With its commitment to quality and cutting-edge design, Knoll has found its way into countless museums over the years. Whether temporarily on display in exhibitions or included in the permanent collections of leading art institutions, Knoll furniture has become synonymous with the vanguard of twentieth-century modern design. But perhaps no other installation has come close to the ambition, scale, and acclaim of the 1972 Knoll au Louvre exhibition in Paris.

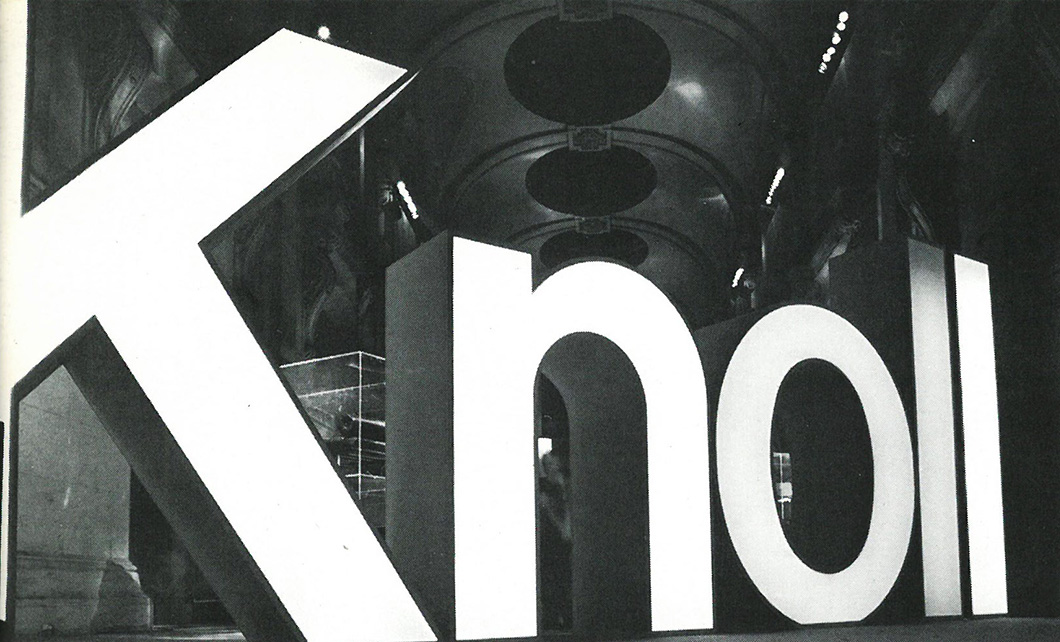

Knoll at the Musée du Louvre. Image from the Knoll Archive.

We were like a very close family and had a lot of spirit and everybody was working very hard.”

—Yves Vidal

Years in the making, Knoll au Louvre was a collaborative effort across continents, organized on-the-ground by Yves Vidal, President of Knoll Europe, in Paris, but conceived by Massimo and Lella Vignelli and Knoll associates in New York. In an interview years later, Vidal recalled the passion that had made the project such a success. “That’s the main thing, the spirit,” he said. “We were like a very close family and had a lot of spirit and everybody was working very hard.”

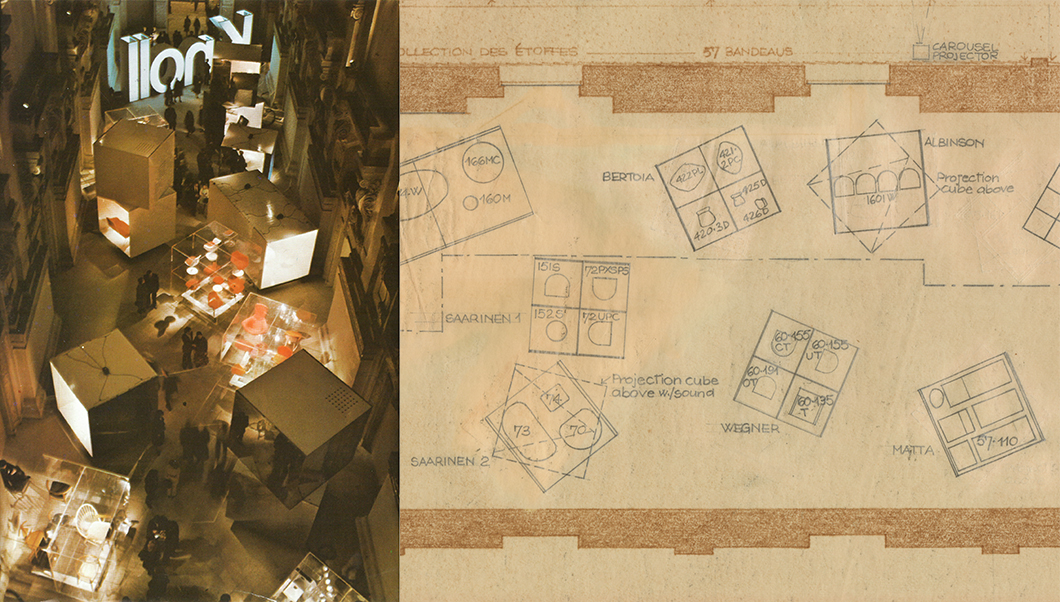

Hard work and a fair amount of ingenuity was needed to pull it off, for the show was to take place in a space whose size and grandeur was intimidating, to say the least. Sited in the Pavillon Marson, built by Napoleon III during France’s Second Empire and now part of the Museum of Decorative Arts at the Louvre, the exhibition space was a looming chamber of limestone piers and arches. Immediately, it prompted a dilemma in scale—the question of how to exhibit pieces of modern furniture in a space the size of a football field, with ceilings impossibly high.

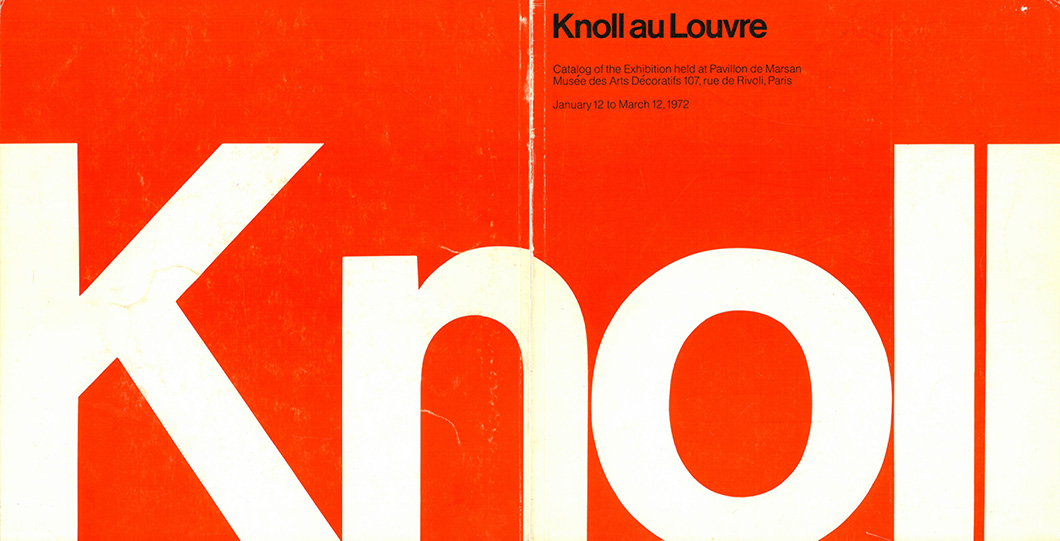

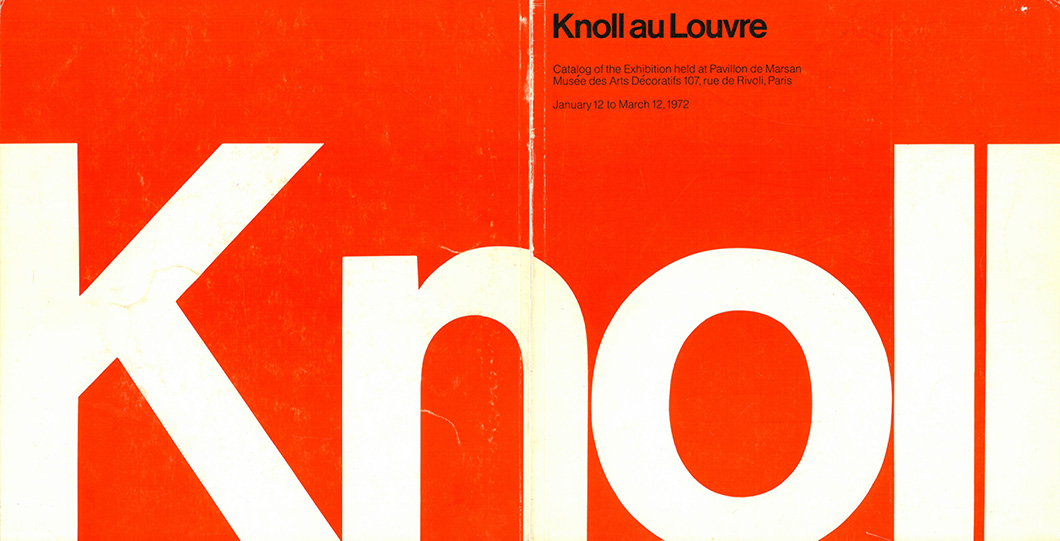

The Knoll Au Louvre exhibition catalog, designed by Massimo Vignelli. Image from the Knoll Archive.

But for Massimo and Lella Vignelli, graphic designers whose aesthetic dexterity had already refreshed the Knoll brand identity, the answer was born out of happenstance. “The specifics of the problem of designing the exhibition Knoll Au Louvre were how to show 3-foot-high objects in a 45-foot-high space,” recalled Massimo Vignelli. “We needed a catalyzing element to restore the reference from the object to its use.”

“Lella and I were searching for that catalyzer when I happened to turn my hand to a shelf behind me—there was a bunch of small plastic cubes there. All of a sudden it was very clear: I took the cubes, rolled them over the plans spread out before us, as if they were dice. Lella said, ‘that’s it.’ So we reconstructed the same action in our presentation to Knoll, got their approval, and started to work on this fascinating exhibition.”

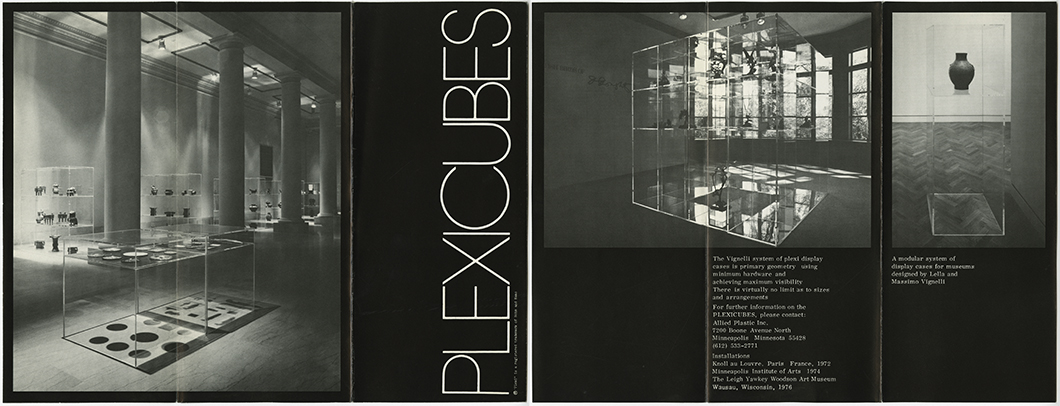

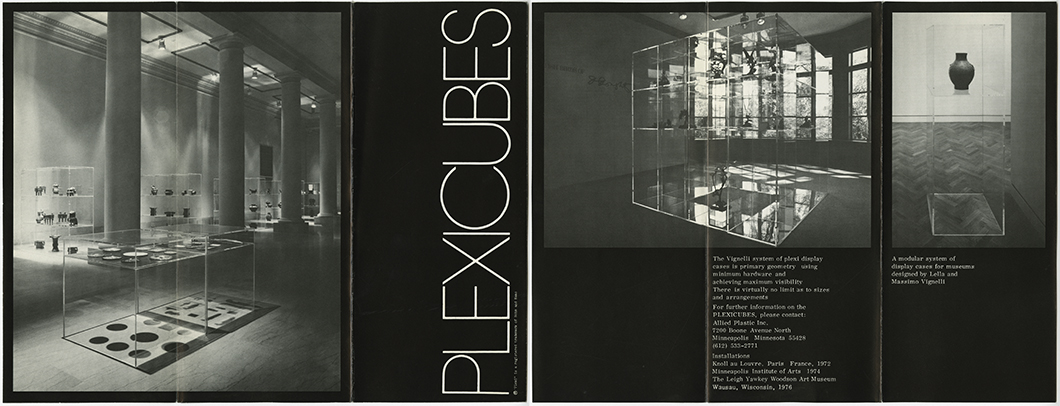

A brochure for the Vignelli Plexicube display system. Image courtesy of the Vignelli Center for Design Studies.

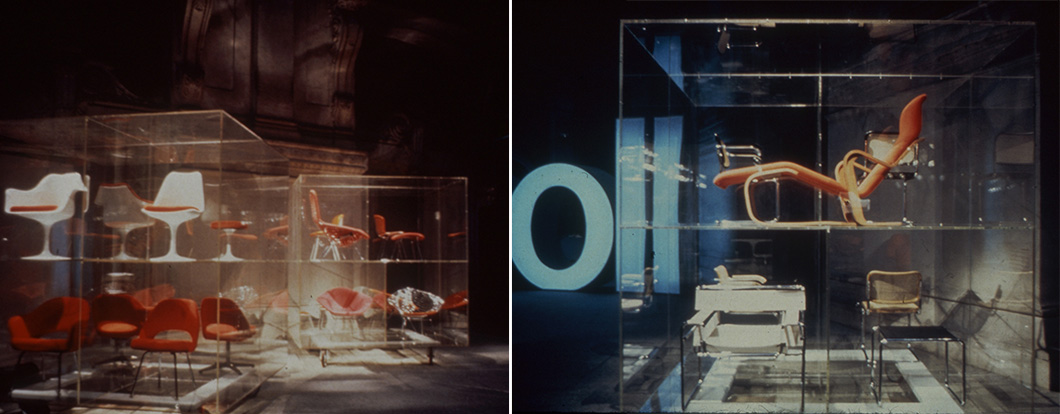

Echoing the same rigor of the gridded brochures and price lists they had designed for Knoll, the Vignellis developed a modular display system they called Plexicubes, described as “primarily geometry, using minimum hardware and achieving maximum visibility.”

With the aid of the Rossi Brothers, a Milanese display house, an army of eight-foot-tall cubes of plastic and polished steel, all mounted on industrial casters, were fabricated for the exhibition. “I was familiar with [the Rossi Brothers’] dedication to craftsmanship and design, and we really needed that in Paris,” said Massimo Vignelli.

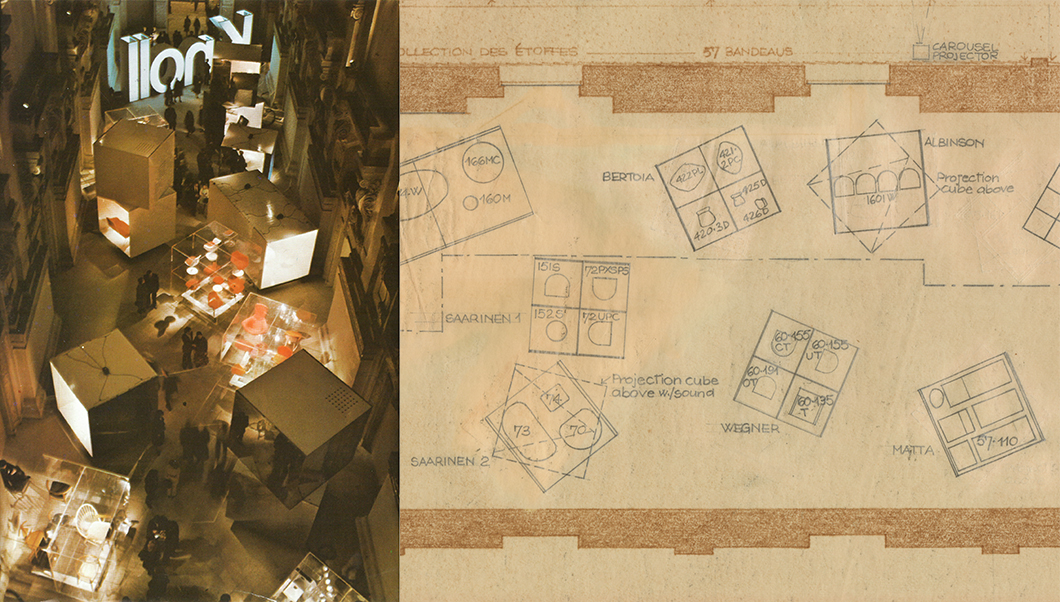

Left: Display cubes for Knoll Au Louvre in the Pavillon Marson. Image from the Knoll Archive. Right: Exhibition plans for the arrangement of the display cubes. Image courtesy of the Vignelli Center for Design Studies.

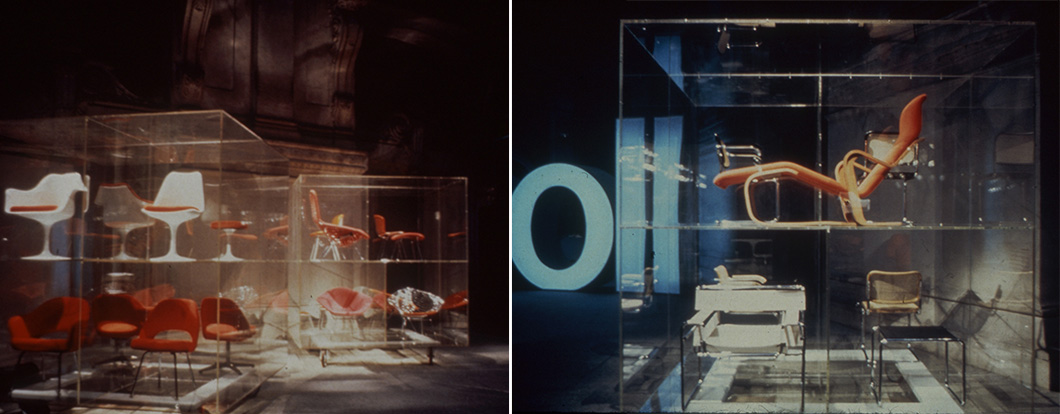

With Knoll designs housed in glass boxes that were strewn across the room, the furniture no longer seemed dwarfed by the massive dimensions of the Pavillon Marson. A second section of Knoll Au Louvre played with geometry even further, in a continuation of the immersive exhibition experience.

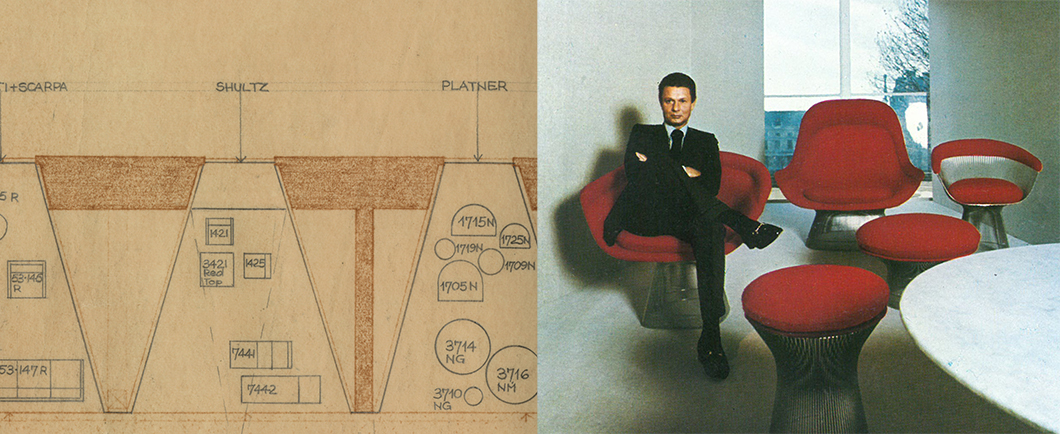

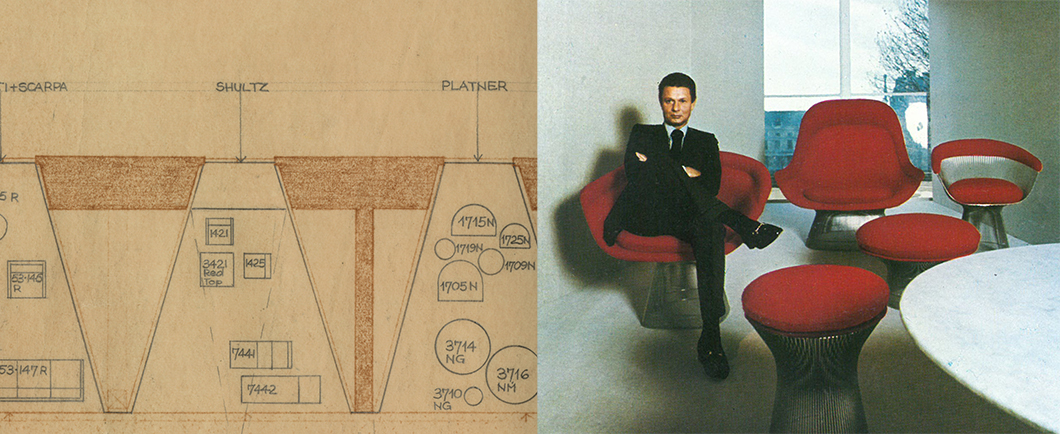

Left: Exhibition plans for the linen-walled spaces. Image courtesy of the Vignelli Center for Design Studies. Right: Yves Vidal in the display area for the Platner Collection. Image from the Knoll Archive.

“In the section toward the park we zoomed into the windows to create a wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling unified space so that the window became a glass wall, so to speak—the end of a false perspective entirely covered in natural linen,” explained Vignelli. At the end of the false perspective, windows framed cropped views of the famed Tuileries Garden, once again accentuating the contrast between tradition and the avant-garde.

“We zoomed into the windows to create a wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling unified space so that the window became a glass wall, so to speak—the end of a false perspective entirely covered in natural linen.”

—Massimo Vignelli

The entrance to Knoll Au Louvre, flanked by French cavalry. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Archive of American Art.

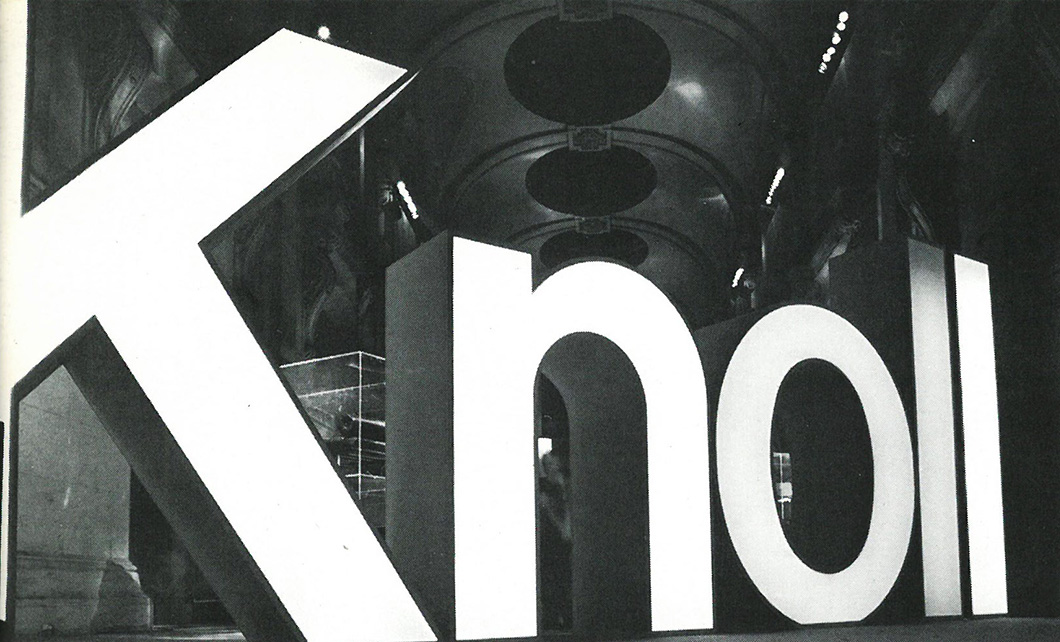

Indeed, from the entrance to the exhibition itself, Knoll Au Louvre hinged on the theatrical combination of new and old. Exhibition-goers first ascended a staircase “flanked by cuirassiers wearing plumed helmets and shiny breast-plates” and were then greeted by a row of huge white letters that spelled out the company’s name.

Walking through an arch formed by the ‘n’ of Knoll, visitors were faced with the full expanse of the Pavillon Marson, free to walk between the scattered cubes and view the sleek forms of Knoll furniture against the backdrop of the richly ornamented room. According to one visitor, spotlights mounted in the upper balustrades sent down beams of light “that seem to pierce not only the dust-laden air but years and years of time.”

Massive, metallic letters spelling out Knoll at the entrance to the exhibition. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Inside the cubes and the inhabitable spaces constructed out of linen, furniture was grouped by designer and upholstered in Knoll red, giving the sprawling exhibition a sense of visual unity. Along one side of the gallery hung a fifty-foot-high display of fabrics from KnollTextiles, while a visual presentation of the Knoll timeline—with accompanying “sound environments”—was projected on linen screens above the cubes. It all added up to a dynamic, expressly modern affair.

Furniture by Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia and Marcel Breuer displayed in transparent cubes, upholstered in Knoll red. Images from the Knoll Archive.

“The show at the Louvre was fantastic,” recalled Vidal. “It was a very beautiful opening. There were French Ministers and Mrs. Knoll came specially to open it. I think she was extremely moved; so was I.”

And the acclaim was unanimous. “The reaction was very good from the public,” said Vidal. “The press was fabulous. They did an incredible number of articles and photographs, both in Europe and in the States. I think it was kind of a consecration of Knoll as the number one in the field.”

“[Knoll Au Louvre] was lavished with attention from a press not normally given to praise for an American company, a German tradition, and the visible presence of Italian style.”

—Eric Larrabee

Knoll furniture on display in the Pavillon Marson. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Although still a young company in 1972, Knoll had already entered the annals of leading art institutions, and many saw the Louvre exhibition as the decisive confirmation of its cultural status. Writing in Knoll Design, historian Eric Larrabbee noted that it was “lavished with attention from a press not normally given to praise for an American company, a German tradition, and the visible presence of Italian style.”

Le Monde called it “the artistic legitimization of commercial fame” while Olga Gueft, editor of Interiors, commented that Knoll had finally been “formally accorded official recognition as one of the epoch-making forces in the history of design.”

Florence Knoll with a group of French diplomats and government ministers at the Musée du Louvre. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Archive of American Art.

But perhaps the ultimate word of approval came from the company’s most passionate critic—Florence Knoll herself. Arriving with a contingent of French government ministers and diplomats, the retired designer brought “a glow of celebrity” to the exhibition opening, surrounded by many of her own furniture designs as well as all those she had helped to perfect. “The conception of using plastic cubes to house the furniture in the huge space was indeed brilliant and was a great success,” she later wrote, recalling the exhibition in her personal archive.

Although only on view for a few months, Knoll Au Louvre was instrumental in cementing the company's prestige and place in the eyes of the European public. With its bold format and unapologetic originality, the exhibition proved that modern design was not antithetical to the storied heritage that formed the continent's cultural backbone. Instead—and as the afterglow of Knoll au Louvre proved—the unlikely combination could often produce spectacular results.

All images from the Knoll Archive unless otherwise noted.