There’s a moment that many of us have been playing over and over in our heads since the pandemic started. It’s simple: we walk up to our favorite café/museum/restaurant and see a friendly face. We take a seat and catch up, talking about everything and nothing inbetween. It doesn’t matter. We’ve ached for this very basic type of interaction, connecting with another human being.

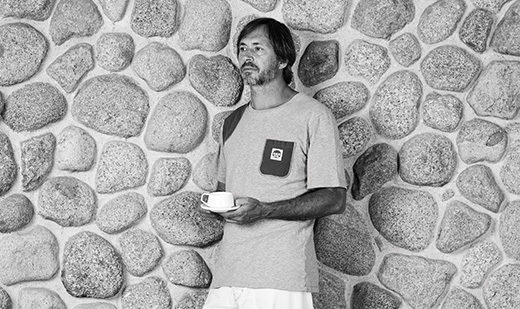

Now, this type of interaction can happen in many types of spaces on many types of furniture in many types of ways. But a pair of chairs is its simplest expression. And designer Ini Archibong knows something about the way furniture can help connect.

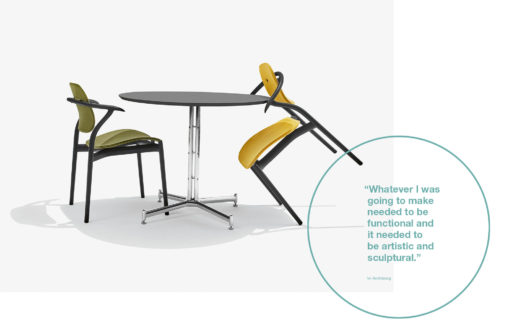

“A chair in general already implies interaction,” Archibong says. “When you see a chair like [his recently launched Iquo chair], you aren’t thinking about sitting alone. You see two chairs usually—it automatically implies interaction and dialogue.”

The Iquo Café Collection, launched in 2022, fosters just this type of interaction and dialogue. Archibong designed it for spaces that expand and contract, accommodating a duo or a large group thanks to chairs that stack neatly and tables with a tidy pedestal base. “They can be ganged up in a row, like a big dining table. You can keep expanding and make the space bigger and bigger,” he says.

The chair feels wholly Ini Archibong, starting with its moniker—his grandmother, mother, and daughter all share the name Iquo—and carrying into its form. The inspiration for the name, and the female influence—including that of what he calls “an army of aunts”—in his designs is apparent. “I think a lot of people that like my work would say there’s a bit of a feminine quality to it. In nature—you see a lot of elegant structures out there are also strong.”

Archibong was raised in Pasadena, California by Nigerian immigrant parents who were scholars and scientists (his mom a computer scientist and his dad an engineer), later complementing this with art school and an immersion into the design world. This dual perspective serves him well, allowing him a universal expression and almost objective approach to solving problems.

He worked closely with Knoll and the team of engineers to design the chair to be as practical as it is beautiful, understanding the nuances that go into designing for people with a wide range of needs and the BIFMA testing that is required. “Not only was it going to be a beautiful and elegant object that people would want to look at, but that it filled all of those needs,” he says.

That importance placed on this style of total design feels especially apt for Knoll: “What separated Knoll was an appreciation of art and engineering, to take people who are artists in the first place and put them in a situation where they were creating furniture for a lot of people,” he says. “Whatever I was going to make needed to be functional and it needed to be artistic and sculptural.

Archibong’s unique background lends him to consider it all. He received a degree in environmental design from Polytechnic School and the Art Center College of Design and furthered his studies in Switzerland (where he currently resides) at the École cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL), earning a master’s in luxury design and craftsmanship. In 2021, he was one of many contemporary artists featured at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in “Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room.” That same year, he installed the “Pavilion of the African Diaspora” as part of the London Design Biennale, where he was awarded the Best Design Medal. And he has collaborated with venerable brands such as Hermès, Logitech, Bernhardt, and Sé. In each discipline and with each collaboration, he knows his audience. “The people using these spaces don’t need to be confused about whether it’s a chair or a garden sculpture,” he says, grinning.

He takes inspiration from any- and everything, allowing one detail or element to manifest itself in different ways, in a variety of projects. “I haven’t found anything I can’t design and because of that, I appreciate the nuances of a lot of different things,” he says. “That turns me into a big collector.”

And he uses his inspiration to approach any design project the same way: “The overriding elements of the form and form language are the same to me. I work across mediums, I don’t separate things ... so if I’m creating fork, it’s same as a building—you’re consuming it and you’re feeling the nuances of it. You see the entire thing.”

Photography by Uzo Oleh, Andrea Ferrari, Drapeau Noir, and Ilan Rubin

More to Read

This story is from Knoll Works—our annual publication showcasing how our design and spatial planning approach helps create places people love to be.