Rotterdam Renewal

Exploring the restoration project that won the 2016 World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize

Arjan Hebly first discovered the Justus van Effen complex on a field trip in 1977, while he was a student at the Delft Faculty of Architecture. “Sometimes architecture knocks you sideways,” he later wrote, “and this was one such occasion.”

Located in the Spangen neighborhood of Rotterdam, a residential area initially developed for the city’s port workers, the complex was designed by Dutch architect Michiel Brinkman in 1922, becoming what Hebly called “the apotheosis of Dutch functionalism.” Brinkman was an experienced architect of factories, offices, and warehouses in the early twentieth century, so when commissioned by the Municipal Housing Authority to design a social housing project with 264 units, he borrowed certain organizing principles from his past work.

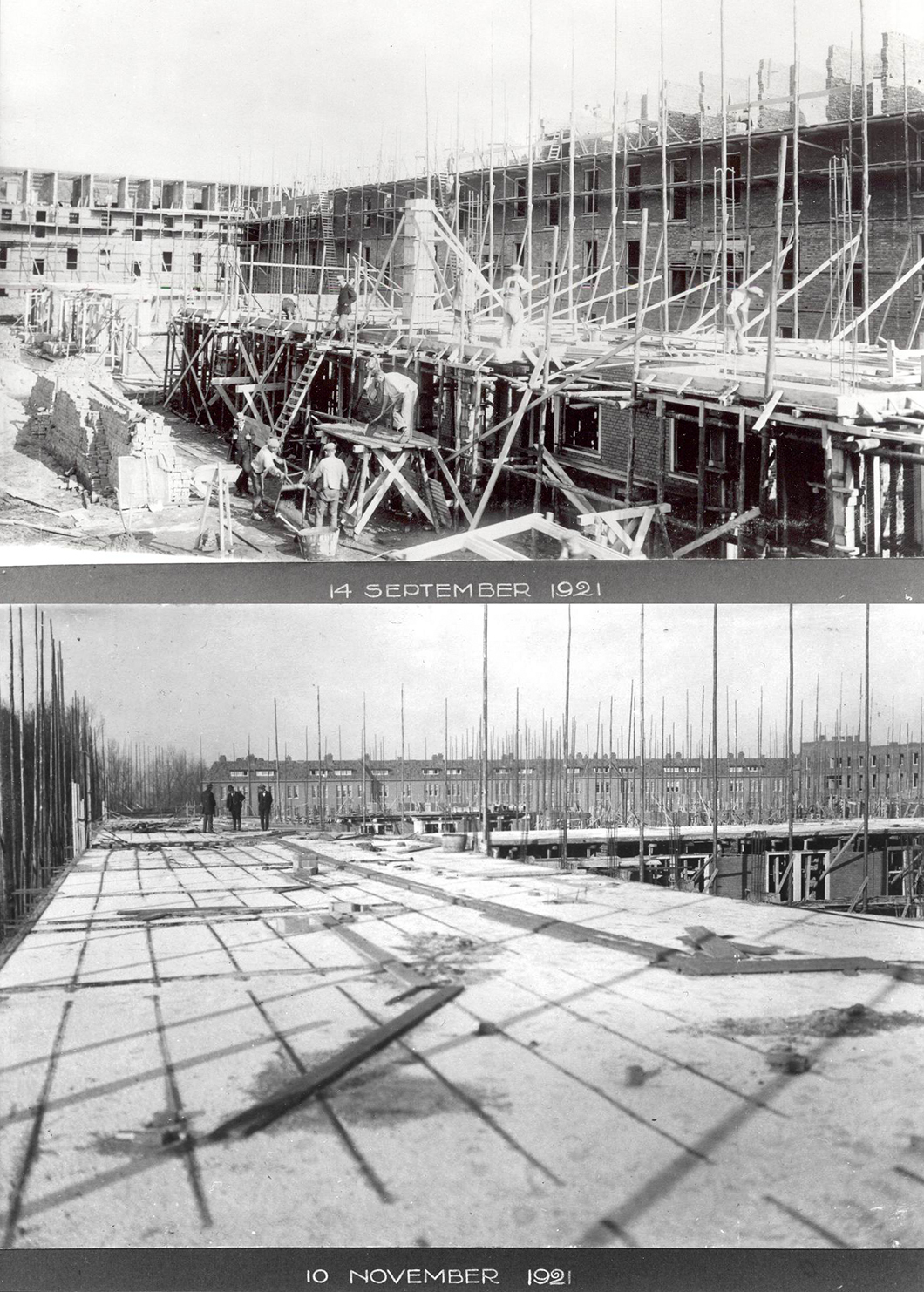

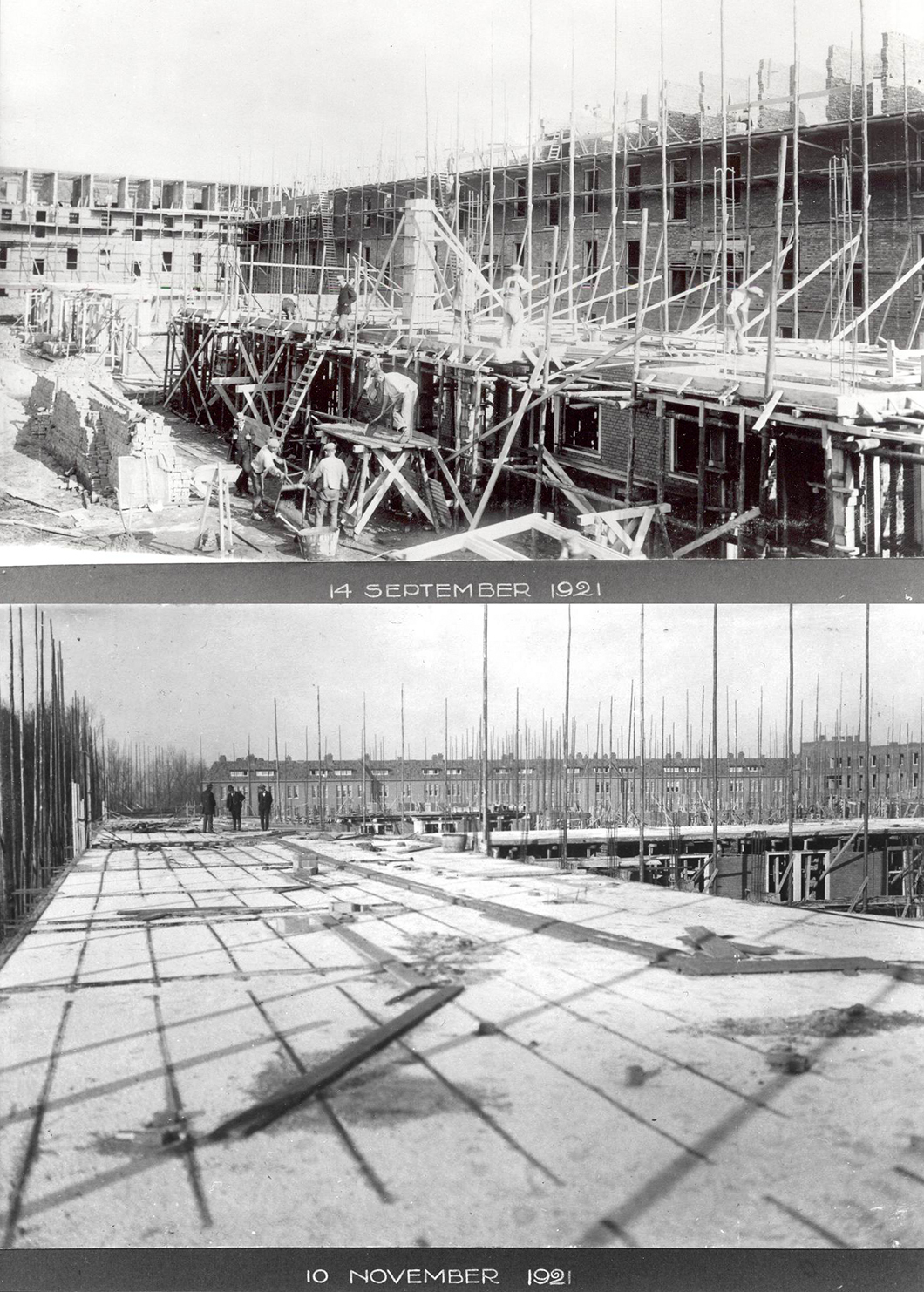

The Justus van Effen Complex, with its 'street in the air' during construction. Photographs courtesy of Molenaar & Co. architecten.

“Sometimes architecture knocks you sideways, and this was one such occasion.”

—Arjan Hebly

“In [Brinkman’s] design for the flour factory along Maashaven, the focus had to be on the logistic processes of supply, transport and storage of raw materials, finished products and energy as well as the organization of the production process,” Hebly explains. In the few drawings of the Justus van Effen complex that remain, Brinkman similarly indicated the anticipated delivery routes of milkmen and local bakers and sketched out flows of garbage collection, energy supply, and foot traffic.

The linchpin of Brinkman’s design, and what makes his intended patterns of circulation possible, is a wide, raised gallery that wraps each housing block and ties the entire complex together. The so-called ‘street in the air’ was a remarkably direct and effective solution to questions of social cohesion in public housing, and it inspired similar schemes in later projects during the post-war period, both in the Netherlands and abroad.

The Justus van Effen Complex in 1924. Photograph courtesy of Molenaar & Co. architecten.

“As an answer to faceless urban architecture, Brinkman sought to achieve a feeling of unity associated with garden-village development, whilst using a stacked construction.”

—Joris Molenaar

The unique logistical emphasis of Brinkman’s design, along with the subtle beauty of its structural details, made it the focus of a recent competition to restore the entire site to its original splendor, following an unsuccessful renovation in the 1980s. In this early attempt at restoring the complex, the courtyard façades were painted white and became discolored within a couple of years, the brickwork in the stairwells were hidden beneath tiles, and the windows were fitted with basic aluminum frames. It was during these years that the Spangen neighborhood became increasingly run-down and crime-ridden.

Led by Dutch architecture practices Molenaar & Co. and Hebly Theunissen, alongside Amsterdam-based landscape architect Michael van Gessel, the second preservation effort began in 2006 and was completed in 2012. The result, a more sensitive rehabilitation of the original site that in turn spurred the renewal of the Spangen neighborhood, was awarded the fifth citation of the World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize in 2016.

Even today, the complex is rare in its offering of a middle ground between two conventional models of social housing: the poorly ventilated, dimly lit towers of dense cities and the undifferentiated row houses of suburban enclaves. “As an answer to faceless urban architecture, Brinkman sought to achieve a feeling of unity associated with garden-village development, whilst using a stacked construction,” architect Joris Molenaar writes in a monograph on Brinkman and his practice. “The plan also signified a step in the direction of economical, efficient residential housing, through the deployment of central staircases and central facilities to reduce the amount of space and materials needed.”

The Justus van Effen Complex, with its raised gallery, restored in 2012. Photograph courtesy of Molenaar & Co. architecten / Bas Kooij.

To fulfill his goal of improving the well-being of the buildings’ users, Brinkman turned to the rich possibilities of new construction methods. Tapping into the growing popularity of reinforced concrete, the architect used the material to build the stairs, the raised gallery, the balustrades, and the modern central burner under the bathhouse. “It was fitting for a time in which modern technology ruled every building, to strive toward the nth degree of beauty by applying such technology in unadulterated form,” August Plate, the director of the Municipal Housing Service who commissioned the project, recalled. “This meant the further jettisoning of everything that had been retained in the construction process up to then as heirlooms from obsolete styles.”

“It was fitting for a time in which modern technology ruled every building, to strive toward the nth degree of beauty by applying such technology in unadulterated form.”

—August Plate

The considerate design of the Justus van Effen Complex, enabled by technological innovation, trickles into all its smaller components. “At every level, every detail of the complex’s design was thoroughly thought out, both functionally and aesthetically,” explains Molenaar. “It provided for a central burner with a radiator in each flat, a refuse chute from every kitchen and a collective bathing and washing facility in a central bathhouse.”

The Justus van Effen Complex in 2005 and 2016, before and after the most recent renovation. Photographs courtesy of Molenaar & Co. architecten / Bas Kooij and Hebly Theunissen architecten.

In the most recent renovation by the winning team, both the logic and details of the Justus van Effen complex were celebrated and refreshed. “By working on this task of restoration, the amazement about the beauty and the ingenious qualities of the project only grew,” Hebly told Knoll. “The original design was worked out on all levels, on all scales, so cleverly, in all the dwellings Michiel Brinkman designed.”

“For instance, the windows are so very well-shaped and situated from both the inside as the outside, and these are thrilling things to discover. And in our work on the monument, we increasingly grew to the conclusion that we had just to follow this original beauty and logic. By doing that, everything fell on the right spot, as it seems.”

“In our work on the monument, we increasingly grew to the conclusion that we had just to follow this original beauty and logic. By doing that, everything fell on the right spot, as it seems.”

—Arjan Hebly

The varied openings on the façades of the Justus van Effen Complex are indicative of the interior layout. Photograph courtesy of Molenaar & Co. architecten / Bas Kooij.

While the windows on each building were specially sized to indicate the functions of the rooms—larger, horizontal windows for the living rooms and smaller, recessed windows in the bedrooms, for example—the arrangement of the building blocks resulted in a sequenced layout of public spaces.

“The configuration of the strips of buildings yields a multitude of different spatial forms,” Hebly writes, “from street space to small, medium, and large courtyards connected by a well-thought out system of architecturally differentiated gates and openings between the strips of buildings.”

“The configuration of the strips of buildings yields a multitude of different spatial forms.”

—Arjan Hebly

The building arrangement in the Justus van Effen Complex results in a sequence of differentiated public spaces. Photograph courtesy of Molenaar & Co. architecten / Bas Kooij.

From the ornamental tiling of the yellow brick to the plant boxes and tiled mosaics of the elevated walkway, the flourishes of the Justus van Effen Complex are understated, but not overlooked. The residential volumes include apartments of various types and sizes: from single-floor apartments to maisonettes to a few larger four-storey units. The apartment buildings all wrap around a bathhouse in the middle of the complex, which has now been converted to a gallery and reception space.

Apart from restoring the project to its original design, the architects also introduced contemporary amenities to the residential dwellings. “Of course, we also did new things like installing and integrating a new central and sustainable heating system in the dwellings with the use of thermal heat, new interior elements with glazed doors, to let the light and space do the main job in the houses,” Hebly told Knoll. The roof of the complex is covered in solar panels, generating heat for tap water.

“We also did new things like installing and integrating a new central and sustainable heating system in the dwellings with the use of thermal heat, new interior elements with glazed doors, to let the light and space do the main job in the houses.”

—Arjan Hebly

The residential spaces of the Justus van Effen Complex and the converted central bathhouse. Photographs courtesy of Molenaar & Co. architecten / Bas Kooij.

The interiors of the apartments have been painted a gleaming white and the stairwells have been restored to their original brickwork. The green spaces of the Justus van Effen Complex involve elevated grass surfaces and solitary trees, inviting residents to come together and use the outdoor spaces. But despite every improved amenity, Hebly insists that the true charm of the complex lies in its ineffable qualities, the ones that elude measurements and photographs. “Ultimately, he writes, “architecture as penetrating as this is about inarticulate understanding.”

“Ultimately, architecture as penetrating as this is about inarticulate understanding.”

—Arjan Hebly

Subtle ornament on the façades of the Justus van Effen Complex. Photographs courtesy of Molenaar & Co. architecten / Bas Kooij.

The winners of the World Monuments Fund / Knoll Modernism Prize will present their work on the restoration of the Justus van Effen Complex in a public presentation at the Museum of Modern Art on Monday, December 5, 2016.