In a city full of New York institutions, the Four Seasons stands out as a true cultural icon and architectural landmark. Since its opening in 1959 in the Seagram Building (itself a standard-setting modern icon), the restaurant is credited with pioneering a number of changes that are now common to the culinary world: presenting English-printed menus, locally-sourced ingredients and seasonal dishes.

But it was the remarkable interior at the Four Seasons that made the restaurant a magnet. Designed by Philip Johnson and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (the building's architect), the stunning space included Knoll furniture; the lean, cantilevered chrome Four Seasons Barstool, believed to be a collaborative effort between Mies and Johnson, was designed specifically for the restaurant in 1958. The combination of high design and a forward-thinking kitchen proved irresistible to the New York City's elite. By the late 1970s, the Four Seasons' two public dining rooms had became known for “power lunch”—a phrase first coined in a 1979 Esquire article by Lee Eisenberg about the long, business-centered noon outings at the restaurant.

The Four Seasons Restaurant endured as an architectural and culinary landmark of profound significance for the last 57 years, until news broke in 2015 that Aby Rosen, owner of the Seagram Building, would not renew the lease of the restaurant, signaling its closure.

Although the restaurant interior was granted landmark status by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee in 1989, the provisionary protection did not apply to the specially-designed silverware, furniture and fixings, the sum of which formed the Mies and Johnson design. This includes over a hundred pieces of serviceware designed by L. Garth and Ada Louise Huxtable, ranging from champagne glasses to bread trays. After news broke of the restaurant’s imminent closure, Wright secured the rights to auction off those pieces not protected by the New York City Landmark status. In light of the news surrounding the restaurant’s upcoming redesign, Knoll Inspiration decided to revisit the restaurant as it was originally designed.

The Pool Room at The Four Seasons, August, 1959. Image courtesy of Bettmann/Corbis.

“The stark modernism of it threw me—I thought it was going to be like the Oak Room. And then, by the second time you go, you appreciate it. And then by the fifth time, you realize it’s the most beautiful restaurant in the world.”

—Graydon Carter

The Four Seasons was designed to complement the architectural achievement of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building. A masterpiece in its own right, upon completion the Seagram Building was instantly proclaimed "the millenium's most important building" by architectural critic Herbert Muschamp.

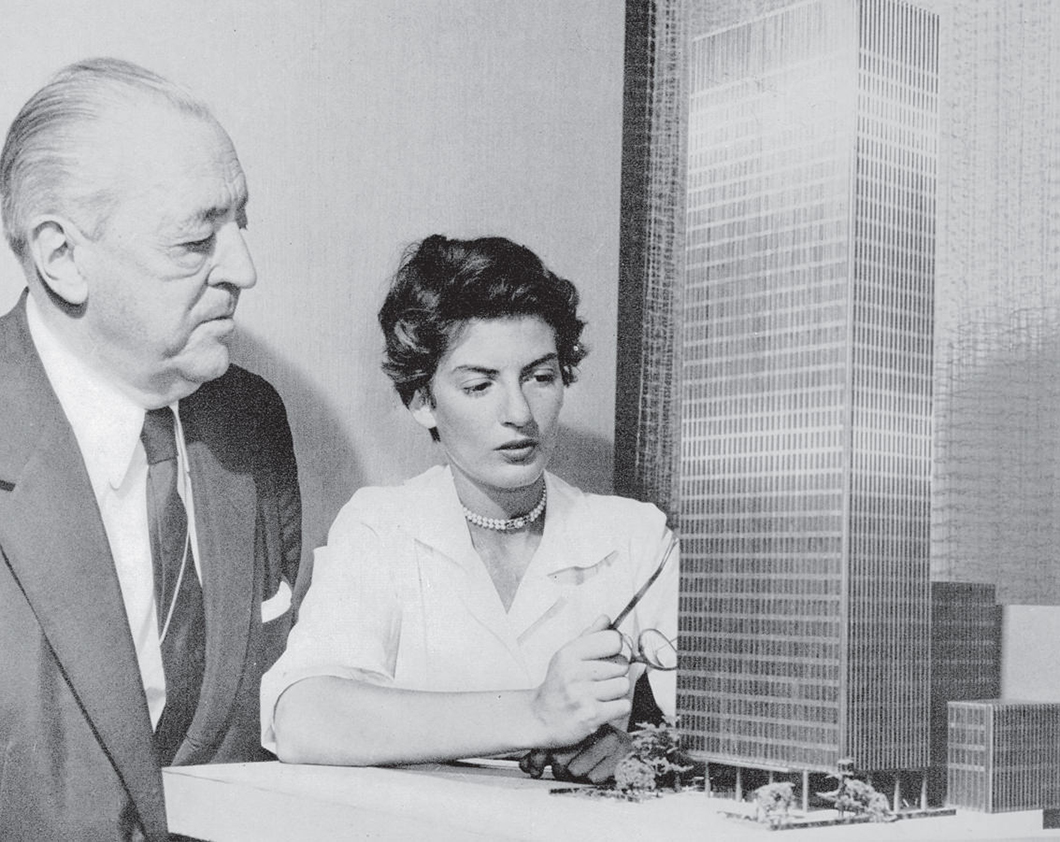

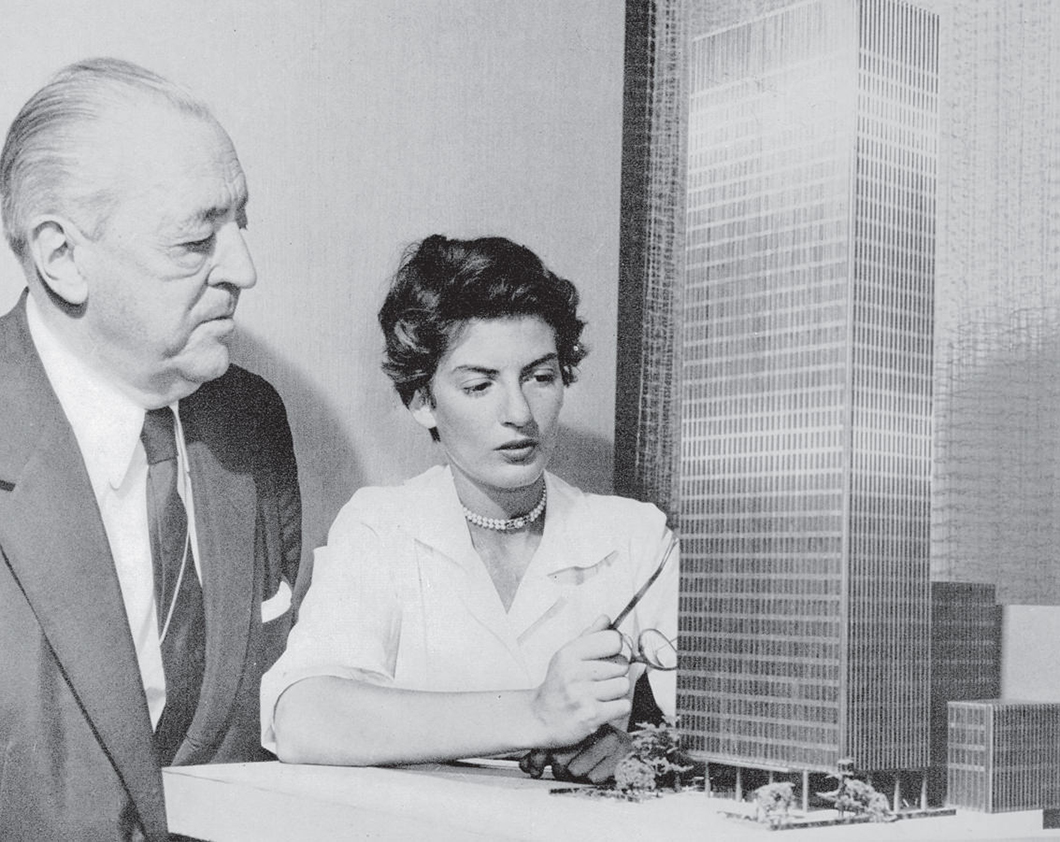

Phyllis Lambert and Mies van der Rohe with a model of the Seagram Building, c. 1958. Image courtesy of Phyllis Lambert, Canadian Center for Architecture.

Both the project and the selection of its architect were willed into being by 26-year-old Phyllis Lambert, daughter of Samuel Bronfman, baron of the distilling empire Seagrams. After reviewing her fathers’ original plans for the site, she wrote a lengthy missive which started with the word “no” printed seven times, expressing her absolute disdain for the proposed design. She wrote, “You must put up a building which expresses the best of the society in which you live, and at the same time your hopes for the betterment of this society.”

“You must put up a building which expresses the best of the society in which you live, and at the same time your hopes for the betterment of this society.”

—Phyllis Lambert

Hans Wegner's PP-501 chairs at The Four Seasons Restaurant. Image courtesy of Wright.

The headstrong aesthete, now referred to as the "Joan of Architecture," was appointed Director of Planning and charged with selecting a worthy architect for the project. With the help of Philip Johnson, who had recently left the Museum of Modern Art to devote himself to his newly-formed architectural practice, Lambert narrowed down her shortlist—which had included Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius, Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph and I. M. Pei—until only Mies and Le Corbusier remained. Lambert chose Mies, who in turn asked Johnson to execute the building's interiors and, of course, the restaurant that was planned for its ground floor.

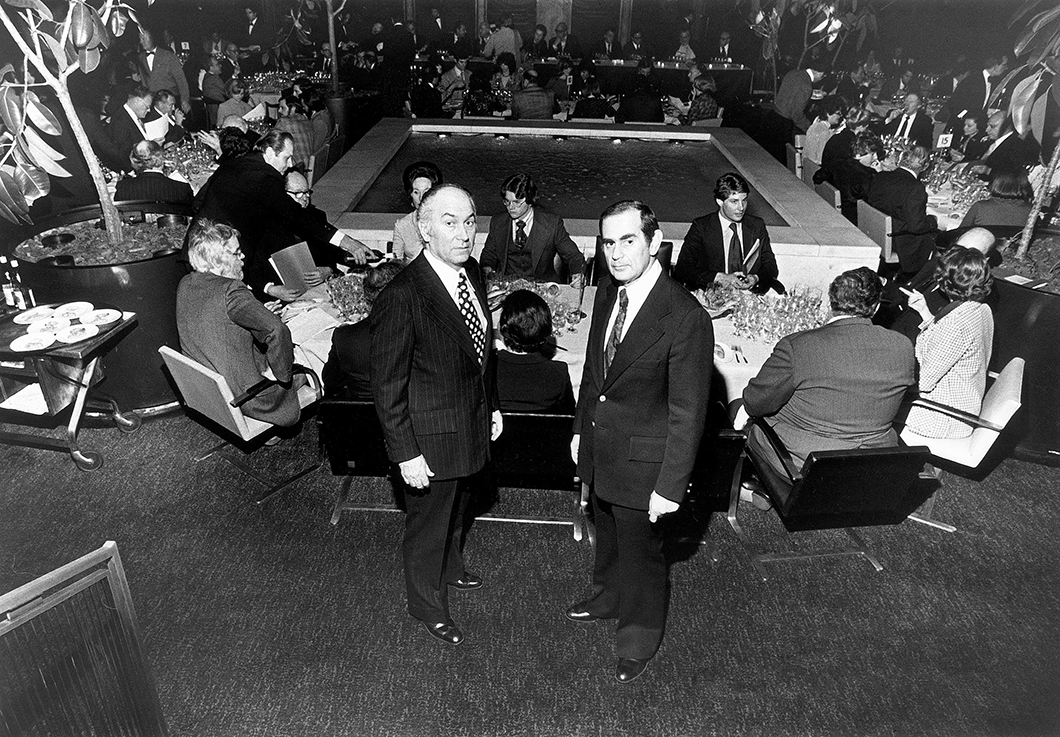

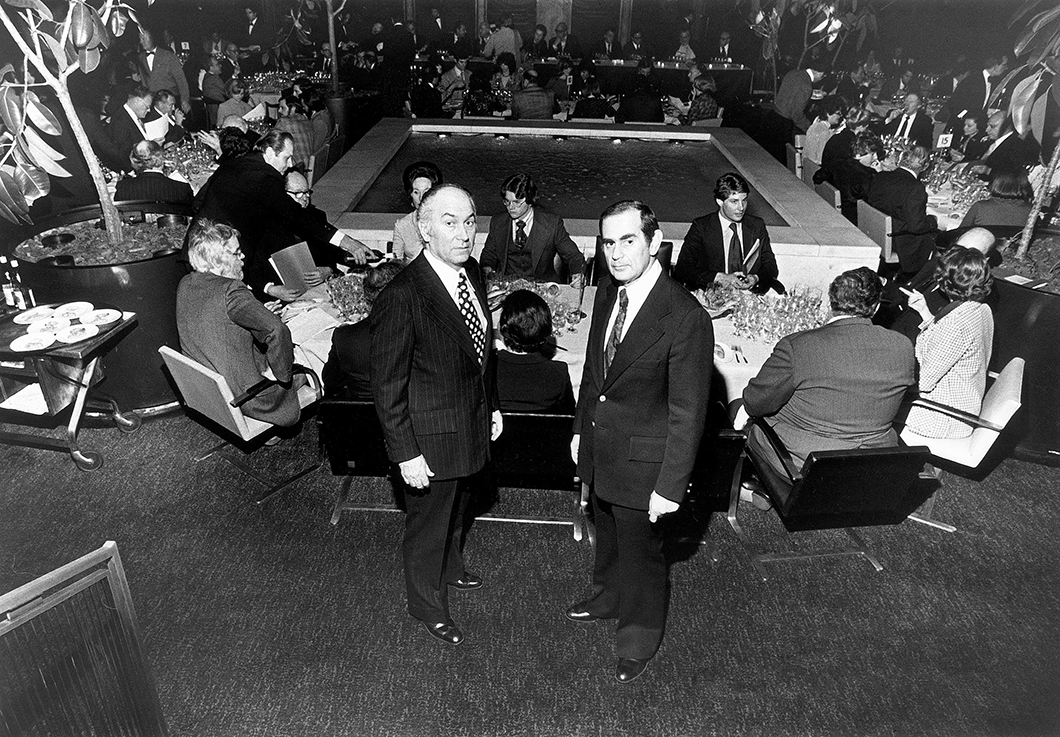

Former owners Paul Kovi and Tom Margittai in the Pool Room at The Four Seasons. Image courtesy of The Four Seasons.

Of working with Mies, Philip Johnson said, “No other important contemporary architect cares so much about placing furniture.” Johnson understood the full extent to which the restaurant formed an integral part of Mies' overall building design. "The thing about [Mies'] work is that it’s not a building—it’s an environment," Lambert told Nuovo magazine in 2007. "No one understood as well as he did that it’s about public and private space.” The restaurant was to contribute to this “environment” by providing a nexus point between the building's "public" plaza and the building's "private" interior.

“No other important contemporary architect cares so much about placing furniture.”

—Philip Johnson

Custom bronze-topped Saarinen Side Tables designed for The Four Seasons Restaurant. Image courtesy of Wright.

To furnish the Four Seasons Restaurant, Johnson worked closely with Florence Knoll—who had not long ago secured exclusive production rights for Mies’ collection housed in the Museum of Modern Art.

Johnson specified a number of custom-designed pieces for the restaurant interior. These included: l-shaped Florence Knoll Couches and Settees, bronze-topped Saarinen Side Tables, built-in banquettes, and Brno Chairs with padded armrests. According to Eric Larrabee, author of Knoll Design, it was Mies who suggested using the Brno Chair as the restaurant's primary seating.

Custom Brno Chairs designed for The Pool Room at The Four Seasons Restaurant. Image courtesy of Wright.

Following Mies’ lead, Johnson specified “a barstool in a Miesian-style,” to surround the perimeter of the Front Bar. Because no prior drawings exist in MoMA’s archive of Mies’ work, it is presumed that the resulting Four Seasons Stool was an on-site collaborative effort between Johnson and Mies for the special commission. The design was first produced for a wider market in 2004 by Carl Magnusson in Italy, before Knoll introduced a licensed version in 2006.

“The thing about [Mies’] work is that it’s not a building—it’s an environment.”

—Phyllis Lambert

Four Seasons Barstools surround The Front Bar at The Four Seasons Restaurant. Photograph by Jennifer Calais Smith.

For the restaurant's elevated level, Johnson selected Hans Wegner's PP-501 chair, which at the time was being distributed by Knoll. Restrooms and powder rooms included Eero Saarinen's Tulip Chairs, which Knoll had recently introduced. At each of the building's entries, Johnson created lounge areas of the Barcelona Chair, Stool, Couch and Coffee Table.

Tulip Armless Chairs furnish the powder room at The Four Seasons. Image courtesy of The Four Seasons.

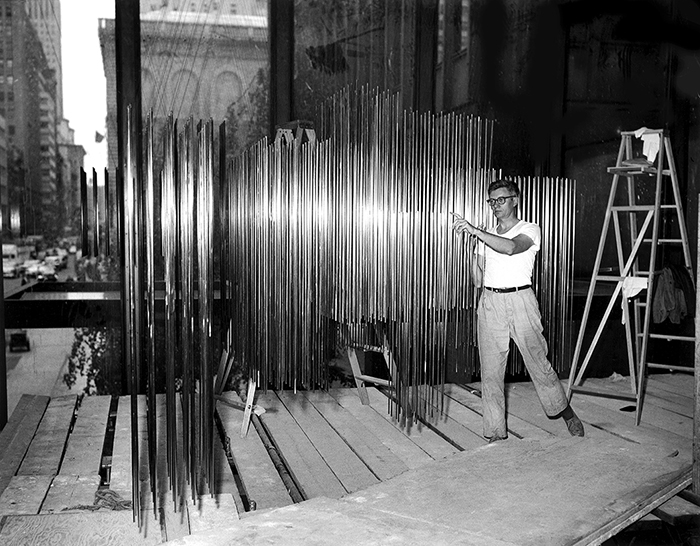

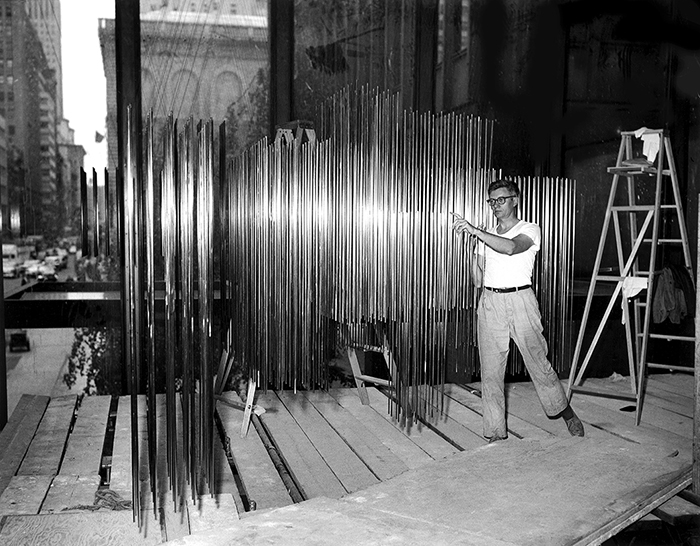

Lambert, Johnson and Mies also called in favors from the art world to furnish the restaurant. Pablo Picasso contributed the large curtain that forms a natural partition between the Grill Room and Pool Room; Picasso had originally created the piece for the Ballets Russes ballet Le Tricorne in 1919. Richard Lippold's major, now-iconic installation hangs suspended above the restaurant's Front Bar.

Not every artist was happy to oblige. Lambert asked Mark Rothko to create a series of panels for the restaurant. Soon after accepting the commission, he vented to a reporter that he had only done so out of spite, to “ruin the appetite of every [one] who ever eats in that room.” Rothko later decided to keep the paintings for himself.

“We must not try to solve new problems with traditional forms: it is far better to derive new forms from the essence, the very nature of new problems.”

—Mies van der Rohe

Sculptor Richard Lippold at work on his sculpture for The Four Seasons Restaurant. Image courtesy of The Four Seasons.

Since 1959, the restaurant has featured a rotating selection of artworks, complementing its permanent displays. These have included works by Joan Miró, Frank Stella, Ronnie Landfield, Robert Indiana and Richard Anuszkiewicz.

In its time, the completed interior was unlike any other dining experience in New York. Graydon Carter, editor-in-chief at Vanity Fair, described his first experience at the restaurant to New York Magazine: “The stark modernism of it threw me—I thought it was going to be like the Oak Room. And then, by the second time you go, you appreciate it. And then by the fifth time, you realize it’s the most beautiful restaurant in the world.”

All images are courtesy of Wright and The Four Seasons unless otherwise noted.