Helen Risom Belluschi is one of Jens Risom’s four children and, along with her sister Peggy, an everyday companion for the soon-to-be centenarian. In spite of his upcoming 100th birthday on May 8, Jens Risom (pronounced ree-sum) has remained as committed as ever to the design program he first embarked on almost eighty years ago. With the help of his son, Sven—who assists his father with his late-career projects—Risom has collaborated with Chris Hardy as recently as 2014 to produce a series of new designs, and has been working with Knoll, DWR and Ralph Pucci on several re-releases and reproductions of designs he completed in the 1940s and 50s. Today, it seems, the answer is (still) Risom.

On occasion of Risom’s 100th birthday, and in anticipation of an outdoor line of Risom’s to come, Helen graciously agreed to speak on her father's behalf about his early years in America, at Knoll and during WWII.

650 Line Lounge Chair by Jens Risom, c. 1942. Image from the Knoll Archive.

“My dad went into furniture because he wanted the control. My father wanted the product to leave the factory as he intended it.”

—Helen Risom

KNOLL INSPIRATION: Jens Risom’s father, Sven Risom, was a successful Danish architect. To what extent did his father’s vocation inspire Risom's own?

Helen Risom: Yes, he was reasonably successful. He wrote a book on stamped earth houses, he did some popular buildings and some government buildings. But my dad went into furniture because he wanted the control. An architect does something and then the contractor changes it, et cetera. My father wanted the product to leave the factory as he intended it. You could put your own fabric on it after the fact, but not before, when it was under his name.

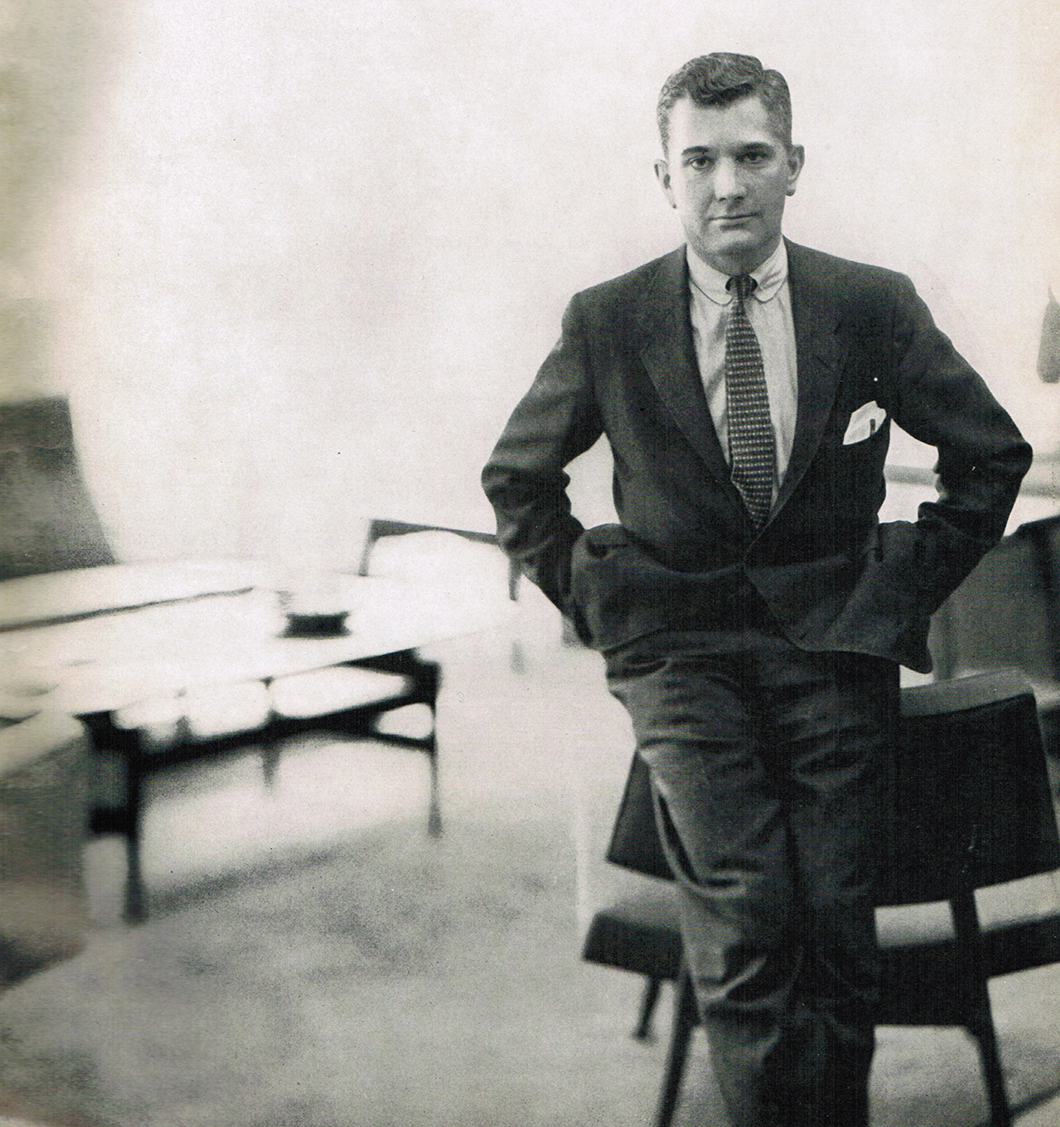

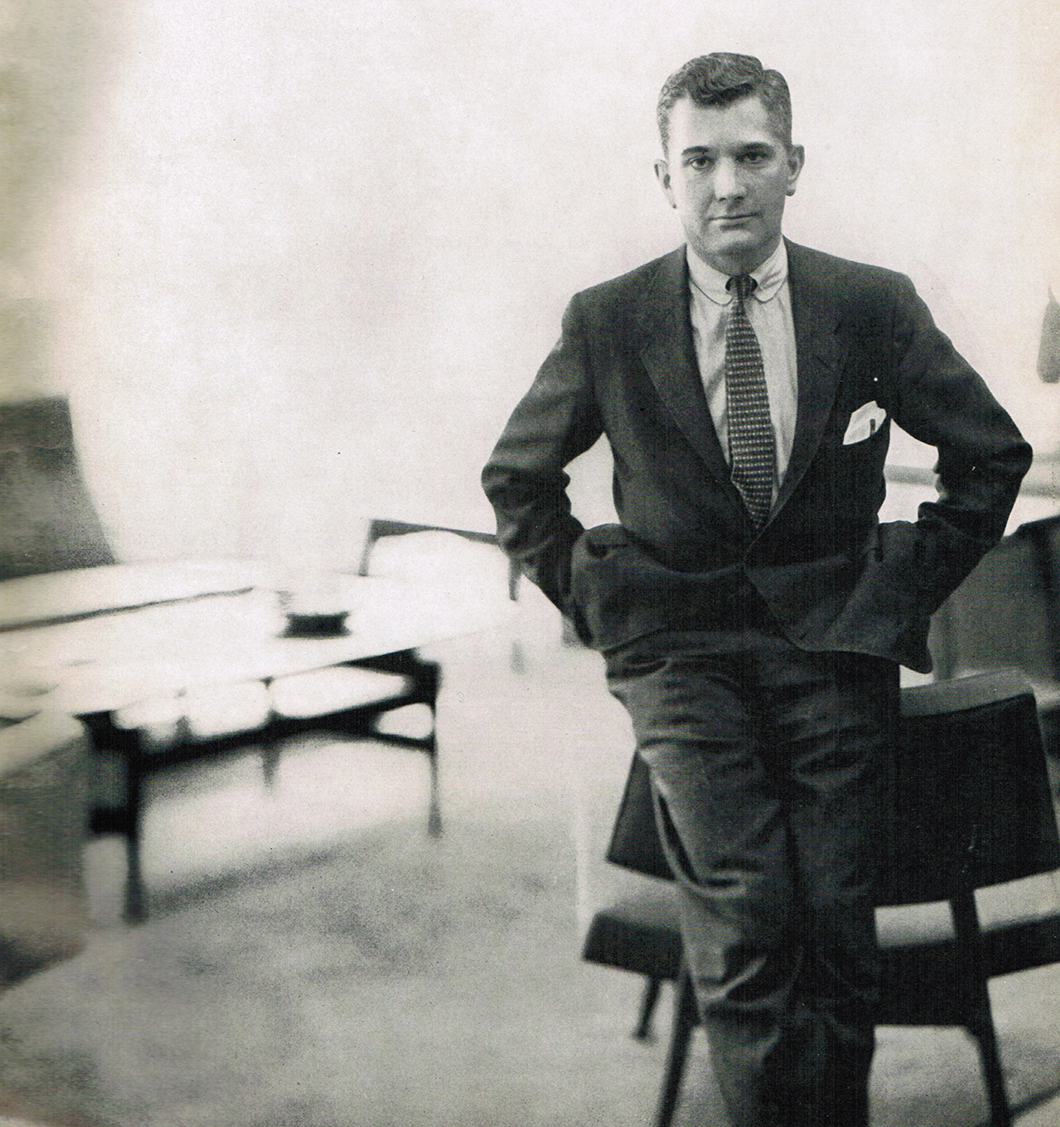

A young Jens Risom, c. 1939. Image courtesy of Jens Risom.

Prior to immigrating to the US, Risom studied and worked in Copenhagen at a very particular moment in time. He was classmates with Hans Wegner and Borge Mogensen and, while working in the design department at Nordiska Kompanient, he met Alvar Aalto and Bruno Mathsson. What, if anything, did he learn from these other great Scandinavian modernist designers?

You have to remember that in ’39 he would have been just 22 or 23. So he didn’t have a big, long history in Copenhagen.

While in school, he did all kinds of different projects, like this dressing table, here. But he came over to America because he wanted to see what they had in terms of furniture. He was appalled—there was nothing. Not only that, he couldn’t get a job because there was nothing available in what he was looking for: furniture design. It practically didn't exist.

“People didn’t know what they wanted; they didn’t know there were options. So these demonstration houses were really showcasing a new way of living—the purpose was to get out there and do the talk shows.”

—Helen Risom

Collier’s House of Ideas designed by Edward Durrell Stone, Dan Cooper and Jens Risom, c. 1940.

Photography by Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc. Image courtesy of The Library of Congress.

In the US, Risom’s first commissioned works were for Collier’s House of Ideas, a model house designed by Edward D. Stone and built on the terrace of Rockefeller Center overlooking Fifth Avenue. This was around the same time as the “demonstration houses,” installed in the courtyard of the Museum of Modern Art, and just before the famous Case Study Houses erected in Los Angeles, c. 1945. What questions, problems or solutions did these model houses pose?

The purpose was for people to see these houses, and the furniture within them. People didn’t know what they wanted, they didn’t even know there were options. You just went Ethan Allen to buy a chair—“You mean there’s something else?” It was that kind of mentality. Most people hadn’t been to Europe or they had emigrated away from it. So these demonstration houses, the Edward Durell Stones etc., were really showcasing a new way of living—the purpose was to get out there and do the talk shows. And all of this was pretty damn exciting for a guy who wasn’t even twenty-five.

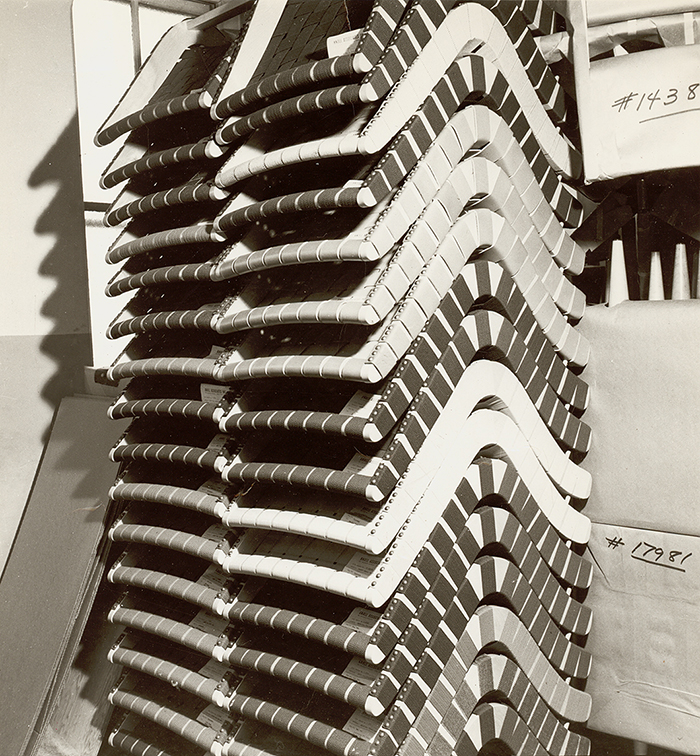

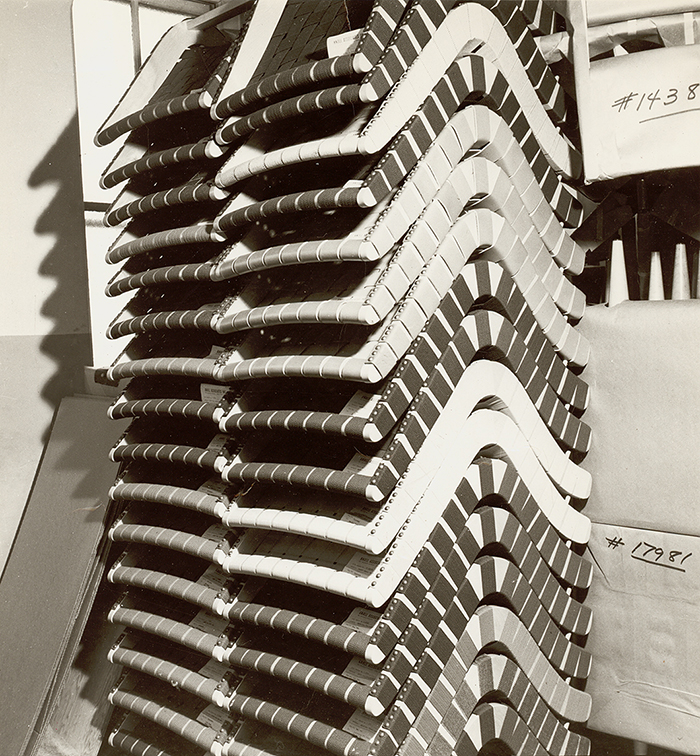

Jens Risom designs for Hans Knoll Furniture, 1942. Image from the Knoll Archive.

In 1940, Risom and Hans Knoll connected at an interesting point in their careers. Hans Knoll was getting Hans Knoll Furniture Company off the ground, and Risom was studying American design while trying to establish his career in America. What was that time like? How would you characterize your father’s relationship with Hans Knoll?

I wouldn’t say that he and Hans were social friends, but they did drive all the way out to California—which was not something people did back then—to find out “where it was.” Ultimately, they decided on New York.

Shu wrote recently that she had been going through some old photo albums and she had come across some photographs of me with George Nakashima and [his daughter] Mira, so I’ve recently reconnected with them. There’s some overlap in their furniture, but they were very different in how they approached projects.

“It wasn’t the wood that was difficult to get, it was the fabric. When he came across the parachute webbing, he thought, ‘I bet we can use that.’ It was a product of that kind of thinking, because there simply wasn’t anything extra in those years.”

—Helen Risom

650 Line Lounge Chairs by Jens Risom, c. 1946. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Several years earlier, Risom created a series of textiles for a job interview with Dan Cooper, the fabric and interior designer at MoMA. Did this foray into textile design prove useful when he found himself restricted to excess parachute webbing and off-cast wood at the outbreak of the war?

I don’t think so. First of all, he ended up with Dan Cooper, who was an independent textiles person. He only designed a few of Dan’s fabric patterns and some other things, but not enough for it to have a meaningful impact on his process.

As for the wartime shortages, there was plenty of surplus, but they couldn’t get basic cottons. So it wasn’t that the wood was so difficult to get, it was the fabric. When he came across this defective, discarded parachute webbing, he thought, “I bet I can use that." It was a product of that kind of thinking, because there simply wasn’t anything extra in those years. The war broke out over there in ’39 and ’40, so everything disappeared fast.

Playboy “Design For Living,” c. 1961. Image courtesy of Jens Risom.

What happened after the war? Jens Risom left Knoll, Inc. shortly thereafter.

During the war, Knoll had moved forward, and when dad returned in November 1945, he decided it was time for him to head out on his own. He started Jens Risom Design on May 1, 1946.

With Shu [at the helm], the two didn’t have reason to collaborate, but they parted amicably. Socially, dad and Shu liked each other, but they didn’t see each other much. None of them did. Like, that whole group in the Playboy picture [from 1961]. They knew of each other, but that was the one day. You would have thought that they might want to get dinner. But no, they had trains to catch. It’s hard to imagine: there you are, sitting on top with the best in the industry, right down the line.

“He can’t forgive a piece furniture that fails his criteria. It drives him crazy.”

—Helen Risom

Jens Risom’s patent for a chair frame, c. 1943. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Risom has never stopped designing. At this point in his career, how does he look back on these early, celebrated designs?

It’s funny because my daughter went to RISD [Rhode Island School of Design], as did I, and all her classmates want to talk to Mr. Risom, especially the ones who want to go into furniture. They want to know, “What do you think of this?” He’ll look at them and ask, “Do you really want to know?” Because he’ll tell them, “This is wrong, that’s not comfortable, that’s going to crack, etc.”

From the early days to now, my father has always had a phenomenal appreciation for natural materials, especially the woods. You'll also notice that there are no screws or nails that you can see in his designs. The whole assembly process is vital to him, how it works. He can’t forgive a piece furniture that fails these criteria. It drives him crazy.

I’ve got a huge stack of drawings that went nowhere. He would sit at his desk and create furniture for imaginary clients by the rolls. He could just crank out that yellow trace [paper].

Jens Risom’s early designs for Knoll, c. 1940s. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Risom has said that contemporary design is created “in our time for today’s people, environments, habits and activities.” While created for a different time, I think it’s safe to say that his designs still respond to today’s people, habits and activities. What does Risom make of his designs’ cross-generational appeal?

He was surprised when it all started coming back, but "modern" is not a word his generation used. It was “contemporary”—to the moment, to the people, to the living environment. To this day, his designs fit that objective. Even when paired with antiques, they fit in fine. Good design will work with good design, forever.

“Good design will work with good design, forever.”

—Helen Risom

Jens Risom's 650 Line Lounge Chair with arms. Photography by Ilan Rubin.

Discover The Risom Collection

All images are from the Knoll Archive or courtesy of Jens Risom unless otherwise noted.