On May 24, 2017, Florence Knoll Bassett—known throughout her life by her friends as "Shu"—turns 100 years old.

This is her story.

1917: Early Years

Florence Margaret Schust was born to a baker in Saginaw, Michigan in 1917. Her rise to the top of the design world began in tragedy, when she was orphaned at age 12.

Fortuitously, her guardian brought her on a tour of possible boarding schools, among them the recently opened Kingswood School for Girls in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. The school was designed by Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen; at the time, he was also headmaster of the Cranbrook Academy of Art.

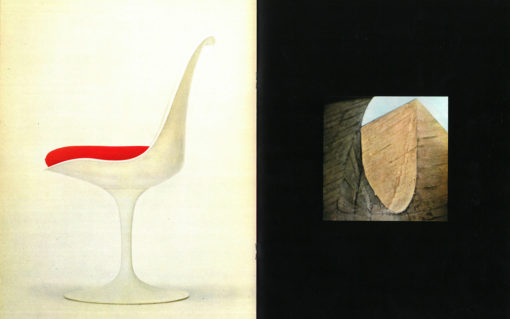

At Kingswood, Florence Knoll developed an interest in architecture and caught Eliel Saarinen's attention. Over time, she became an extended part of the Saarinen family, which included Eliel's son Eero Saarinen, who would go on to become a distinguished architect. Shu and Eero became lifelong friends and she would later commission him to design a collection of groundbreaking furniture for Knoll.

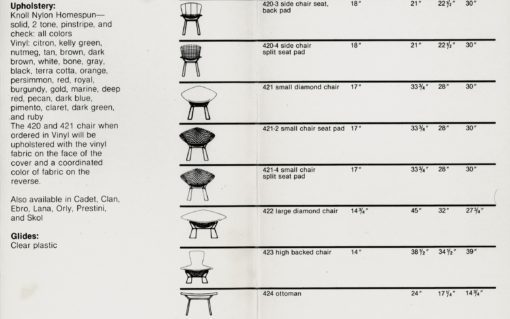

Upon graduating from Kingswood, Florence enrolled at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, the beginning of her years of serious design training. There, she met Harry Bertoia, who would also eventually collaborate with Knoll on modern furniture designs.

Florence Knoll went on to study at the Architectural Association in London, but the outbreak of World War II brought her back to the United States, and she completed her formal training at what is now the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago.

During these formative years, Florence Knoll met many of the leading architects of the time, including Alvar Aalto, Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Some of these early mentors would come to figure prominently in her future work at Knoll, but it was Mies who had perhaps the clearest influence on her signature approach to design: rigorous and methodical.

1941: Knoll Associates

Aiming to pursue work in architecture, Florence moved to New York City and there met Hans Knoll.

Hans Knoll was the third generation of a Stuttgart-based furniture manufacturing family, and he sought to bring European Modernism to a new audience in the United States.

The pair began working together, and soon Florence Knoll was taking an increasingly significant role in the company’s aesthetic development, in addition to her official role designing office interiors.

Before long the two were business partners, and in 1946 the pair married, renaming the company Knoll Associates.

Florence Knoll soon became inextricable from the company's advances in the industry.

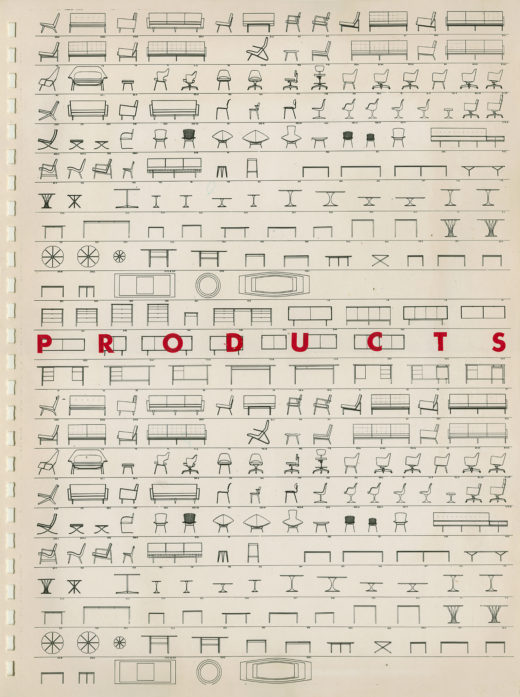

She broadened the company’s existing array of furniture offerings to eventually include the work of some of her Cranbrook colleagues as well as the prominent Modernist figures who had influenced her critical eye. These pieces became iconic of the corporate interiors of the post-war period and remain timeless designs to this day.

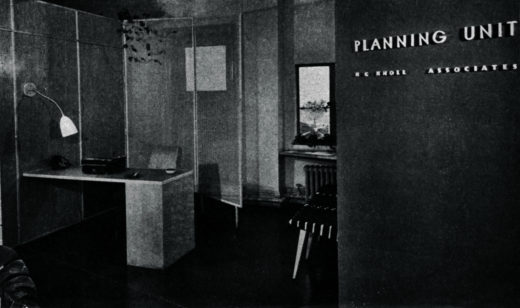

1945: The Planning Unit

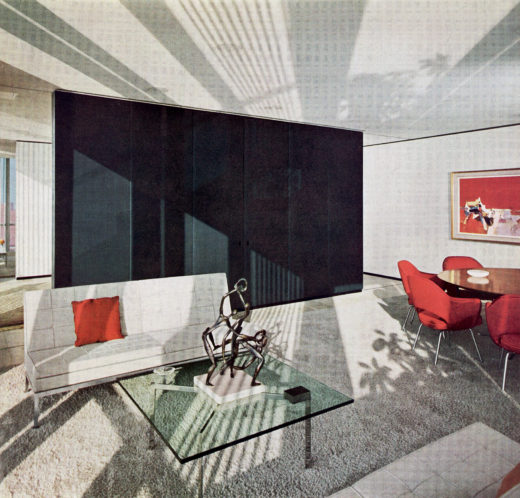

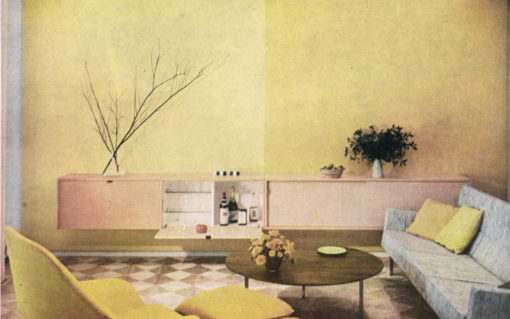

In 1945, Florence Knoll established the Knoll Planning Unit, an interior design division of the furniture company that set the standard for the mid-century modern interior.

“The Planning Unit began when I joined Hans Knoll at 601 Madison,” recalled Florence Knoll.

“As the projects grew, three or four designers were hired. In spite of the size of some of the projects like Connecticut General, the group never exceeded six to eight designers. We somehow managed to get the job done and on time. I don’t think I could have worked with a larger group. Peter Andes, a PU member, called it 'Shu U' as other young designers were siphoned off by architectural firms who began to start their own interior design divisions.”

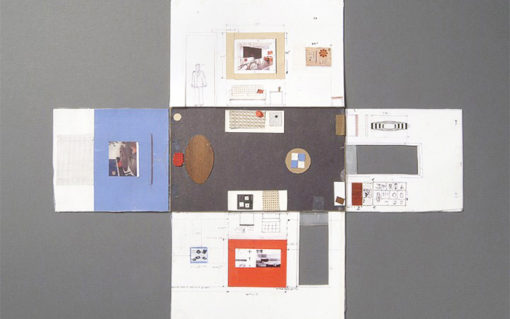

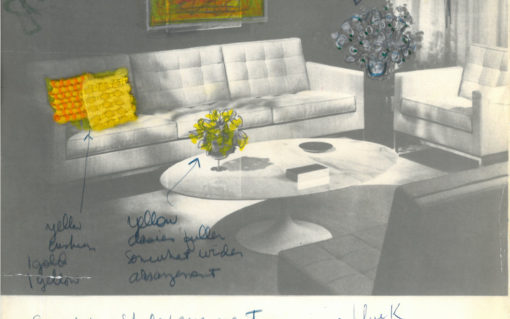

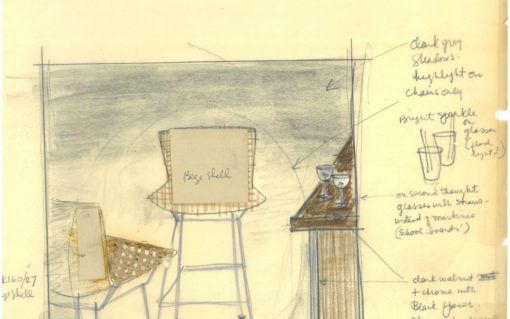

Florence Knoll’s meticulous methods of assessing a client’s needs and patterns of use were clear in her sketches, annotations, and especially the "paste-up" cardboard models she used to demonstrate envisioned spaces.

A unique visual planning technique, her paste-ups would feature folding walls, drawings of the furniture and fabric samples of the upholstery, all accompanied by detailed notes.

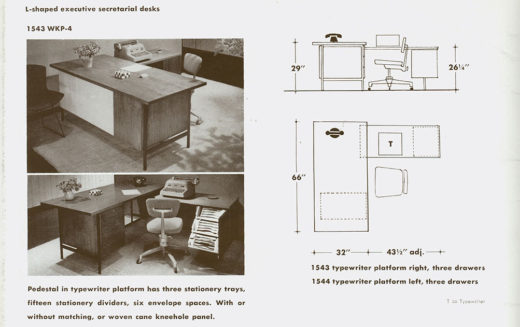

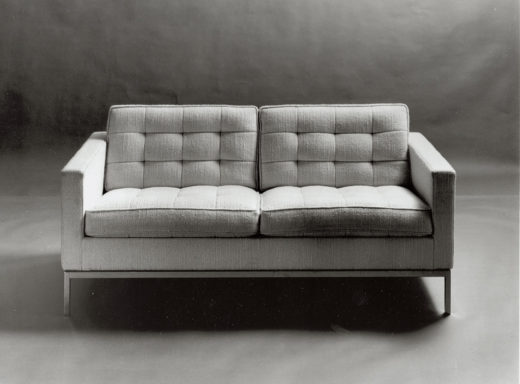

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Florence Knoll also designed individual pieces of furniture—foils to the more sculptural designs she commissioned with her exacting taste from the likes of Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Isamu Noguchi and George Nakashima.

Responding to direct needs encountered while working on projects and finding the market lacking, Florence Knoll designed seating, tables and case goods. Over the years, Florence Knoll designs, which she had conceived as background architecture, have proven to be design classics all their own.

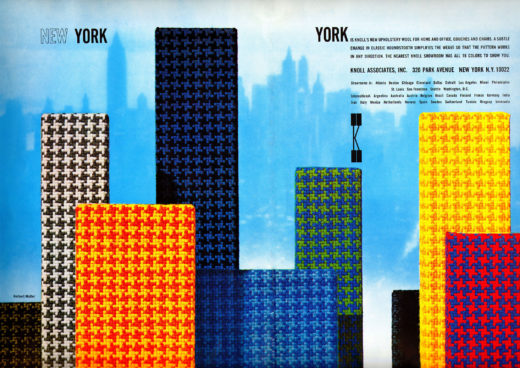

1947: KnollTextiles

In 1947, Florence Knoll launched a textile program to fill another gap she perceived in the market for contract furniture upholstery. This would later become KnollTextiles.

"It became apparent to me that suitable textiles were not available for our furniture and interiors," Shu wrote.

A separate Knoll showroom devoted entirely to textiles opened on East 65th Street, initially including fabrics intended for men's suiting sourced from Shu's time at the Architectural Association in London. Eventually, KnollTextiles would develop several signature fabrics that set the benchmark for the contract market.

Shu's use of small fabric swatches—the simple but effective practice of stapling fabric samples to pieces of carboard—in client presentations led her to develop a tagged sample and display system that eventually became an industry standard.

Working with Swiss photographer and graphic designer Herbert Matter on the Knoll showroom at 601 Madison Avenue, Shu developed a gridded textile "wall" and fabric "tree" as methods of presentation that eventually became widespread across Knoll showrooms and those of Knoll’s competitors.

1950s: Graphics & Showrooms

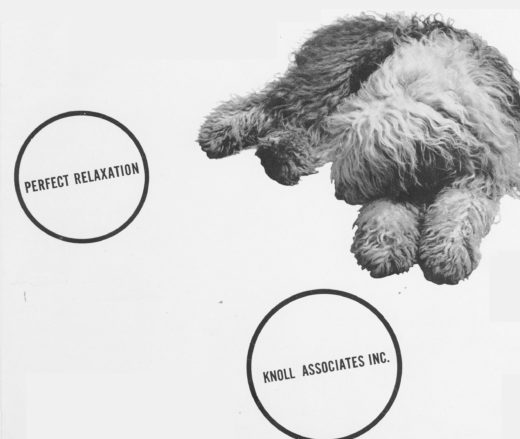

Under Florence Knoll's stewardship, the company also developed a distinctive graphic identity, collaborating with Herbert Matter to design everything from advertisements and stationery to the company’s distinctive logo.

Her influence on the "total design" sensibility of Knoll cannot be overstated.

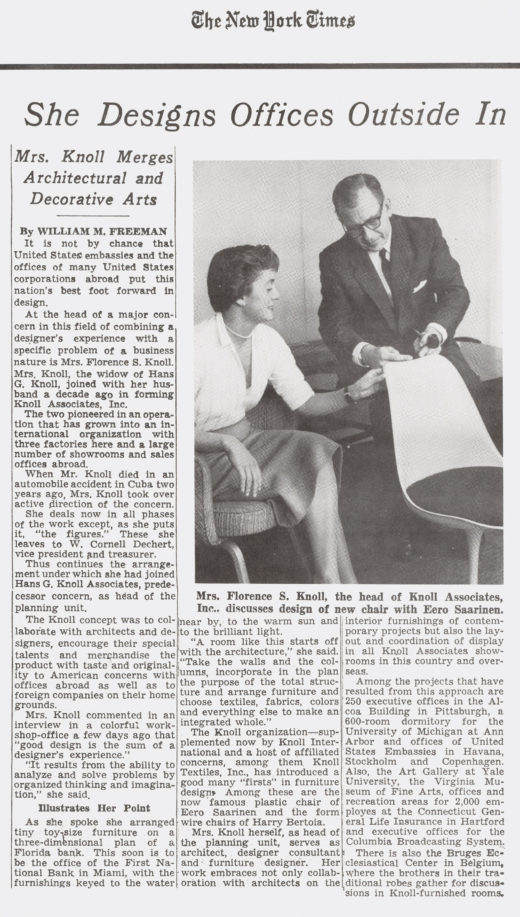

But in 1955, her life was struck by a second tragedy when Hans Knoll was killed in an automobile accident, and she suddenly found herself as Knoll’s sole owner.

Still, Florence Knoll continued to run the Knoll Planning Unit and oversaw all design related aspects of the company, including showroom designs, marketing and advertising.

In 1957, the Knoll Planning Unit began work with the First National Bank of Miami. She married the bank’s head, Harry Hood Bassett, the following year.

Florence Knoll Bassett continued in her capacity as Knoll's president and later as its director of design, but eventually sold the company to Art Metal Construction Company in 1959. Even after her departure from Knoll, the company continued to be inspired by her synthetic view of design and rigorous standards.

1965: After Knoll

Although she retired in 1965, Florence Knoll Bassett periodically rekindled her relationship with Knoll, completing one last planning project and working on exhibitions related to the legacy of the company and her own work in furniture and interiors.

Florence Knoll Bassett's final work in corporate interiors was done for the client Frank Stanton, President of Columbia Broadcasting Services. The design of the CBS Building was completed by Eero Saarinen just before his death, and Florence Knoll stepped in to see the project through to its completion.

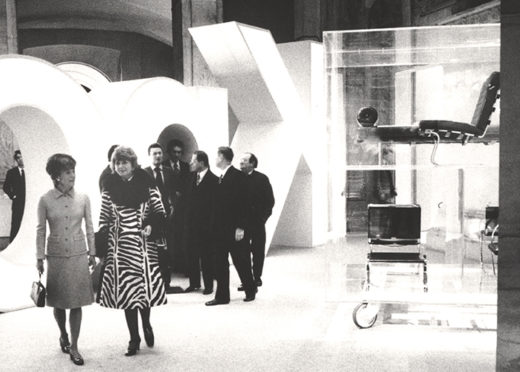

In 1975, she attended the opening of the seminal "Knoll au Louvre" in Paris and, more recently, conceived the design of "Florence Knoll: Defining Modern" at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2004. For the latter show, Shu used her time-tested paste-up method to determine the precise arrangement of objects in a small space at the museum.

The discipline of her practice and the inspired arrow of her ideas were lifelong attributes. In 2002, Florence Knoll Bassett was awarded the National Medal of the Arts, the highest honor for achievement in the field presented annually by the President of the United States.

2017: Reviving the Archive

To celebrate a century of Florence Knoll and her inspired brand of modernism, Knoll expanded the Florence Knoll Collection in 2017 with the addition of new and archival products.

Revived from the Knoll product archive 70 years after its initial introduction, Florence Knoll’s Model 75 Stool is now available as the Hairpin™ Stacking Table. The early design was based on Shu's wire studies done while she was a student at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, which were eventually translated to the immensely popular design for Knoll.

In celebration of the lasting appeal and structured simplicity of the Florence Knoll End and Side Tables, a series of Florence Knoll Dining Tables as well as a Florence Knoll Mini Desk have also been introduced to mark the designer's 100th year.

Similarly, the iconic Florence Knoll Lounge Collection has been expanded to include the Florence Knoll Relaxed Sofa, Settee, and Lounge Chair, which present softer, deeper spins on Shu's original designs.

In the lasting acclaim of the planning projects she spearheaded and the pieces of furniture she quietly designed, Florence Knoll has continually proven her own mantra—that "good design is good business."

By constantly aspiring to Shu's exceptional standards and uncompromising taste, Knoll celebrates the legendary designer's 100th year.