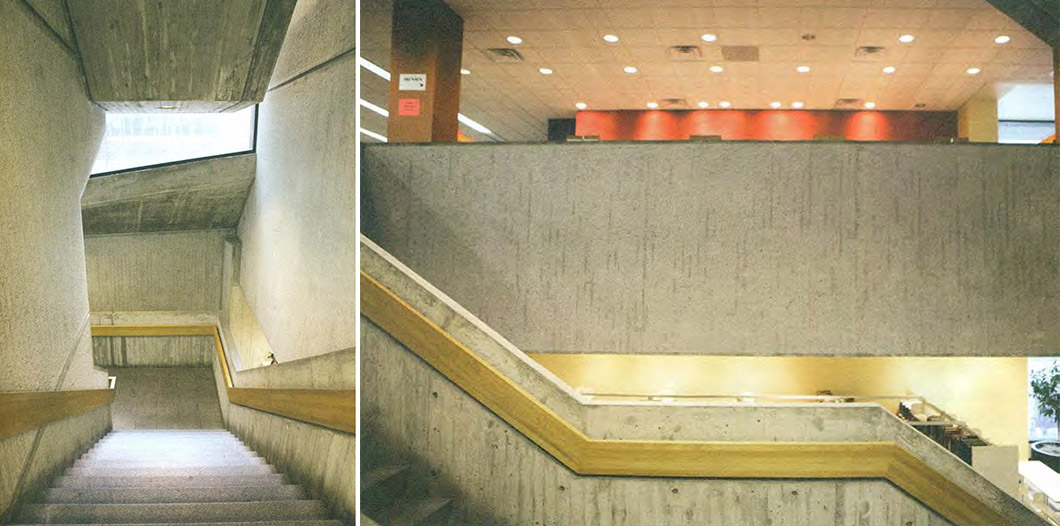

Opened in 1980, the Atlanta-Fulton Central Library was Hungarian architect Marcel Breuer’s final architectural project, regarded by many as a close cousin of his famous design for the former Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. An imposing concrete megalith, the library was meant to appear in stark contrast to its surroundings, to interrupt the transience of urban life with the possibility of a more durable cultural refuge. But while Breuer’s last building appears unwavering in elevation, its supposed permanence in the heart of Downtown Atlanta has recently come into question.

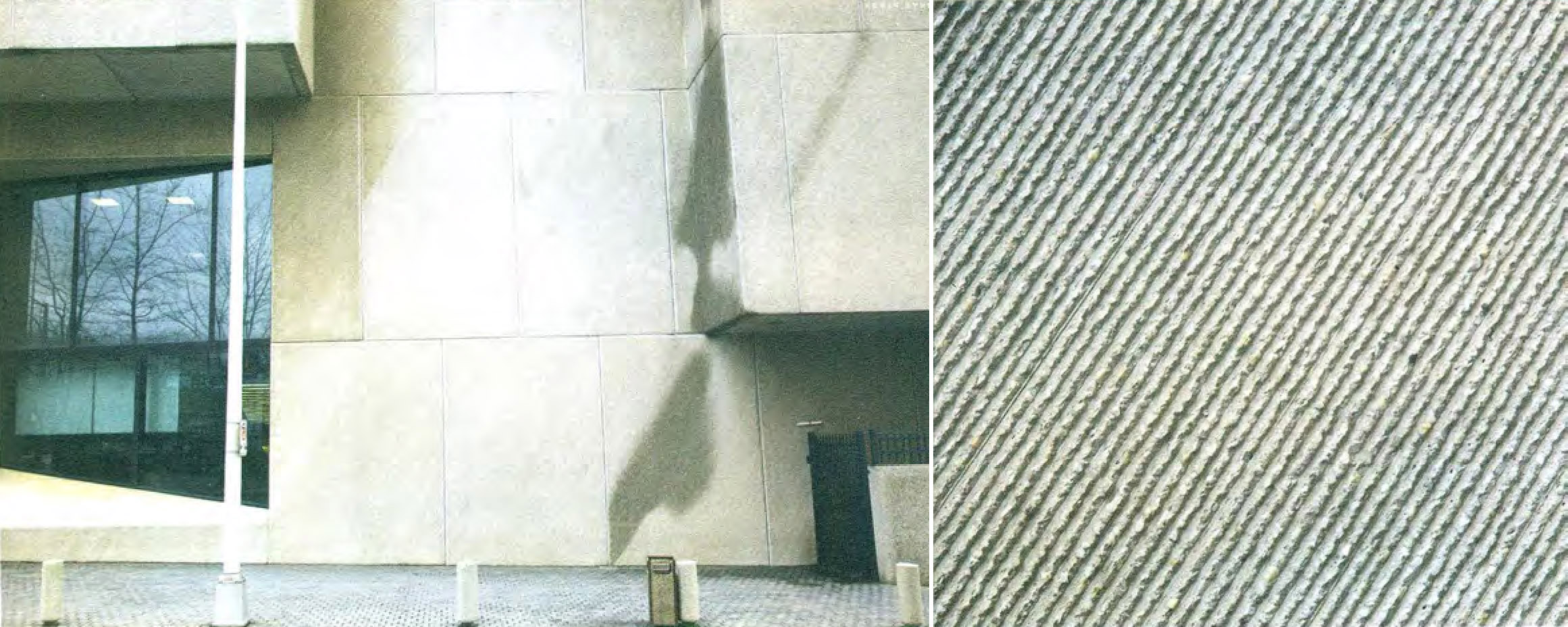

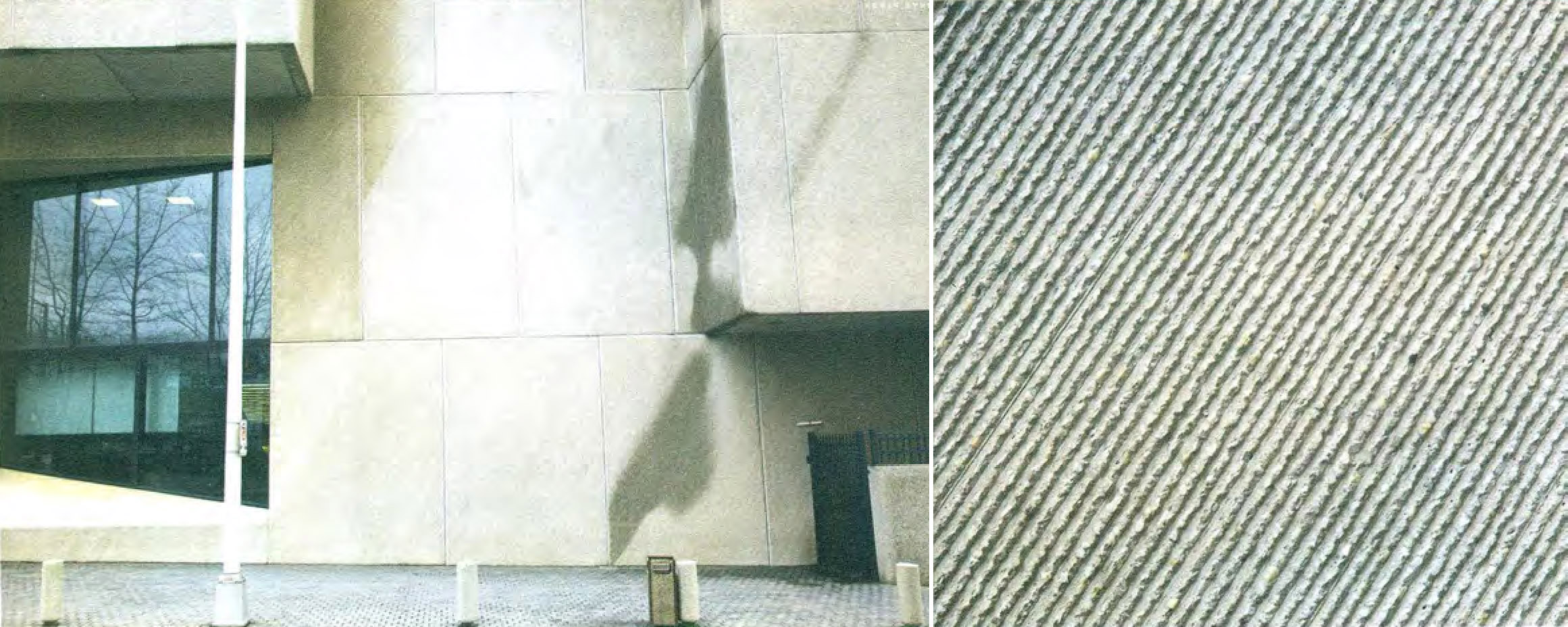

The Atlanta-Fulton Central Library, designed by Marcel Breuer, 1980. Photograph by Kevin Byrd.

In the July/August 2016 issue of Atlanta-based publication Art Papers, Samantha Gregg outlines the ongoing saga of the Central Library, which had been slated for demolition earlier this year. Although public outcry eventually prevented the Atlanta City Council and the Fulton County Board of Commissioners from going forward with the plan, the fate of the institution still remains uncertain. Situating the project as a clear distillation of Breuer’s pared-down design philosophy and formal tendency towards the Brutalist movement, Gregg makes an urgent argument for its preservation.

“Breuer’s designs for such facilities focused on the unique mental and physical separation from daily life that is the domain of any cultural institution,” she writes. “Such buildings were, in other words, designed to serve as meditative spaces of contemplation and respite, away from the haste and the aesthetic of urban life.”

“Breuer’s early achievements in furniture design preface the humanist, socioeconomic sensibilities of his architectural work.”

—Samantha Gregg

The Atlanta-Fulton Central Library, designed by Marcel Breuer, 1980. Photograph by Kevin Byrd.

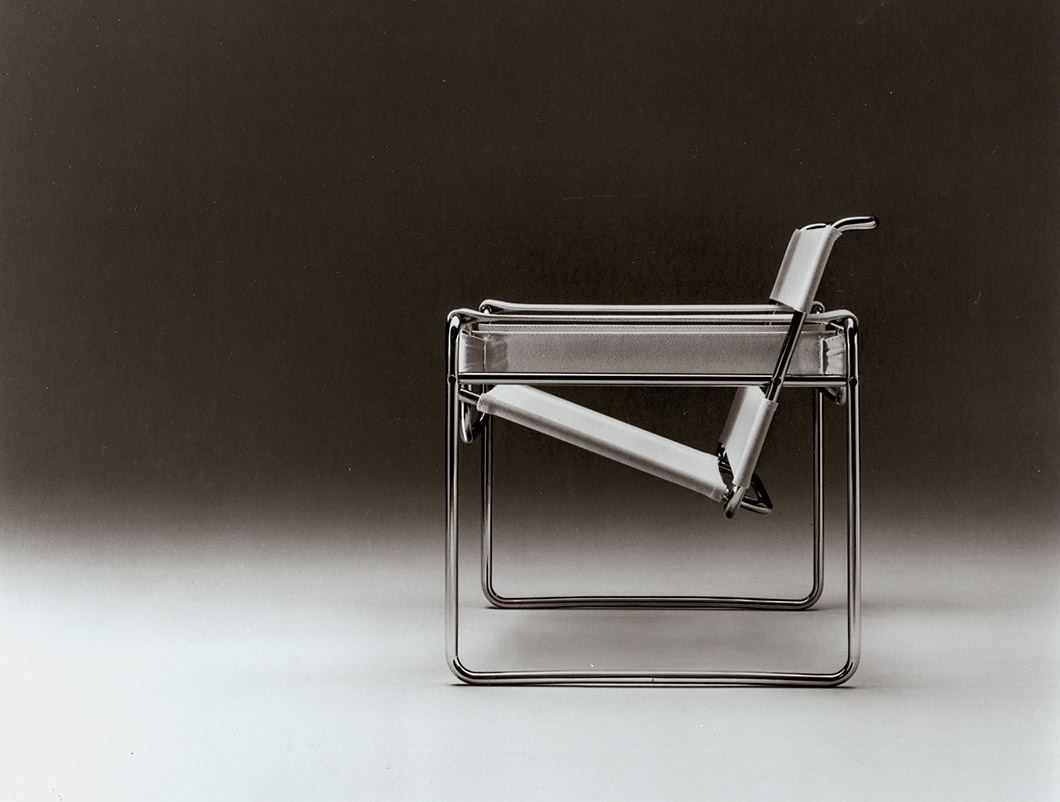

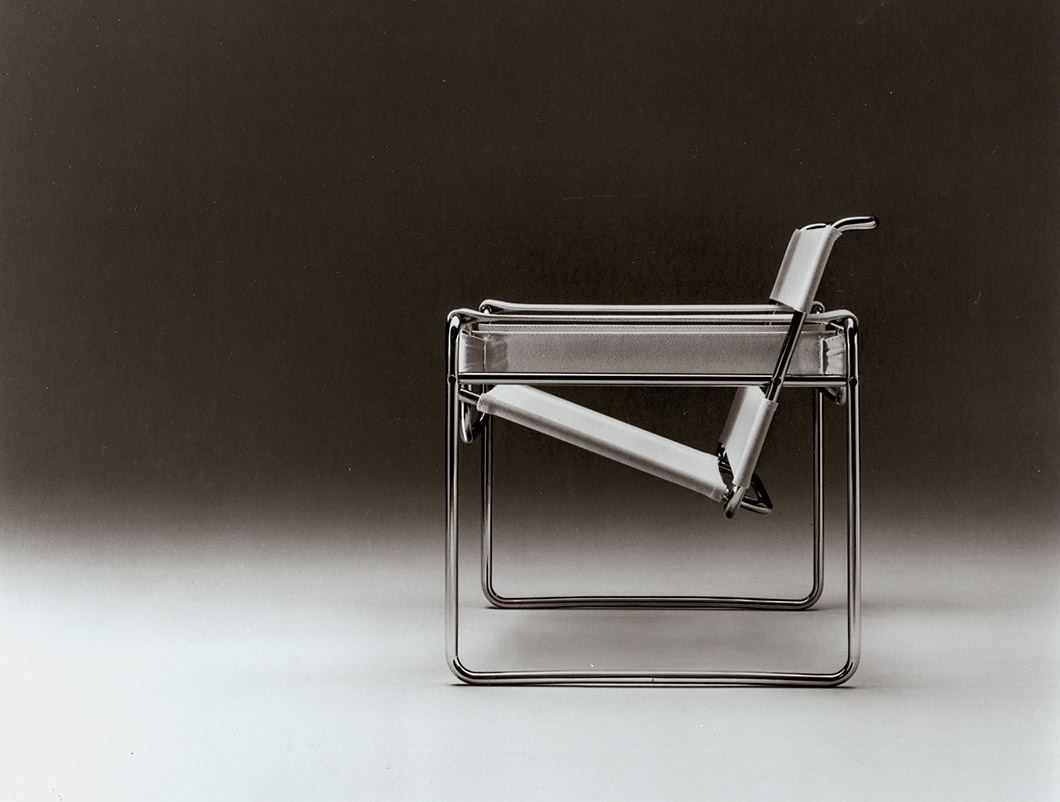

Although operating on a vastly different scale, Breuer’s output as a furniture designer shares the contemplative approach to design found in his architecture. “Breuer’s early achievements in furniture design preface the humanist, socioeconomic sensibilities of his architectural work,” Gregg remarks. “The Wassily, for example, was fabricated using traditional plumbing techniques alongside new industrial materials that were available in large quantity—such as canvas, and bent steel tubing similar to that used in bicycle construction. Combining art and industry, this club chair offered novel elegance to a provident mass market.”

The Wassily Chair, designed by Marcel Breuer, c.1926. Image from the Knoll Archives.

“Architects… should be more connected with the structure of the time, and should work in architecture and furniture for general use.”

—Marcel Breuer

In an interview with Knoll historians around the time of the library’s construction, Breuer contended that designers “should be more connected with the structure of the time, and should work in architecture and furniture for general use.” The humble origins of the Wassily Chair and the civic objectives of the Central Library, which was outfitted with a wide variety of public facilities, attest to this desire. Both works reflect the Bauhaus designer's belief in the inimitable essence of an object, be it a library or a coffee table, and the need to design such objects with honesty. Truthful designs, he argued, would improve one’s overall quality of life—a good building, Breuer once said, “has a human quality. It wants to help you.”

Marcel Breuer at his residence. Photograph by Jon Naar. Image from the Knoll Archives.

“[A good building] has a human quality. It wants to help you.”

—Marcel Breuer

In 2014, Knoll and the World Monuments Fund provided a research grant to help preserve another library designed by the Hungarian architect. Breuer’s Grosse Pointe Library in Michigan was completed in 1953 and houses in situ works by Herbert Matter, Alexander Calder, and Wassily Kandinsky. After fifty years of sustained public use, the building similarly faced the threat of demolition in 2005 and was placed on the 2008 World Monuments Watch. But with the grant, part of WMF and Knoll’s joint Modernism at Risk program, the library was able to document its historic structure and use the research findings in an ongoing conservation and expansion effort.

The Atlanta-Fulton Central Library was likewise placed on the Watch in 2010 and activists hope that after years of disuse stemming from dried-up public funds, growing awareness will give the building a chance to survive.

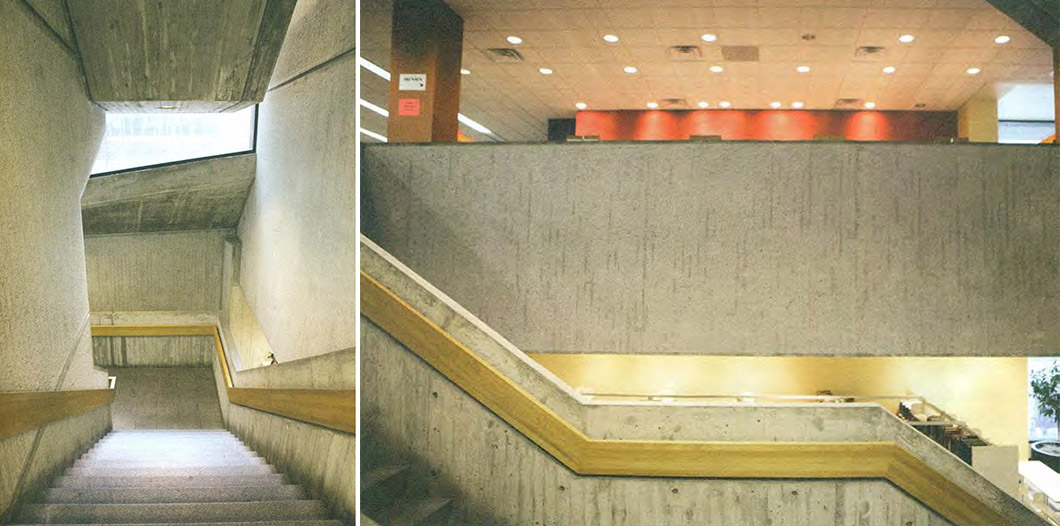

The Atlanta-Fulton Central Library, designed by Marcel Breuer, 1980. Photograph by Kevin Byrd.

“At present, it appears that the Central Library will, albeit slowly, receive its due renovation,” Gregg told Knoll Inspiration. But beyond physical conservation, its survival depends on sustained use by the local community. “Those living in or visiting Atlanta in the coming years possess the ability to exercise individual preservation efforts,” she said. “This can range from the traditional act of ordering of a book to the mere gesture of entering the building, walking the converging concrete paths of the main staircase, gazing up and through one of the circular skylights, and then continuing on with daily life.”

While the upgrade of its facilities is a welcome change, the present weathered appearance of Breuer’s last civic project is, in fact, not indicative of its neglect, but intrinsic to the architect’s original vision. Its worn surface is an illustration of its “exposure to history, uniquely preparing it to cohabitate neutrally with the effects of time.” Gregg concludes that “almost all new buildings eventually grow old; the ones that do so beautifully are those that have been designed with this process in mind.” It is hoped that the Atlanta-Fulton Central Library will be allowed to age with grace.

“Almost all new buildings eventually grow old; the ones that do so beautifully are those that have been designed with this process in mind.”

—Samantha Gregg