When asked how he arrived at Knoll, Richard “Dick” Schultz was at once jovial and candid: “That whole period in my life was so exciting because [up until then] I had gone in the completely the wrong direction.” That wrong direction turned into a decidedly successful career; Schultz’s designs for Knoll—notably the 1966 Collection, celebrating its 50th year—remain popular and contemporary to this day.

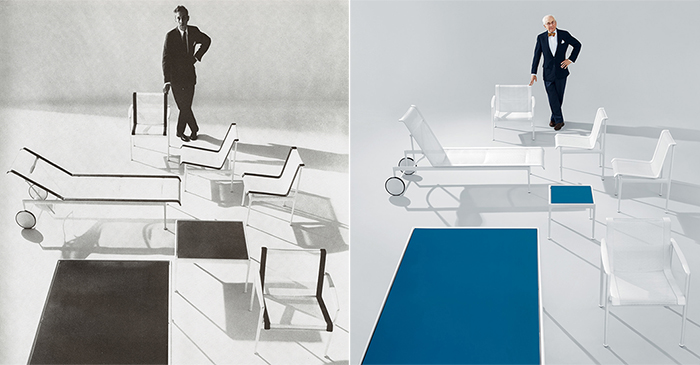

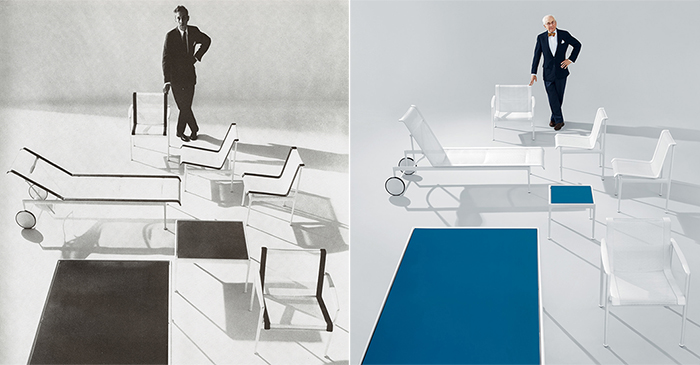

Left: Richard Schultz, 1966. Image from the Knoll Archive. Right: Richard Schultz, 2013. Photograph by Ilan Rubin.

A graduate of Iowa State University and the Illinois Institute of Technology, Schultz studied engineering and industrial design in school, neither of which were aligned with his true passion. “The thing that really intrigued me was furniture,” Schultz explained in an interview from 1977, “but there wasn’t any course of that kind. I was really excited by what was becoming available at that time, 1949-1950, after the war when everything started to move.” When Schultz first interviewed at Knoll, he showed Florence Knoll some sketches he had made on a recent trip to Europe during the summer. “These have nothing to do with furniture,” Shu remarked in her typically direct fashion, before asking, “What do you want to do?” Schultz replied, “I want to be a furniture designer.”

Original advertisement for The Leisure Collection, 1966. Image from the Knoll Archive.

So Schultz’s career began. His first, albeit brief experience was with the Knoll Planning Unit, the workplace interior planning department that Florence Knoll started in 1946. Schultz' self-evaluation revealed some shortcomings: “I wasn’t much good, I found it very difficult to stay at a desk,” he recalled. He was next assigned to help Harry Bertoia, Don Petitt and Bob Savage make the jigs and ancillary production equipment that the Bertoia Collection’s steel construction required. A formative time for the company and the young designer, Schultz considered “those years [1950-1952] more valuable than most of the schooling I’ve had.” If he has any regrets from that time, they are archival: “What I really regret is that we didn’t do more photography and documenting. Harry [Bertoia] couldn’t care less about all that. He worked all the time, we did too, because we weren’t married.”

“The thing that really intrigued me was furniture. I was really excited by what was becoming available at that time, 1949-1950, after the war when everything started to move.”

—Richard Schultz

The Leisure Collection shot at Beacon Hill Terrace, c. 1967. Image from the Knoll Archive.

At the time, Schultz was still developing a designer’s self-assurance. When the Bertoia Collection debuted in 1952, Schultz submitted his resignation, imagining he would never again be a part of something of equal interest or import. Knoll founder Hans Knoll, a skilled manager, asked: “Why don’t you come work in Europe for me? You know all about making the Bertoia chairs, you can go over there and make sure they know how to make Bertoia chairs in Europe.” Schultz obliged, and became something of a production supervisor for the nascent Knoll Europe.

Herbert Matter's graphic treatment of The Leisure Collection, 1966. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Schultz’s career at Knoll might have ended there. But one day in 1958, three years after Hans' untimely death, Schultz received an envelope from his former employer, Florence Knoll, who had recently retired to Florida. The envelope contained rusted bolts. The letter read: “Why can’t we make a chair that actually works?”

The brusque question, for those who knew how to read it, signaled an opportunity and a new frontier: outdoor furniture that would withstand the elements, season after season. It was a need that Florence Knoll, a resident of Florida, understood all too well. And so Schultz began a correspondence with Florence about the effects of the corrosive sea air on the company’s furniture.

“Most outdoor furniture in those days was designed to look as if it was designed before the French Revolution.”

—Richard Schultz

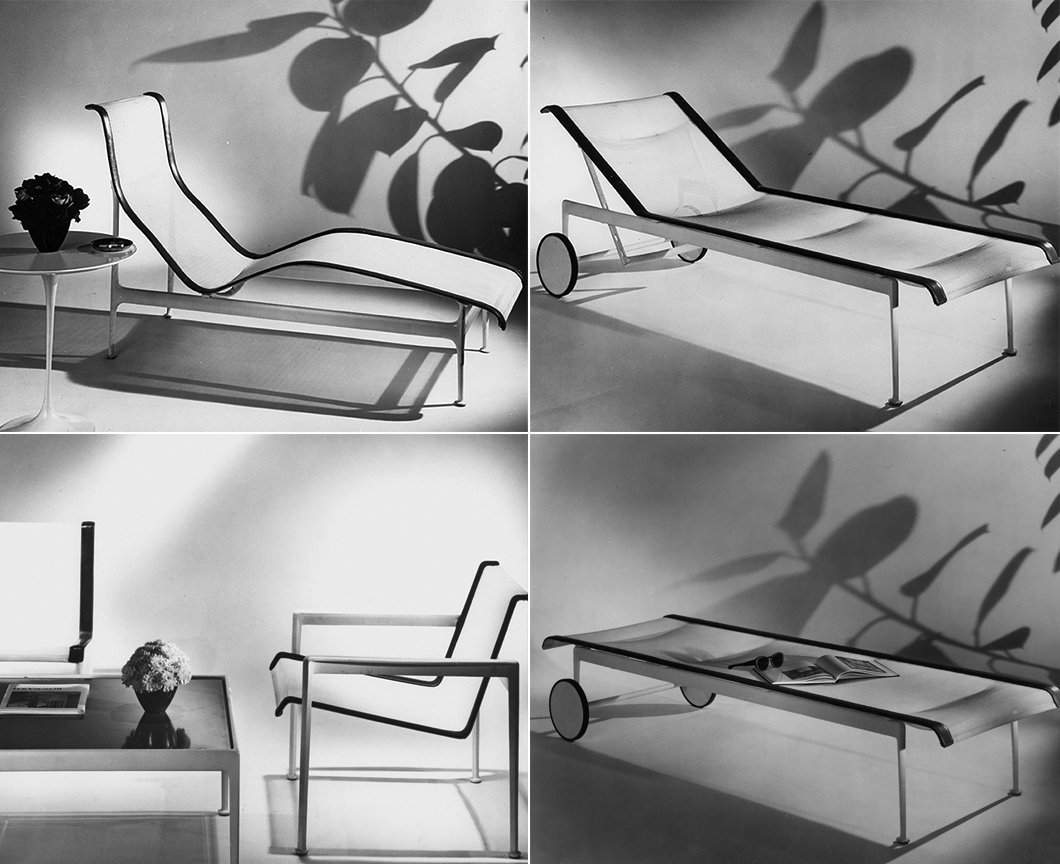

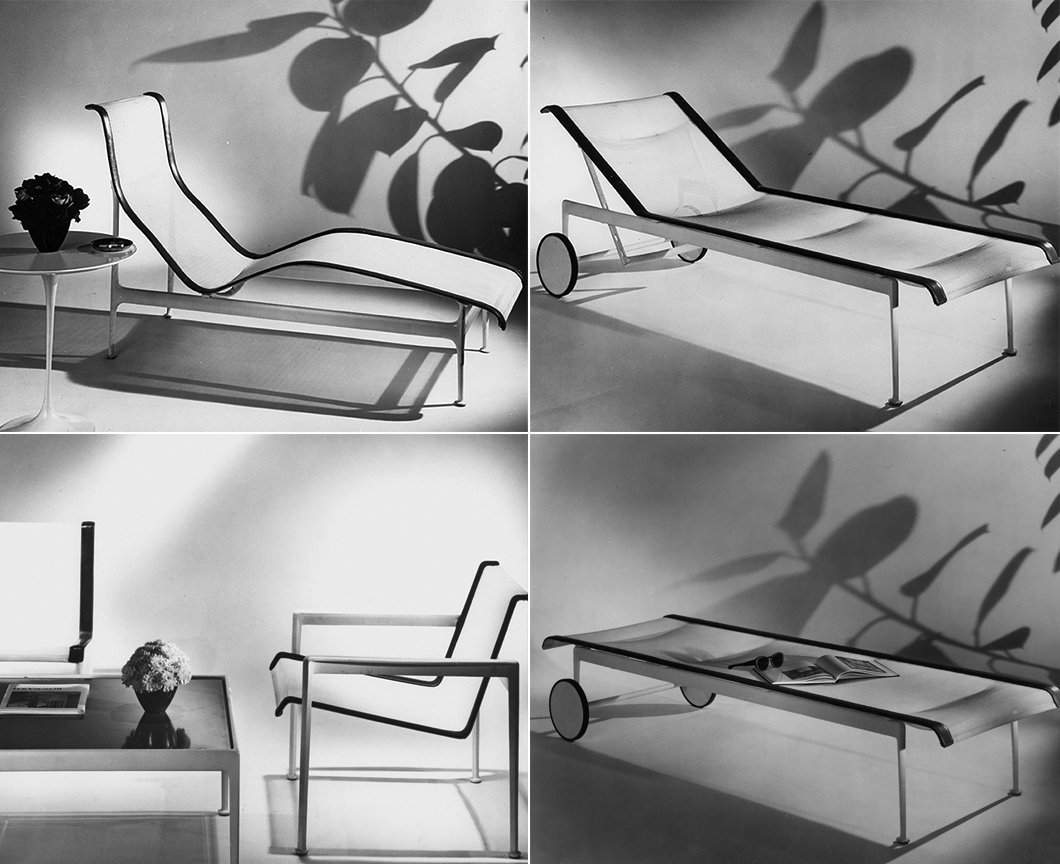

The Leisure Collection by Richard Schultz, 1966. Image from the Knoll Archive.

By 1962, Schultz had begun to develop an outdoor line of patio furniture, intended to be both practical and aesthetic. “Most outdoor furniture in those days was designed to look as if it was designed before the French Revolution,” Schultz explained of the cultural context, “with stamped-out metal, bunches of flowers and leaves.” (Schultz’s Topiary™ additions to The Leisure Collection are an homage to this expectation.)

Clockwise: 1966 Contour Chaise, 1966 Adjustable Chaise (upright), 1966 Adjustable Chaise (reclined), 1966 Lounge Chair and Coffee Table.

Already field-tested in the company’s production methods, Schultz began to research durable, weather-resistant materials. Of his process, Schultz reflected, “My training was very non-professional […] so it was all work with materials and tools.” This hands-on approach was familiar to him, recalling his early days in design school. “We used to go over to the Knoll showrooom as students and turn the chairs over and look at them,” he said. Back then, Schultz was playing catch-up, trying to ascertain how his design mentors created their pieces. Now, Schultz was the one doing the innovating.

“It took me a long time to develop the collection, as there wasn’t a whole team of people to help me.”

—Richard Schultz

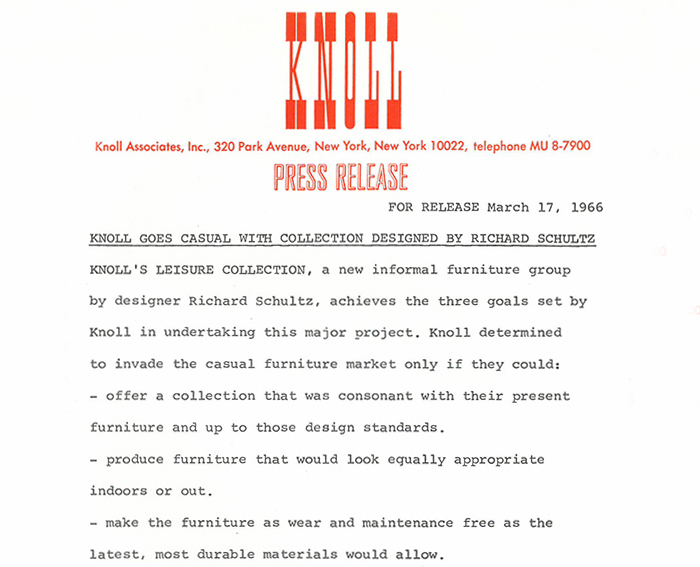

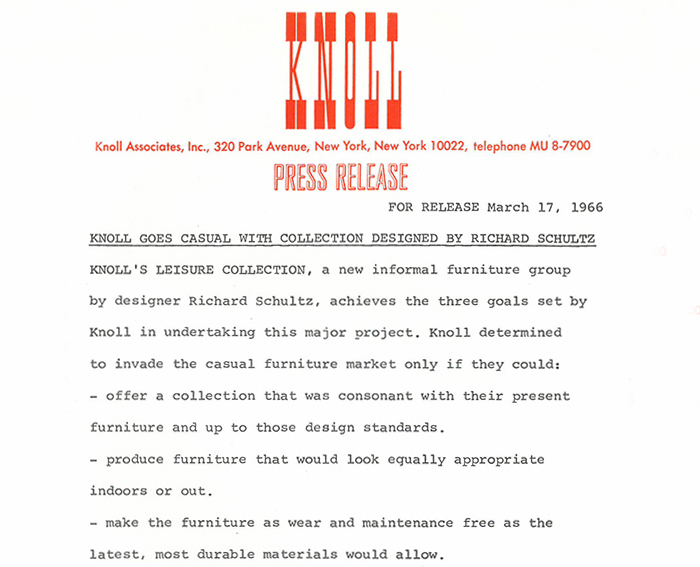

Original press release for The Leisure Collection, 1966. Image from the Knoll Archive.

As with the Bertoia jigs, what would become the 1966 Collection was the result of a small team effort, and long hours. Schultz remembered, “It took me a long time to develop the collection, [since] there wasn’t a whole team of people to help me.”

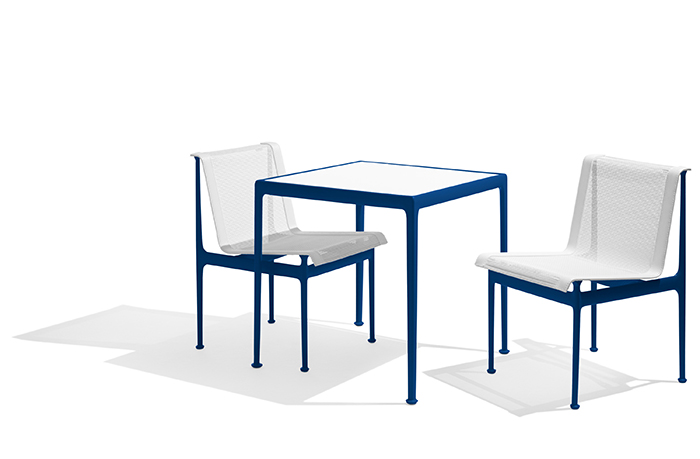

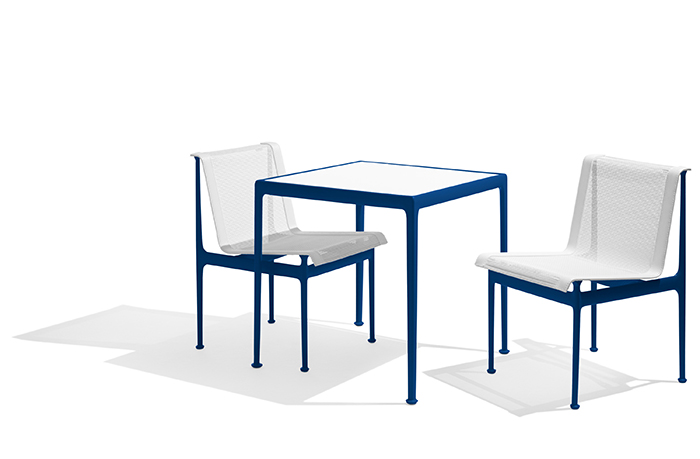

The 1966 Collection by Richard Schultz. Image by Knoll.

Schultz soon realized that what the industry was then calling “outdoor furniture” was actually nothing of the sort—the iron and steel structures and protective coatings were prone to corrosion. What’s more, the industry was not testing the furniture’s performance over long enough time periods. Schultz thought he could do better.

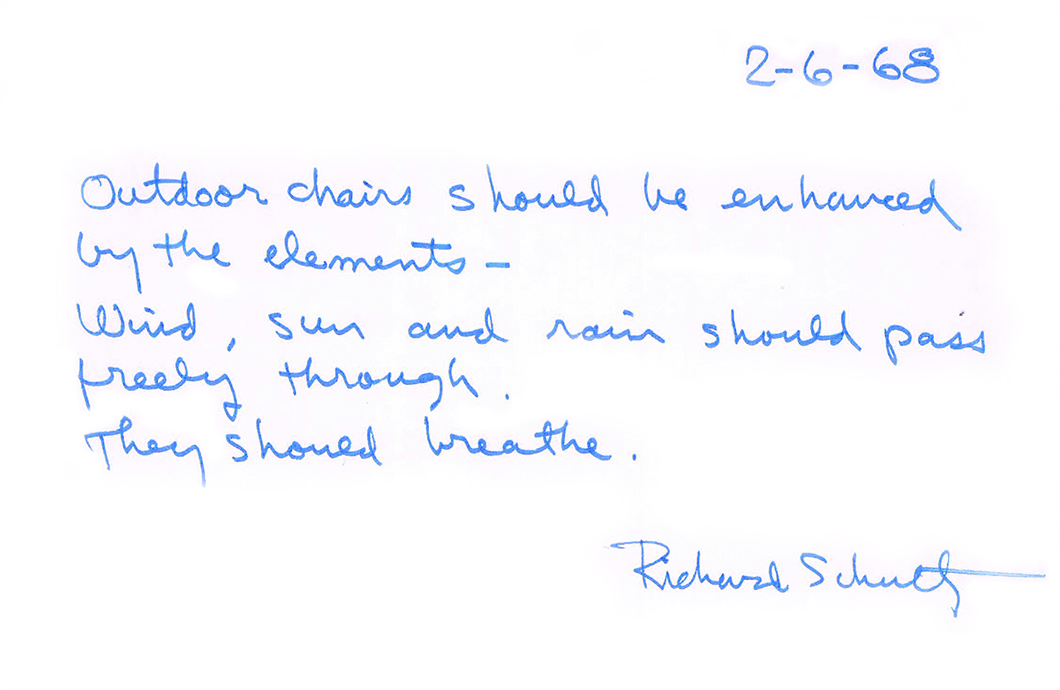

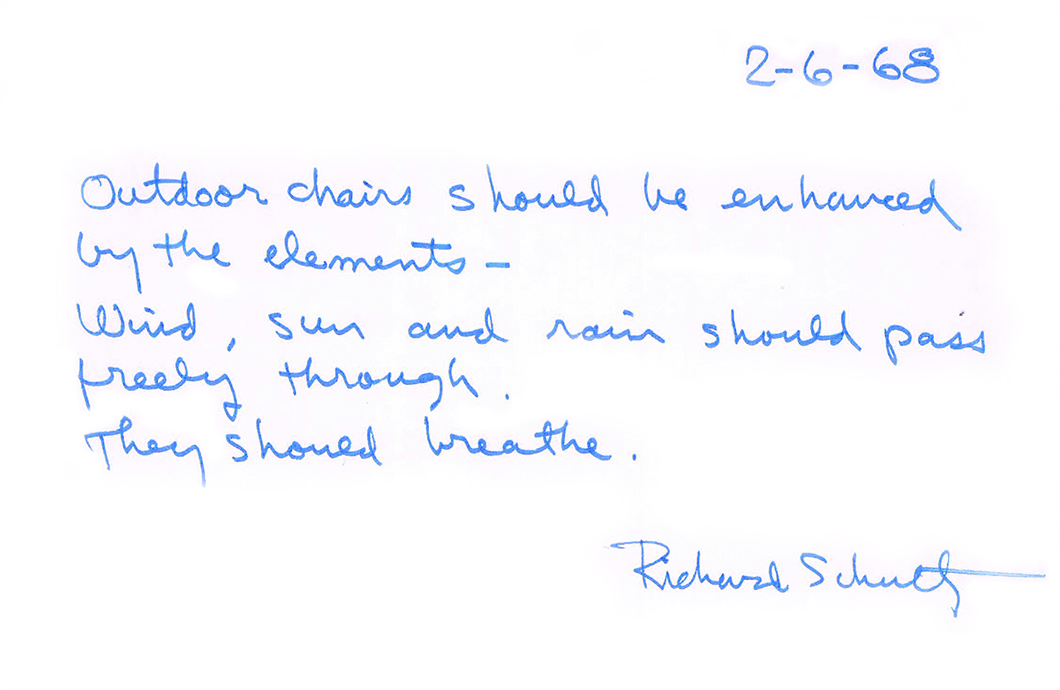

“Outdoor chairs should be enhanced by the elements—wind, sun and rain should pass freely through. They should breathe.”

—Richard Schultz

The Leisure Collection, 1969. Photograph by Jon Naar. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Like all design, the 1966 Collection came about through countless iterations. Eventually, Schultz arrived at a rough frame—what he called a “mule”—made of copper tubing. The team improved upon this initial version with seamless aluminum castings. The frames were then coated with multiple layers of plastic paint that was specifically designed to be both maintenance-free and rust-proof. For the chairs, Schultz chose nylon-Dacron. It had all the qualities Schultz desired in a fabric: cool-to-the-touch, quick-drying and porous. With little in the way of extraneous style, Schultz added a colored vinyl strip along the chairs edge. This hid the unseemly connections and afforded an opportunity for restrained customization.

Knoll International brochure for The Leisure Collection, 1969. Photograph by Jon Naar. Image from the Knoll Archive.

At first, the chairs were only available in white, red-orange, yellow, blue or brown. Since, these choices have expanded to include Onyx, Lime Green, Green and Plum.

“We spent so much time refining it, that’s why the furniture still looks fresh.”

—Richard Schultz

One of the newly revised colorways available for the 1966 Collection. Image by Knoll.

To accompany the seating, Schultz designed a series of tables. The inset table tops are made of porcelain enamel, designed to drain pools of water that may accumulate. Such details were carefully considered. “We spent so much time refining it,” Schultz recalled, “that’s why the furniture still looks fresh.”

An excerpt from a letter by Richard Schultz, 1968. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Launched on March 17, 1966, The Leisure Collection—now called the 1966 Collection—was “a breath of fresh air” for fans of modern design. Schultz had successfully upended the paradigm for patio furniture by positing that rather than weather the elements, “outdoor chairs should be enhanced by [them]—wind, sun and rain should pass freely through. They should breathe.” And breathe they do, fifty years later.