drastically shrink the number of clinic visits and ultimately space requirements, much like technology has replaced many bank tellers and travel agents.

Ninety-two percent of executives expect that the hospital of the future will not be a hospital at all and that high value post-acute care networks will be a key area of focus over the next three years. However, 94% feel creating such networks will be their greatest challenge in that same time period, according to Premier’s Economic Outlook Survey.

Some states such as California already have highly market-driven programs in place that recognize the strength of the patient consumer and will likely serve as models for other states to adapt.

The future of healthcare relies on successfully integrating the new outcome-based model and its accompanying mindset based on patient self-management and accountability. Success also hinges on patient management of lifestyle and chronic conditions, the most common and costly of all health problems, but also the most preventable.

Early reports show the new outcome-based model is succeeding at an economic level. Research recently found that U.S. hospitals that deliver “superior” customer experience achieve net margins that are 50% higher, on average, than those of hospitals providing “average” customer experience. The study by Accenture compared six years of hospital margin data with HCAHPS scores and found that hospital margins and revenues among the top HCAHPS performers are growing at an above-average rate and revenue growth is outpacing expenses in these hospitals.

As attitudes and policies change, and delivery models continue to shift, the built environment will play a significant role in American healthcare and the corresponding patient experience, one likely to affect virtually every individual at one point in their life.

Click Here to Download "Modern Medicine"

Special Thanks

A special thanks to the following individuals:

Lilliana Alvarado, CHID, EDAC, IIDA, NCIDQ,

LEED AP

Design Principal

Uphealing

New York, NY / Bedford, NH

Sarah Bader

Managing Director, Principal, Health &

Wellness Practice Leader

Gensler

Chicago

Larry Bagby

Assistant VP

Florida Hospital

Tampa, FL

John Baltosiewich

Director, Supply Chain Sustainability

Holy Cross Health

Montgomery County, MD

Becky Baron

National Director, Strategic Real Estate

Planning & Transition

Catholic Health Initiatives

Denver, CO

Carol Beasley

Senior Vice President

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Cambridge, MA

Lisa Bonnet, NCIDQ, LEED AP

Interior Designer

Morris Switzer Environments for Health, LLC

Boston, MA

Rebecca Brown, IIDA

Director of Business Development

Creative Business Interiors

Madison, WI

Todd M. Cohen, FACHE, EDAC

Director

AtSite

Washington, DC

Kim Dalton

Principal

Dalton Interiors

Scottsdale, AZ

Tama Duffy Day

Firm-wide Leader of Health &

Wellness Practice

Gensler

Chicago

Geraldine Drake, NCIDQ, LEED Green

Associate

Interior Design Director

Quinn Evans Architects

Ann Arbor, MI

Jennifer Eno

Senior Interior Designer

NYU Langone Medical Center

New York, NY

Cindy Flinchum

Facilities Planner

UW Health

Madison, WI

Ardis Hutchins, AIA, IIDA, CHID, EDAC

Interior Architect

UW Health

Madison, WI

Andrea V. Hyde, CHID, MDCID

Director - Design and Architecture

LifeBridge Health Real Estate, Planning &

Construction Department

Baltimore, MD

Harris Levitt

Associate Partner

ZGF Architects LLP

Seattle, WA

Tracey McGee

Associate, Healthcare Planner & Project

Manager

McMillan Pazdan Smith

Greenville, SC

Lucy Nye

Interiors/Activation Resources

University of Texas MD Anderson

Cancer Center

Houston, TX

Debajyoti Pati, PhD, FIIA, IDEC, LEED AP

Professor and Rockwell Endowment Chair,

Department of Design

Texas Tech University

Lubbock, TX

Kristie Pudlock

Interior Designer

Champlin Architecture

Toledo, OH

Anita Rossen

Principal

ZGF Architects LLP

Seattle, WA

Andrea Sponsel

Vice President

HKS, Inc.

Dallas, TX

Jocelyn Stroupe, CHID, EDAC, IIDA, ASID

Principal

Cannon Design

Chicago, IL

Dr. George Tingwald

Director of Medical Planning,

Design & Construction

Stanford Health Care

Menlo Park, CA

References & Additional Reading

Accenture. 2016. “U.S. Hospitals that Provide Superior Patient Experience Generate 50 Percent Higher Financial Performance than Average Providers, Accenture Finds,” May 11, https://newsroom.accenture.com/news/us-hospitals-that-provide-superiorpatient-experience-generate-50-percenthigher-financial-performance-than-averageproviders-accenture-finds.htm

Barista, David. 2013. “Five radical trends in outpatient facility design,” Building Design & Construction, February 14, http://www.bdcnetwork.com/5-radical-trends-outpatientfacility-design

BaRoss, Carolyn. 2015. “Designing for Health: Responding to Shifting Patient Demographics Through Empathetic Design,” Contract Magazine, September 15, http://www.contractdesign.com/practice/healthcare/Designing-for-Health-Responding-to-Shifting-Patient-Demographics-Through-Empathic-Design-36790.shtml/

Barker, John and Ed Pocock, AIA and Charles Huber. 2015. “The Future of Ambulatory Care,” Practicing Architecture Knowledge Communities, American Institute of Architects, http://www.aia.org/practicing/groups/kc/AIAB086508

Cushman & Wakefield. 2013. “Heading to the Mall for Healthcare?”. Cushman & Wakefield Healthcare Practices Group & Retail Services Publication, April, http://www.cushmanwakefield.us/en/researchand-insight/2013/heading-to-the-mall-forhealthcare-apr-13/

DiNardo, Anne. 2016. “Showcase 2016: Today’s Healthcare Designs Are Making a Statement,” Healthcare Design, July 8, http://www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/showcase-2016-todays-healthcare-designsare-making-statement

DiNardo, Anne. 2016. “Forward Thinkers: Focus on Academic Medical Centers. 2016 Healthcare Design,” August 16, http://www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/showcase-2016-todays-healthcare-designsare-making-statement

DuBose, Jennifer and Ross Westlake. 2015. “Research Weighs Effects of Healthcare Workspaces on Team-based Care,” Healthcare Design, April 22, http://www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/research-weighs-effects-healthcareworkspaces-team-based-care

Duffy Day, Tama. 2014. “Straighten Up and Fly Right: What Hospitals Can Learn from Airports,” GensleronCities, April 30, http://www.gensleron.com/cities/2014/4/30/straighten-up-and-fly-right-what-hospitalscan-learn-from-ai.html

Duffy Day, Tama. 2015. “The Power of Design in Retail Health: 5 Flips to Consider,” GensleronCities, July 27, http://www.gensleron.com/cities/2015/7/27/the-power-ofdesign-in-retail-health-5-flips-to-consider.html

Egan, Kate. 2014. “POE Measures Success of New Clinic Operational Models,” Healthcare Design, August 7. http://www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/poemeasures-success-new-clinic-operationalmodels

Eagle, Amy. 2014. “Ambulatory facility designs | How the new generation is taking shape, Health Facilities Management, April 2, http://www.hfmmagazine.com/articles/1254?dcrPath=%2Ftemplatedata%2FHF_Common%2FNewsArticle%2Fdata%2FHFM%2FMagazine%2F2014%2FApr%2F0414HFM_Coverstory

Eagle, Amy. 2016. “Building Patient Satisfaction | Physical environment improvements can lead to better patient experience and HCAHPS scores, Health Facilities Management, August 3, http://www.hfmmagazine.com/articles/2314-building-patient-satisfaction%26utm_source%3dhfmdesignnews%26utm_medium%3demail%26utm_campaign%3dHFM?eid=254470187&bid=1508058

Hannon, James T. 2010. “The Facility Response to Health Reform,” Practicing Architecture Knowledge Communities, American Institute of Architects, The Academy Journal of the Academy of Architecture for Health (AAH), November 10, http://www.aia.org/practicing/groups/kc/AIAB086505

Health Research & Educational Trust. 2016. “Improving the Patient Experience through the Health Care Physical Environment” Health Research & Educational Trust, March, http://www.hpoe.org/resources/hpoehretahaguides/2823

Kovac Silvis, Jennifer. 2014. “Designing for Wellness: The Healthcare Campus of the Future,” Healthcare Design, April 21, http://www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/designing-wellness-healthcare-campus-future

Kovac Silvis, Jennifer. 2015. “Healthcare Design Industry Reaches a Middle Ground,” Healthcare Design, September 21, http://www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/healthcare-design-reaches-middle-ground

Modern Healthcare. 2016. “Transparency, Collaboration, Disruption: What Executives Shared at Breakthroughs,” http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20160623/SPONSORED/306239998

O’Connell, Kim A. 2014. “Is there a Doctor in the Firm? (Or a Nurse in the Studio?)” AIArchitect, February 21, http://www.aia.org/practicing/AIAB101671

Pati, Debajyoti and Thomas E. Harvey, Jr., Douglas A. Willis, Sipra Pati. 2015. “Identifying Elements of the Health Care Environment That Contribute to Wayfinding,” Health Environments Research & Design Journal

Pati, Debajyoti and Pamela Redden. 2015. “Does The Decentralized Nursing Model Deliver?” Healthcare Design, August 6, http://www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/does-decentralized-nursing-model-deliver

Stouffer, Jeff. 2013. “What’s Trending in Ambulatory Care Design,” Healthcare Daily, May 16, http://healthcare.dmagazine.com/2013/05/16/whats-trending-inambulatory-care-design/

Stroupe, Jocelyn. 2016. “Elevated Experience. Enhanced Convenience,” Medical Construction & Design, May/June, http://mcdmag.epubxp.com/i/677235-mayjun-2016/46?utm_campaign=Health%20General&utm_content

Terry, Cinda Z. and Brenda Bush. 2012. “Reimagining the Medical Office Building,” Healthcare Design, August 27, http://www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/article/reimagining-medical-office-building-

Upali Nanda (PI) and Seluga Sekanwagi, Adeleh Nejati, Lindsay Graham, and Sipra Pati. 2015. “Clinic 20XX: Designing For an Ever-Changing Present. Center for Advanced Design Research and Evaluation,” http://www.cadreresearch.org/projects/clinic-20xx/

Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Architects. 2013. “The Everett Clinic, Smokey Point Medical Center,” https://issuu.com/zgfarchitectsllp/docs/the_everett_clinic?e=5145757/261163