This year, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) awarded Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi the 2016 AIA Gold Medal, which acknowledges influential contributions to the theory and practice of architecture. The husband-wife team, credited with rocking the Modernist boat and heralding the design era known as Postmodernism, is the first pair to receive the Gold Medal, the AIA's highest honor. The architects forged a divergent path from the architectural dogmatism of the 1960s, investigating form, function and ornament across scales, from city to suburb to building and, with Knoll, to chair.

"Through a lifetime of inseparable collaboration, they changed the way we look at buildings and cities," 2015 AIA President Elizabeth Chu Richter said in the press release. "Anything that is great in architecture today has been influenced in one way or another by their work." As with buildings and cities, so too with chairs: today, the witty Venturi Collection remains an insightful and intelligent comment on history, form and function in the design and manufacture of furniture.

Denise Scott Brown in Las Vegas, c. 1972. Photograph by Robert Venturi. Image courtesy of VSBA.

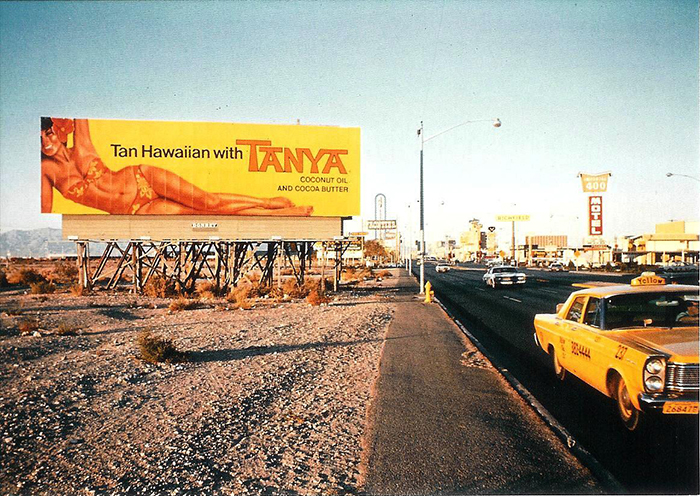

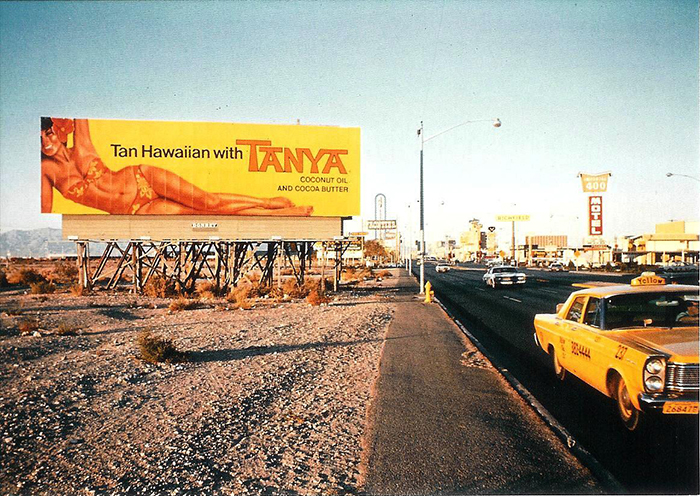

Much has been written about just how Venturi and Scott Brown defined a new wave of architectural theory and practice. Famously, their 1972 treatise Learning from Las Vegas declared, “Enough with Modernism!” and legitimized strip malls, shopping centers and fly-by signage as legitimate architectural references. To Miesian quips of “Less is more,” Scott Brown and Venturi countered, “Less is a bore.”

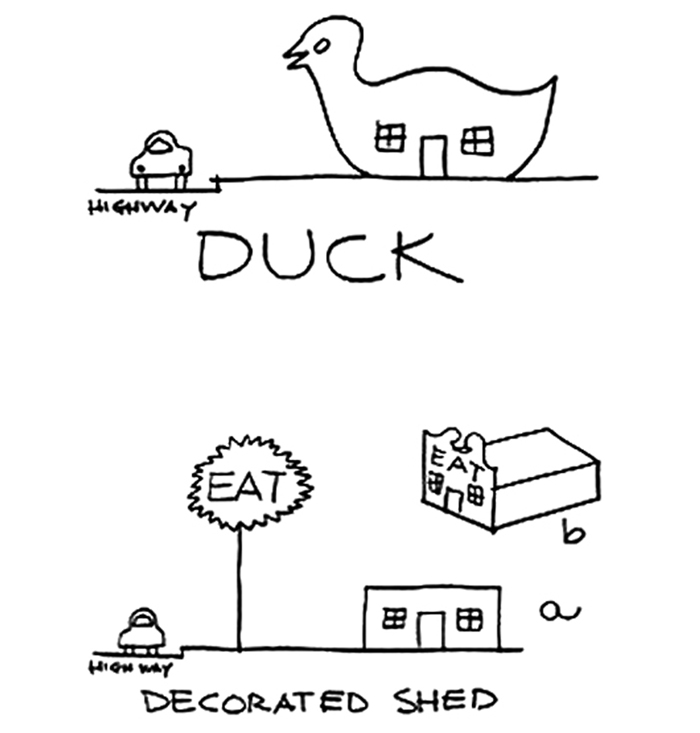

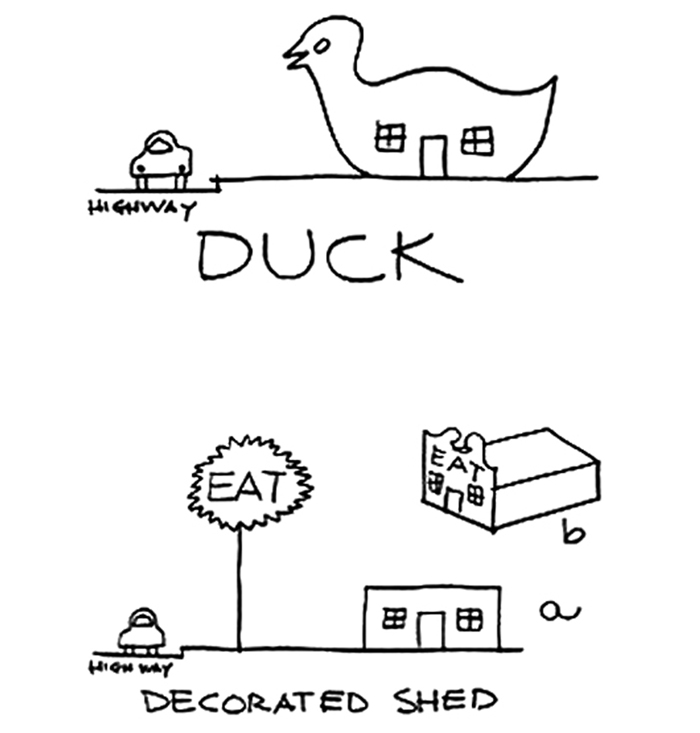

Central to Scott Brown's and Venturi's critique of Modernism was the idea that design had lost its way. The book's famed distinction between “ducks” and “decorated sheds” challenged the modernist rejection of ornament, arguing that, historically, ornament has served a function. “Function,” Scott Brown offered by way of explanation, “is a much broader topic than the Modernists thought of it.”

Graphic depiction of a "duck" and "decorated shed" by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi. Image used with permission from Learning From Las Vegas.

The new perspective split the architectural community's major figures. The Whites—Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk and Michael Graves—came to the defense of the old guard modernists, while the Greys—Steven Izenour, Robert A.M. Stern, Charles Moore and Allan Greenberg—rallied behind Scott Brown and Venturi’s ideas.

“Function is a much broader topic than the Modernists thought of it.”

—Denise Scott Brown

“Tanya” billboard, the cover image on both editions of Learning from Las Vegas. Photograph by Denise Scott Brown. Image courtesy of VSBA.

For the Greys, the Learning from Las Vegas manifesto necessitated the creation of a new culture of applied architectural research, modeled after the kind Scott Brown and Venturi had used to decode the Las Vegas strip. Reflecting on its impact 43 years after the fact, Scott Brown told Dezeen: “It has made research something much closer to design, to applied research, than what you did as research before, which was kind of historical.”

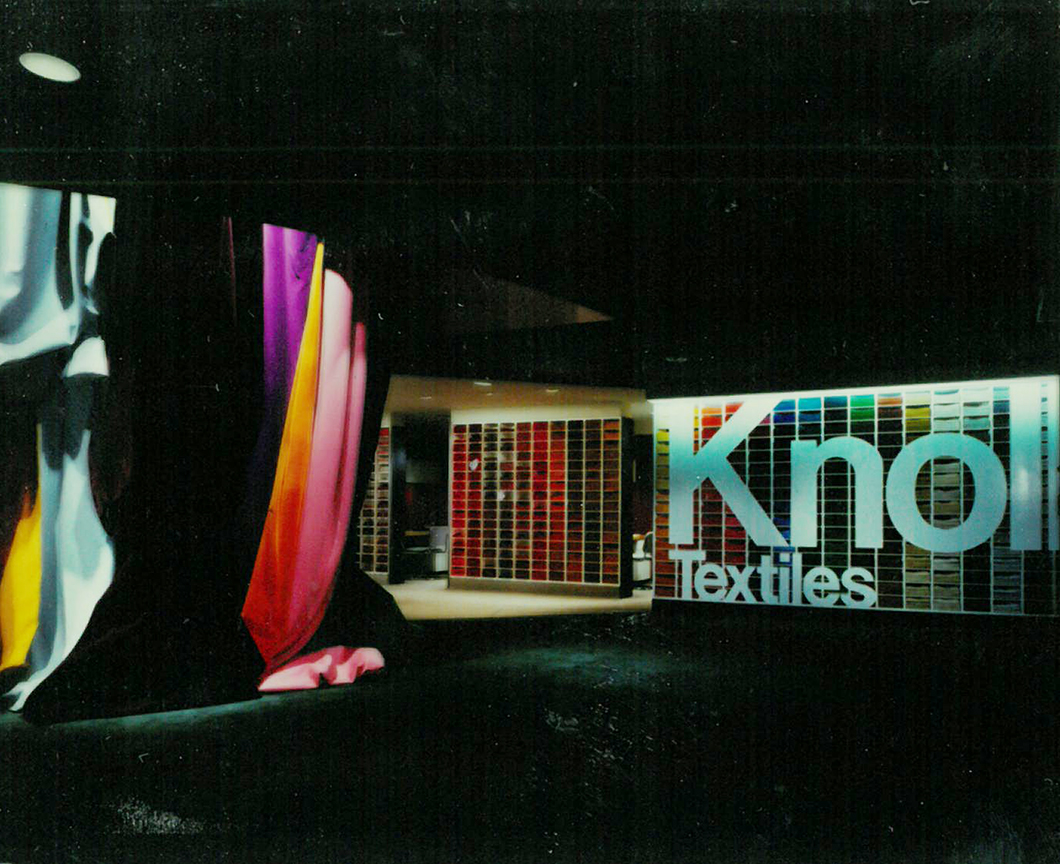

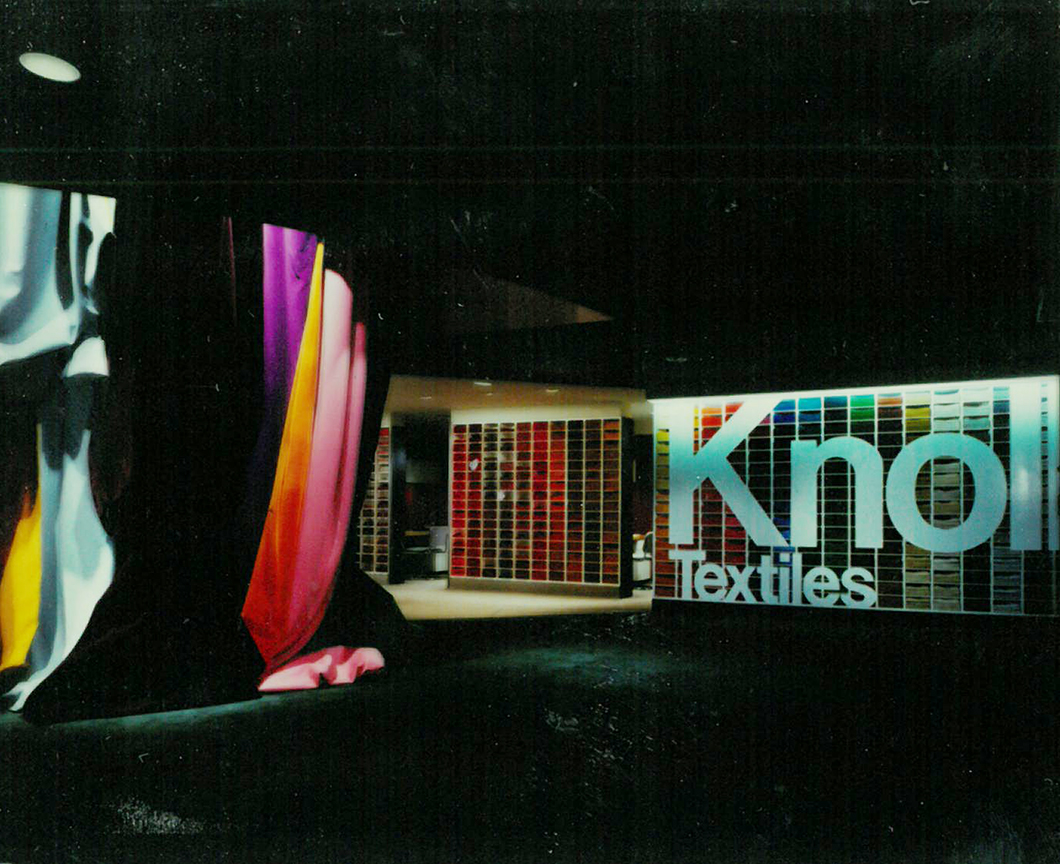

Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown's redesign of the Knoll Madison Avenue showroom, c. 1980. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Knoll, a company that had distinguished itself as an advocate for better work and life through design, saw groundbreaking thinkers in Venturi Associates. Knoll first asked Scott Brown and Venturi to redesign its 655 Madison Avenue showroom in 1980. In response, the architects dramatically reinterpreted Florence Knoll’s gridded textile wall, draping a color wheel of textile upholsteries from the ceiling to make a dramatic, flowing form of structural drapery. Throughout the showroom, a dark, upholstered backdrop heightened the visual impact of Brown and Venturi’s use of pattern, texture and ornamentation.

“What I propose is a series of chairs, tables, and bureaus that adapt a series of historical styles involving wit, variety, and industrial process, and consisting of a flat profile in a decorative shape.”

—Robert Venturi

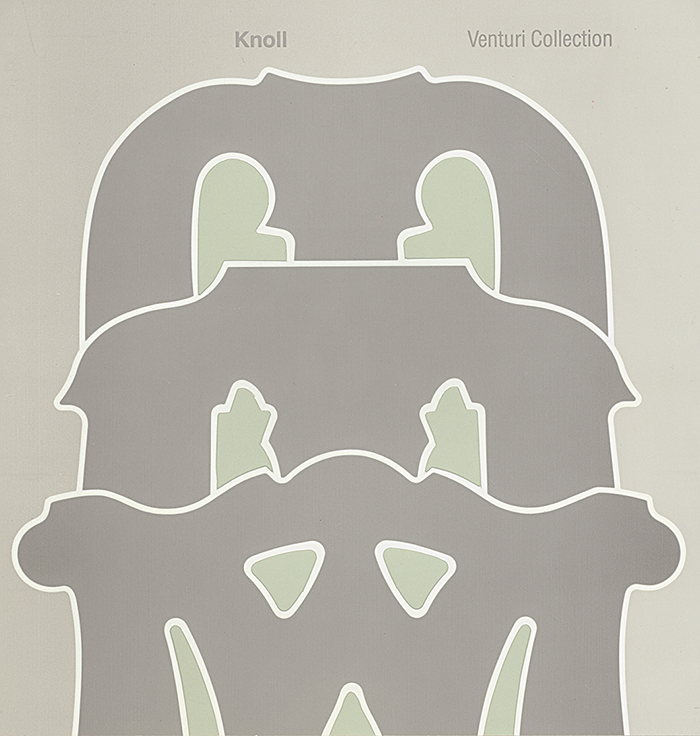

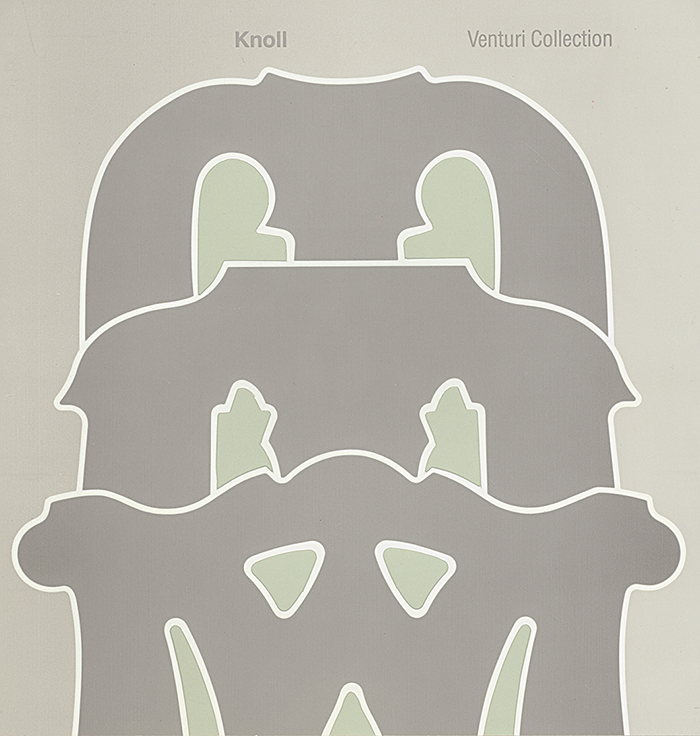

Knoll brochure for The Venturi Collection, c. 1984. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Four years later, Knoll asked Robert Venturi to design a collection of furniture. In fact, Venturi had begun sketching ideas for his now signature collection as early as 1976, and he leapt at the opportunity to realize them with the product development and manufacturing resources that Knoll could provide. In a letter to the Knoll development team, Venturi explained his vision: “What I propose is a series of chairs, tables and bureaus that adapt a series of historical styles involving wit, variety and industrial process, and consisting of a flat profile in a decorative shape.” He concluded by saying that he hoped the collection would facilitate “an evolution with the Modern Movement.”

Photographic negatives of four of the chairs in The Venturi Collection, c. 1984. Image from the Knoll Archive.

In May 1984, Knoll introduced a series of five chairs, which, taken together, presented a postmodern twist on the history of the chair: the Queen Anne, Chippendale, Sheraton, Empire and Art Deco. Three tables and a sofa completed the original collection. Soon after, Venturi introduced four more chairs, which were available only through special order. Although the chairs were Venturi's pet project, Scott Brown was also involved in the design process.

“These are wonderful contradictions, aren’t they?”

—Denise Scott Brown

Robert Venturi with The Venturi Collection, c. 1984. Image from the Knoll Archive.

In its material, the Venturi Collection continues the modernist preoccupation with molded plywood, especially when considered alongside the developments made by Thonet, Eames and Saarinen in the decades prior. But in contrast, the chairs’ final stamped-out silhouettes can also be viewed as examples of historical pastiche. For the design, Venturi insisted that the laminated plywood layers be exposed along the chair edge as a reference to, or—to use Scott Brown and Venturi’s terminology—a “symbol” of the chair’s industrial manufacture.

Most provocatively, the chairs introduced an element of complexity by contrasting historically-derived forms with a mass-produced methodology. According to Scott Brown, such disparities were to be celebrated. She asked, rhetorically, “These are wonderful contradictions, aren’t they?”

“Grandmother” fabric by Robert Venturi, c. 1984. Image from the Knoll Archive.

The collection was accompanied by a small selection of custom fabrics. Venturi first developed the patterned plastic laminate fabric known as “Grandmother” after an upholstery seen in his grandmother’s house in Pennsylvania. Venturi had copyrighted his interpretation of the pattern in 1983, although subsequently licensed it to Knoll for use with his chairs. On the other hand, Tapestry, another patterned upholstery fabric, was specifically developed by Venturi for use on the Venturi Collection sofa.

“I think there was a lot that was learned [...] from Postmodernism, but there is still a lot to be learned.”

—Denise Scott Brown

Three of the five chairs in The Venturi Collection, c. 1984. Image from the Knoll Archive.

“We’ve turned [Postmodernism] into learning about how decoration works along with other things, or studying cultural values in relation to design," Scott Brown reflected. "I think there was a lot that was learned in that way from Postmodernism, but there is still a lot to be learned.”

Robert Venturi in Las Vegas, c. 1972. Photograph by Denise Scott Brown. Image courtesy of VSBA.

All images unless otherwise noted are from the Knoll Archive or courtesy of VSBA.

Quotations attributed to Denise Scott Brown are from an interview conducted by Dezeen on August 18, 2015.