1945-2017

Today, Knoll remembers Jeffrey Osborne, an influential voice in the furniture and design industry, who passed away on March 24 at age 72. Osborne was with Knoll for twenty years, holding the positions of Director of Marketing and Director of Products before becoming Vice President of Design in 1976.

Known for his informed opinions, generous disposition and extensive bowtie collection, Osborne steered the company during the ‘70s and ‘80s to a position that reconciled its Bauhaus roots with a supple, optimistic future. Having grown up in Michigan with an awareness of the designers coming out of the Cranbrook Academy of Art and written college papers about Knoll, Osborne joined the New York office with a longstanding appreciation of the furniture company. He worked under Director of Marketing Jim Mauri as manager of marketing services, advertising, graphics, public relations and product introductions, before moving on to work to develop new products with several talented architects and designers.

Recalling his time at Knoll in an interview for Eric Larrabee and Massimo Vignelli’s Knoll Design, Osborne noted his tendency to probe the philosophical underpinnings of the company’s design decisions in a way no one else was doing at the time. “When I came to New York, I was just out of a masters program in marketing,” he said, “and I was saying—why are we doing this product? What’s the intention of it?”

Around the time of the 1972 Knoll Au Louvre exhibition in Paris, Osborne saw an opportunity to define the mission of the company, writing a 25-page report that outlined Knoll's current status in the industry and recommending a more holistic approach to product planning. When he presented it to the company's new owners in 1977, Osborne added the epigraph: “Design never exists in a vacuum. Art might. Taste is neither of the above.”

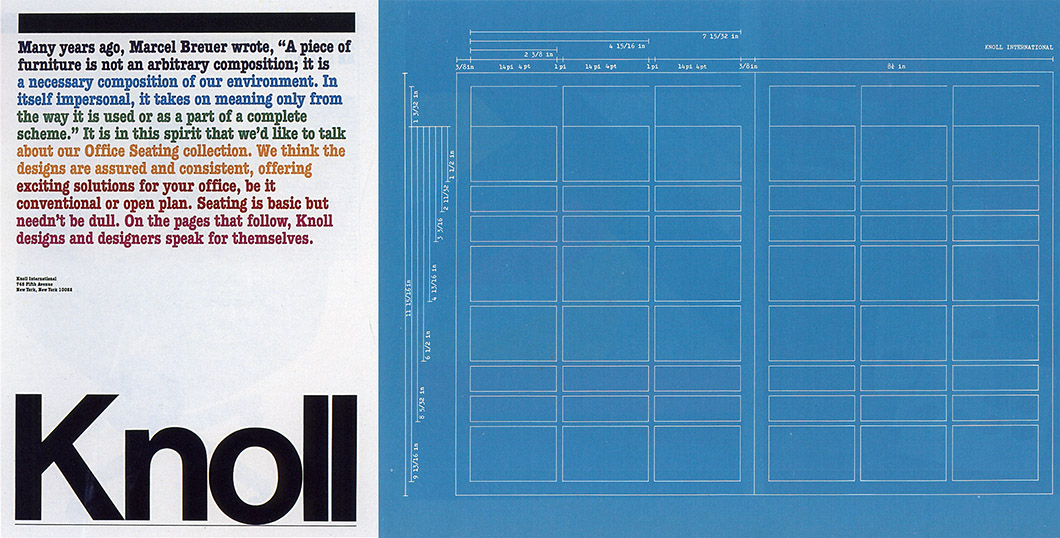

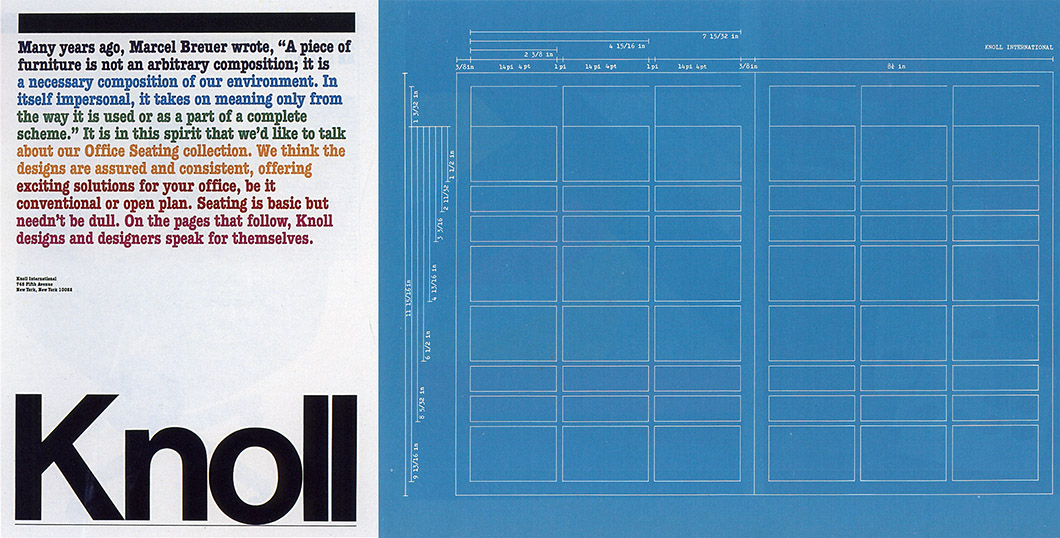

Massimo Vignelli's broadsheet brochures and price list grid, designed for Knoll with the guidance of Osborne. Images from the Knoll Archive.

Eager to develop a more thorough framework of design development that would guide the company through an uncertain period in its history, Osborne acted as the keeper of Knoll’s founding philosophy and commitment to timeless design, translating its ethos to fit its present predicament. Early on, he worked with Christine Rae and Massimo Vignelli to develop a fresh marketing strategy for Knoll, a project that ended in Vignelli’s infamous “tabloids”—brochures printed on newsprint in response to the traditional glossies that pervaded the furniture industry.

"The way the tabloid happened—and I don’t take that much credit—is I put together a complete spectrum of everything going on in graphics and everything anyone else had ever done," Osborne recalled, "and we worked with Massimo to really rethink another approach to do this. It was during this period I got to know Massimo and enjoyed the relationship. Christine, Massimo and I really got a lot done and had a good time doing it."

Richard Meier's unmistakably modernist furniture collection. Image from the Knoll Archive.

“In design leadership, it’s design of thought as well as the object that fulfills it.”

—Jeff Osborne

In his role as Vice President of Design, Osborne stressed the importance of developing a stimulating, generative working environment, bringing together practitioners across craft and industry to achieve the highest standard in furniture and systems design. He worked with architects and designers representing a spectrum of styles, from Richard Meier to Ettore Sottsass, Cini Boeri to Otto Zapf.

“It seems that there’s few businesses where one is consciously developing products with a sincere desire that they will last a long time and will not go out of style,” he said. “One would think of a furniture company being involved in style, yet your greatest success would be to come up with something that doesn’t go out of style.”

“In design leadership, it’s design of thought as well as the object that fulfills it. You have the responsibility of allowing spontaneity and a certain amount of fun in the ideas so you can transcend other companies’ products. You have to create an atmosphere, a relationship of people, some of the best minds to play off of each other.”

Robert Venturi's polemical collection of furniture, designed in the 1980s. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Osborne worked on a range of products during his tenure, believing in Knoll’s responsibility to stay immersed in contemporary architectural debates through its product offerings. As Postmodernism became the most polemical architectural style of the twentieth-century, Osborne brought on Robert Venturi to design a collection of furniture made of molded plywood.

Reflecting on the collection, Osborne recalled: “I think it’s important that Knoll shake-up the community that looks at us as the classic company upholding the Bauhaus thinking—that was fifty years ago. Venturi and his firm have pioneered some fresh thinking and are at least a reference point to a whole new direction in architecture.”

“[It] is a continuation of what Knoll is known for—the slick quality, refined detail, hidden connections, a little bit of mystery. You’re not sure how it all went together and stayed there.”

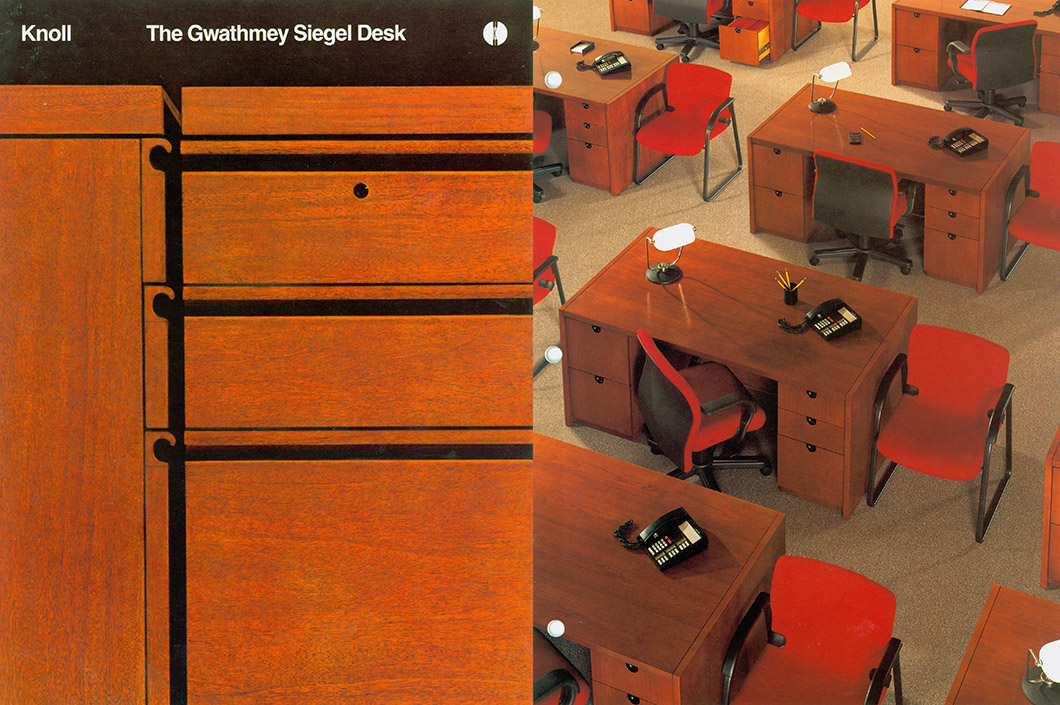

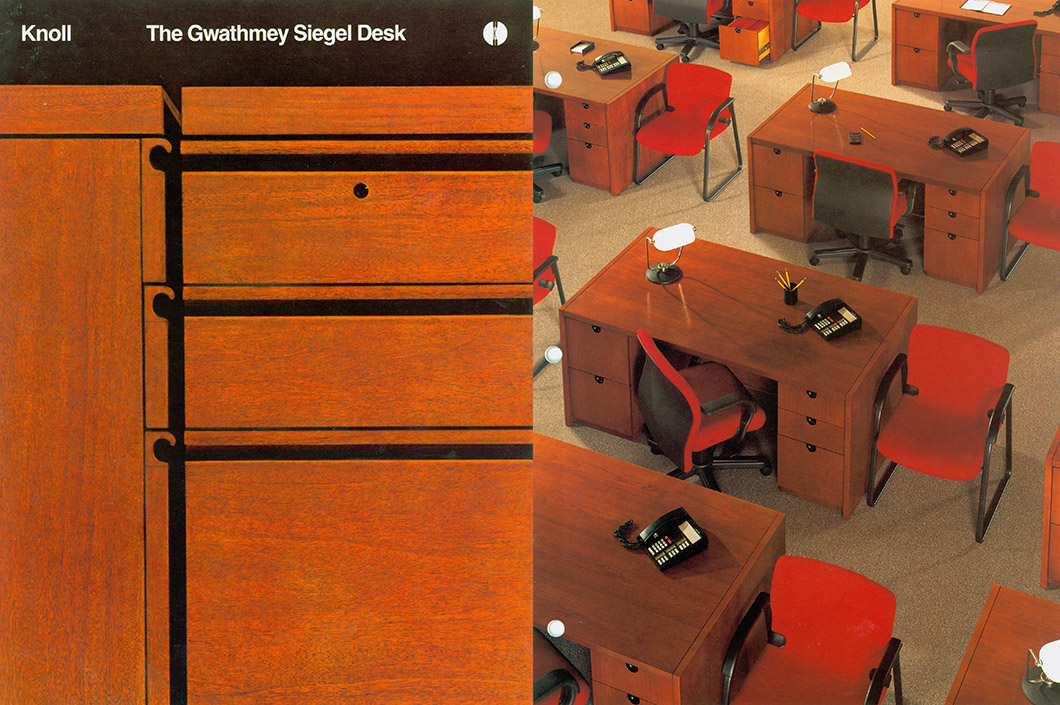

Office furniture and system designs by architects Charles Gwathmey and Robert Siegel. Images from the Knoll Archive.

Throughout his time at Knoll, Osborne got to know the company deeply, and was never afraid of asking the tougher existential questions. “Knoll, from the beginning, was always an idea,” he stated in his interview. “That kept it going. What it wasn’t for a long time was a business. How do you continue to grow and come up with business-corporate understandings of growth, while at the same time provide an umbrella and nurture the same freshness of thinking that Hans and Shu allowed? It’s difficult. I think that’s really the challenge of Knoll.”

He took that challenge on personally. “How do you resurrect a spirit within a company?” he asked. “I think it has to do with pursuance of excellence. How do you define excellence? How do you put together a business background and design background so they work?”

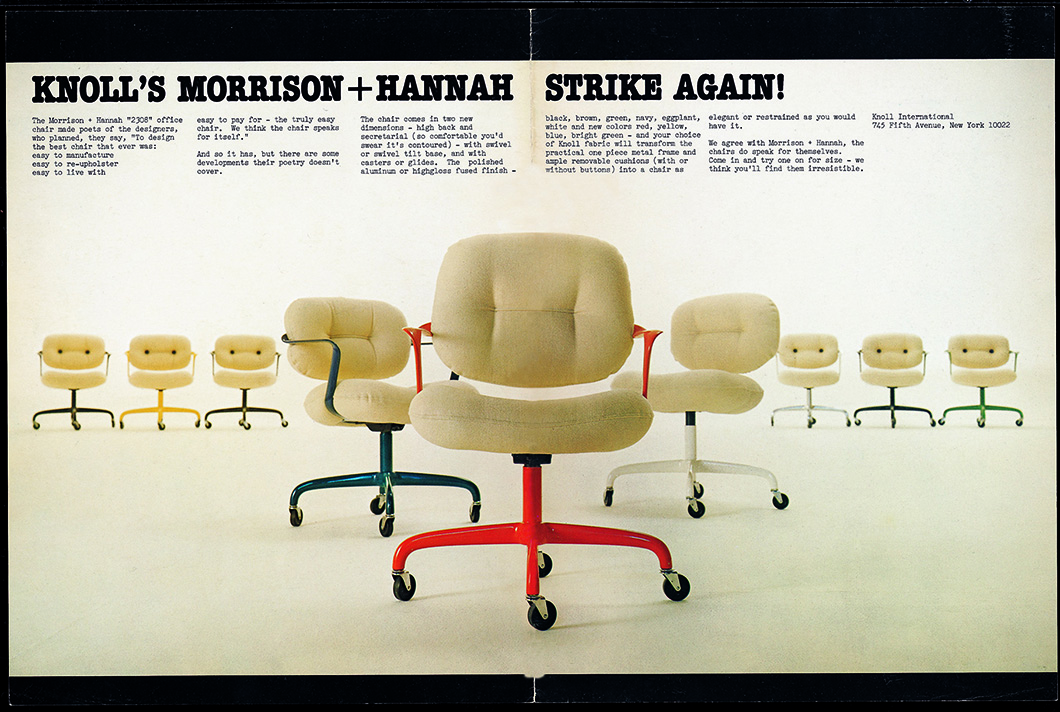

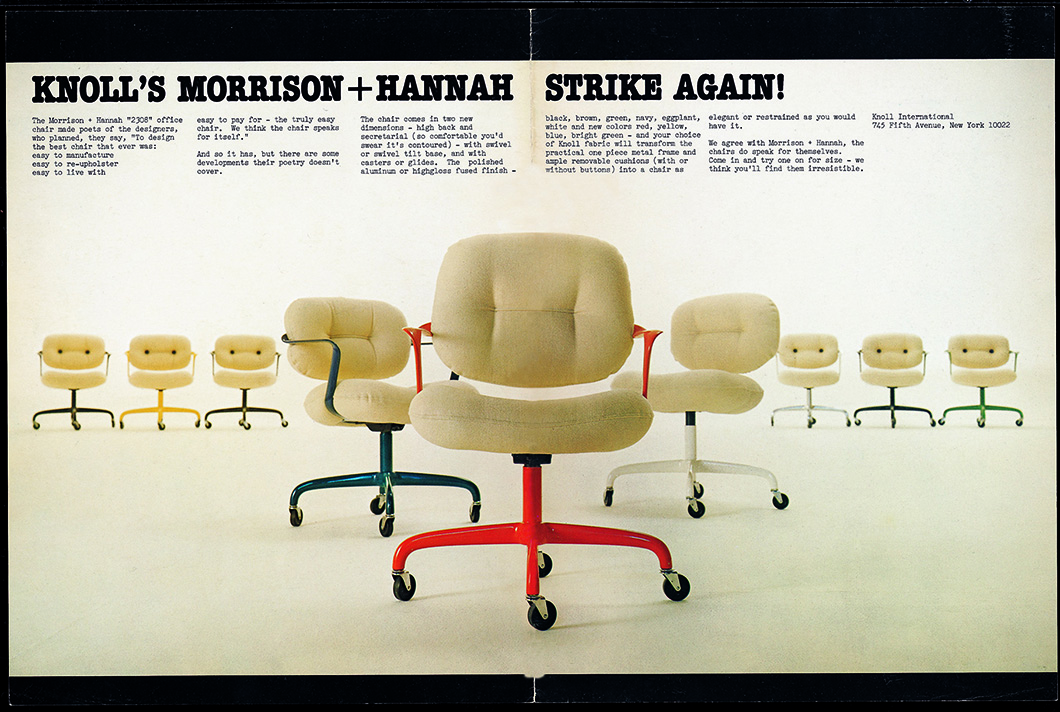

The 2308 swivel office chair, designed by Bruce Hannah and Andrew Morrison. Images from the Knoll Archive.

When it came to the rapidly expanding product category of office seating, Osborne was determined to put Knoll at the forefront. His approach was considered and multipronged. “It’s a combination of functional constraints, searching out the different minds, developing expertise and knowledge in different materials, and putting the three together,” he said.

Osborne worked with designers Bruce Hannah and Andrew Morrison to develop task chair designs as well as a "neutral" office system that "reinforces the function of the space" in a manner that, true to Knoll, placed a greater emphasis on encouraging individual expression than on the furniture itself.

“It’s a combination of functional constraints, searching out the different minds, developing expertise and knowledge in different materials, and putting the three together.”

—Jeff Osborne

Joseph D'Urso's sofa designs was developed with 1970s aesthetics in mind. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Collaborating with designers such as Niels Diffrient, Joseph D’Urso, Charles Gwathmey and Robert Siegel, Osborne worked hard to translate the strict modernism of Florence Knoll and the Bauhaus architects to suit the current moment.

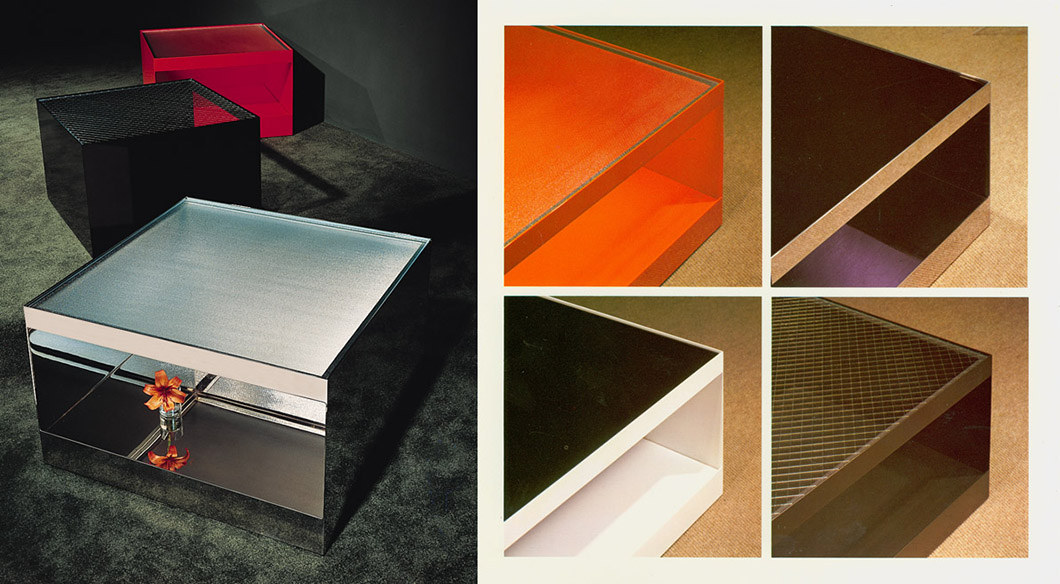

"Machines and technology are really bombarding the work environment and, functionally, the forms that support us need to respond to that," Osborne reflected, presciently. Accordingly, he championed the “hi-tech, modern thinking” of designers like Joseph D’Urso and worked with Charles Pfister to scale his sofa “very carefully to the lines of the 70s.”

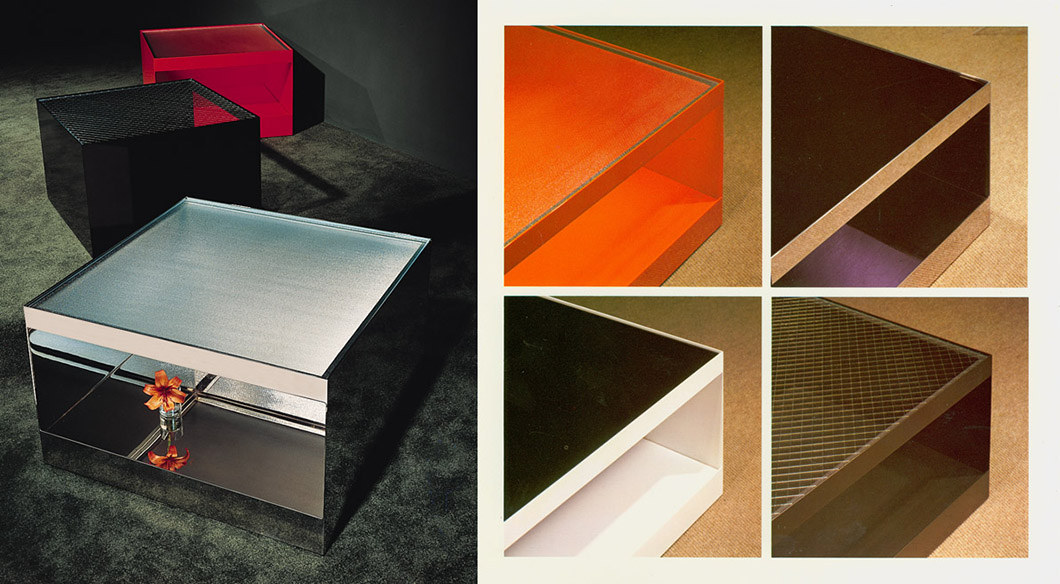

Joseph D'Urso's "high-tech" furniture included a collection of coffee tables, introduced in 1980. Images from the Knoll Archive.

Most importantly, Osborne sought to keep Knoll relevant in the constantly evolving continuum of architecture and design, molding it into a company that spoke not only to the classic modernism of prior decades but to the new ideas, technologies and concerns that were emerging in the present. In this regard, Osborne paid the necessary attention to detail, but always had an eye on the bigger picture.

“Every piece we do does not have to be a breakthrough,” he said. “It’s really the whole collection that works, so you can put together quiet pieces with strong pieces and have a balanced interior.”

With his holistic, uncompromising vision and his considered approach to every project he touched, Jeff Osborne was a beloved voice in the field of design. After his time Knoll, he worked as a design consultant for countless clients; perhaps one of his proudest roles was as a founding board member of Publicolor, a New York-based non-profit that uses design education to guide at-risk students through high school and college.