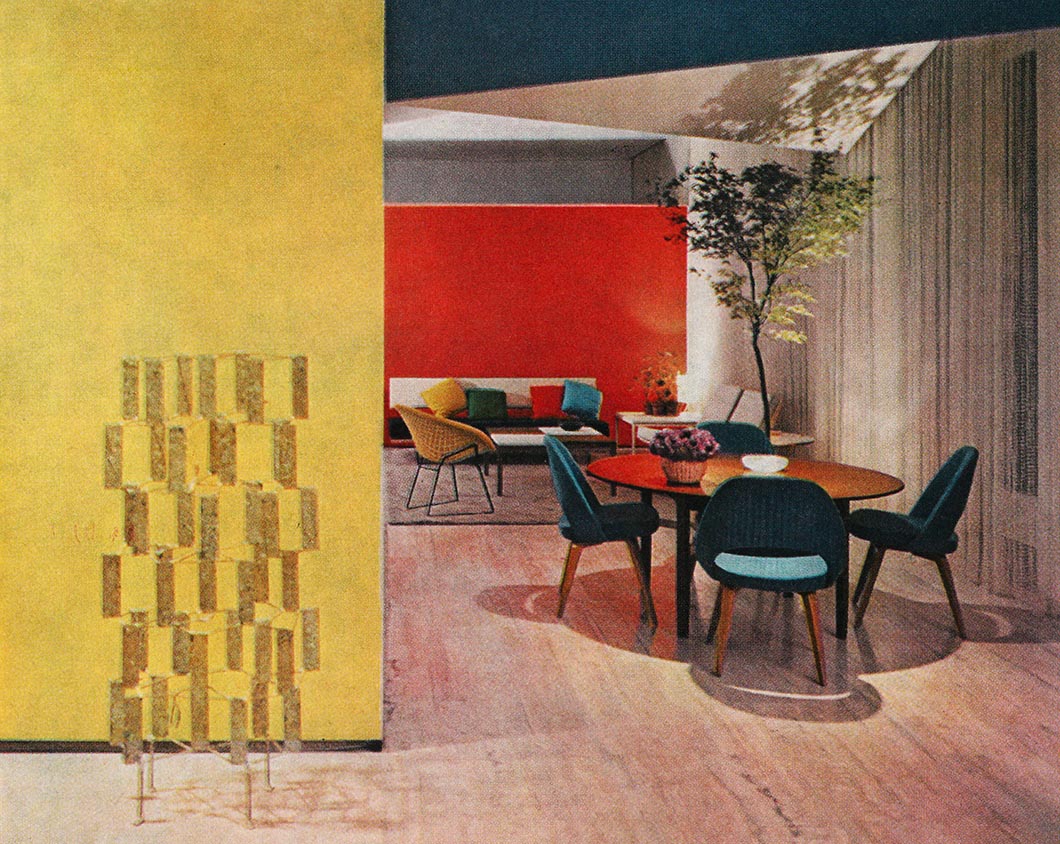

To their collections for Knoll, both Harry Bertoia and Eero Saarinen brought a keen understanding of material and structure, carried over from their respective fields of expertise. While Bertoia’s celebrated wire chairs followed years of experimentation in metal sculpture and jewelry, Saarinen’s efforts to create furniture supported by slim pedestals echoed the aesthetics of his grander architectural projects. And although the two first met at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in the late 1930s, it was only after architect and sculptor began to experiment in furniture design at Knoll did they finally combine their talents.

A happy marriage of wire and curve: Bertoia's Diamond Chairs around a Saarinen Pedestal Dining Table. Image from the Knoll Archive.

It was only a matter of time before they would pair their inimitable styles, and it began in 1952, the year Bertoia had his new wire chairs displayed in the Knoll New York showroom for the first time. “Florence Knoll encouraged Harry to include some of his sculptures in the showroom for the opening party,” recalled Celia Bertoia, the sculptor’s daughter. “Eero Saarinen came to this gathering and noticed some of the screen-based works.” And so began a succession of collaborations between the architect and the artist.

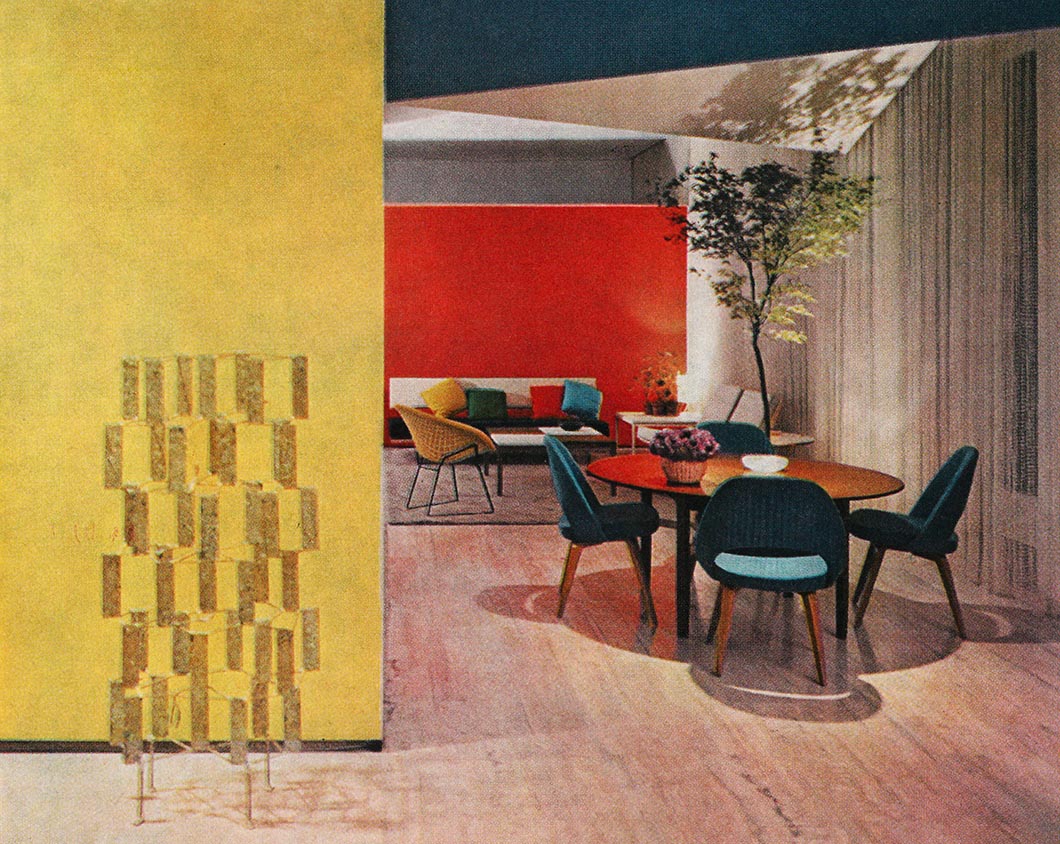

Harry Bertoia's sculptures have become a mainstay of Knoll showrooms after Florence Knoll's initial suggestion. Image from the Knoll Archive.

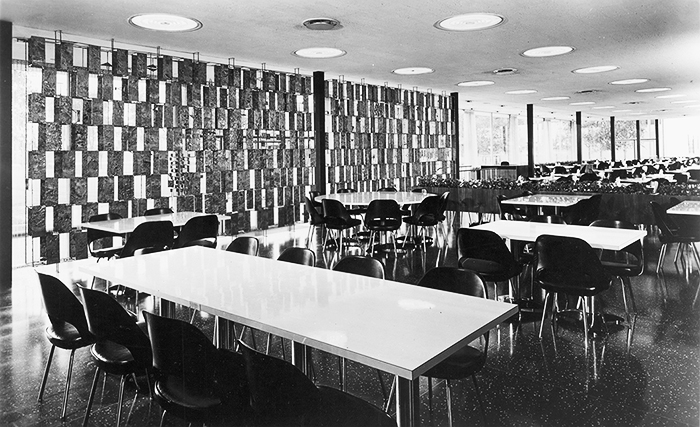

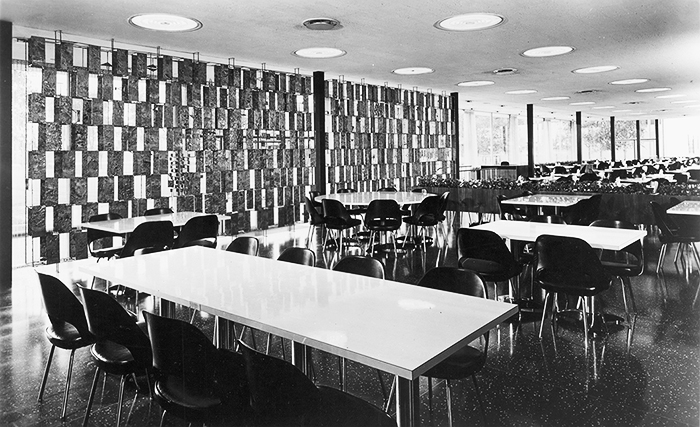

A year after the opening, Saarinen commissioned Bertoia to create a large panel sculpture for his ongoing project in Warren, Michigan, the General Motors Technical Center. Bertoia’s sculpture took the form of a 37-foot-long wall separator that marked the boundary of a cafeteria on a large, open plan floor of the facility. Soon after, the sculptor was tapped to complete a similar project, this time creating a 70-foot sculpture and wire cloud for the Manufacturers Hanover Trust Building at 510 Fifth Avenue in New York. Designed by modernist Gordon Bunshaft, then a partner at architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the tower and sculpture remain intact today, although the building’s function has since changed.

The cafeteria at the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, with Saarinen Executive Armless Chairs in front of Bertoia's 37-foot wall separator. Image from the Knoll Archive.

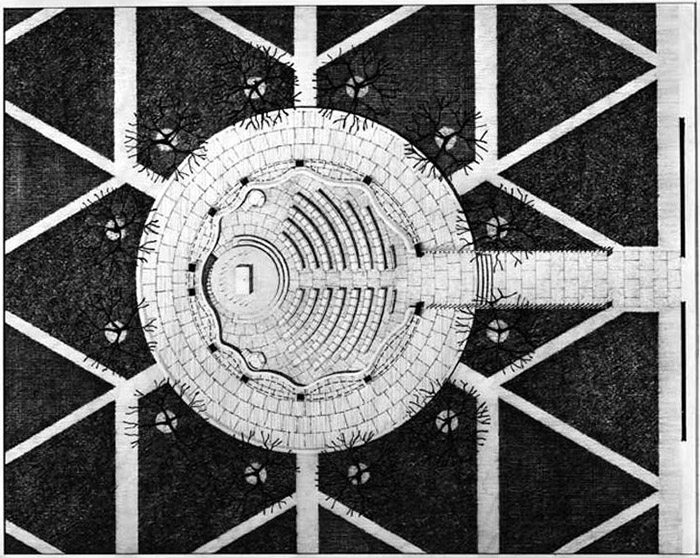

While Saarinen went on to design a number of commercial projects, it was a more unique commission that eventually led to the most exquisite collaboration between the two Knoll designers—the Kresge auditorium and chapel at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. In attempt to strengthen the social cohesion of the university, MIT sought an auditorium in which students and faculty could convene for formal events as well as a non-denominational space of reflection in which weddings and memorials could be held.

“This circular shape also seemed right in plan, for this was basically a chapel where the individual could come and pray and he would be in intimate contact with the altar.”

—Eero Saarinen

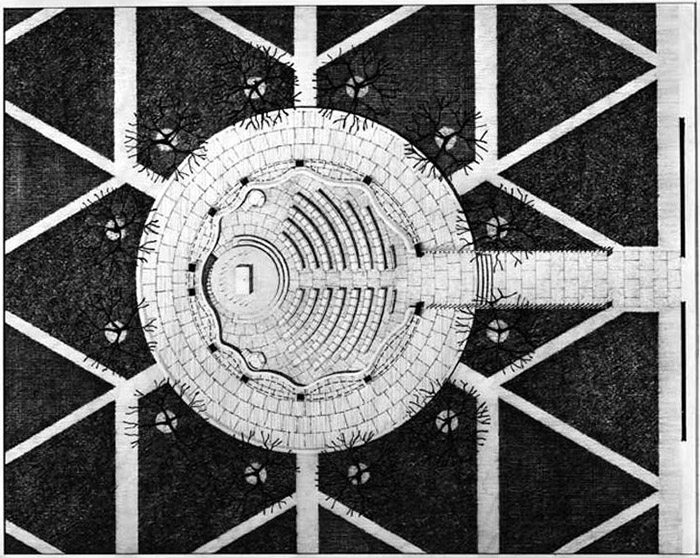

Plan drawing of the cylindrical Kresge Chapel at MIT, designed by Eero Saarinen. Image courtesy of the MIT Libraries.

Saarinen, ever a lover of curved constructions, devised a simple oval expanse of green, within which the two structures would sit. Each building had its own simple but distinctive contours—the auditorium was defined by a sweeping concrete roof that represented one-eighth of a sphere, while the chapel took the form of a simple cylinder. It was the latter building, shocking in its windowless simplicity, that sparked the most controversy.

Saarinen's curved auditorium and chapel under construction at MIT. Image courtesy of the MIT Libraries.

In spite of the contention it sparked, the design of the corner-less holy space seemed entirely natural to its architect. “This circular shape also seemed right in plan,” Saarinen later wrote. “For this was basically a chapel where the individual could come and pray and he would be in intimate contact with the altar.”

Modernist heavyweight Louis Kahn confirmed the intimate essence of the space. “The essential thing, you see, is that the chapel is a personal ritual, and that it is not a set ritual, and it is from this that you get the form,” he said in a 1959 lecture. “The form is derived from this, and not from changing, modifying, making modern that which was already set for you as a chapel.”

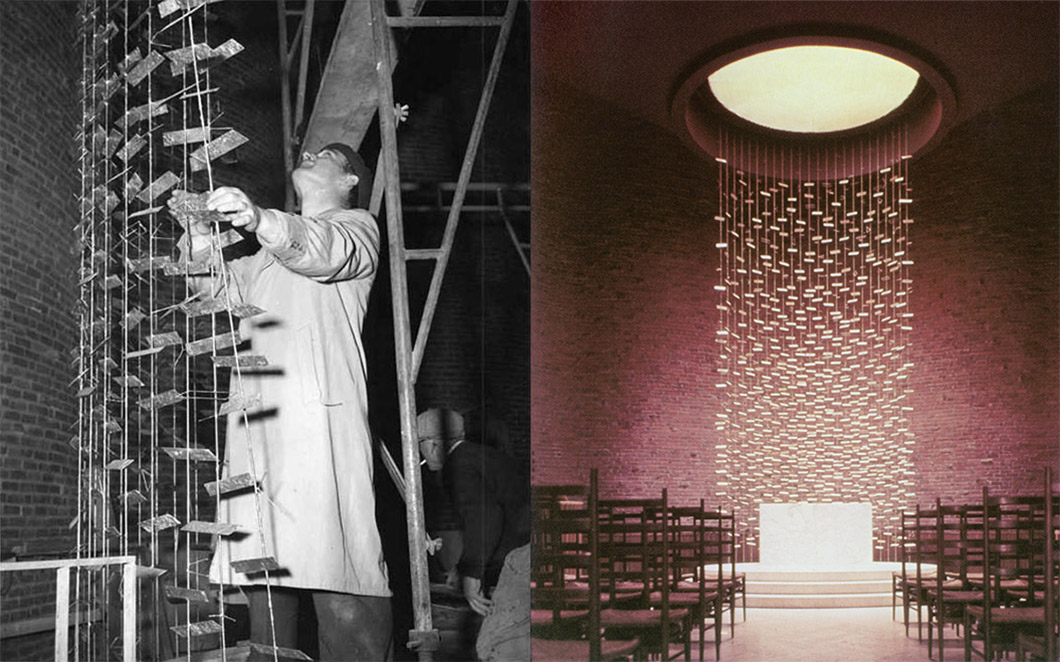

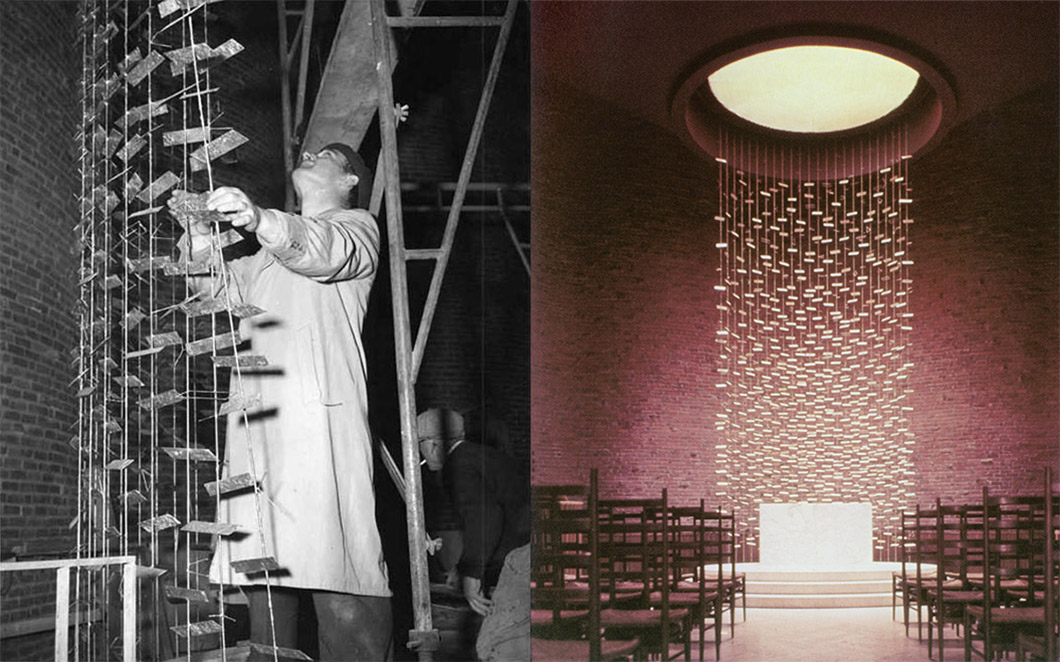

Left: Bertoia adjusts the wire altarpiece of the Kresge Chapel. Image courtesy of the MIT Libraries. Right: Interior view of the Kresge Chapel, with the alterpiece lit by sunlight through the oculus. Image from the Knoll Archive.

In its invitation to commence a private ritual in a public space, the altar of the Kresge Chapel hinges on the simple drama of the wire sculpture that occupies its center. A stunning curtain of small, bronze-coated metal rectangles, held afloat by 20 pieces of taut wire, the altarpiece is undeniably spiritual.

“Eero thought of Harry when time for the MIT Chapel came,” recalled Celia Bertoia, the sculptor’s daughter. “He explained the skylight and Harry came up with different designs, but they knew that they wanted to use that one source of light, to create the appearance of rays of light coming from the heavens.”

“Eero explained the skylight and Harry came up with different designs, but they knew that they wanted to use that one source of light, to create the appearance of rays of light coming from the heavens.”

—Celia Bertoia

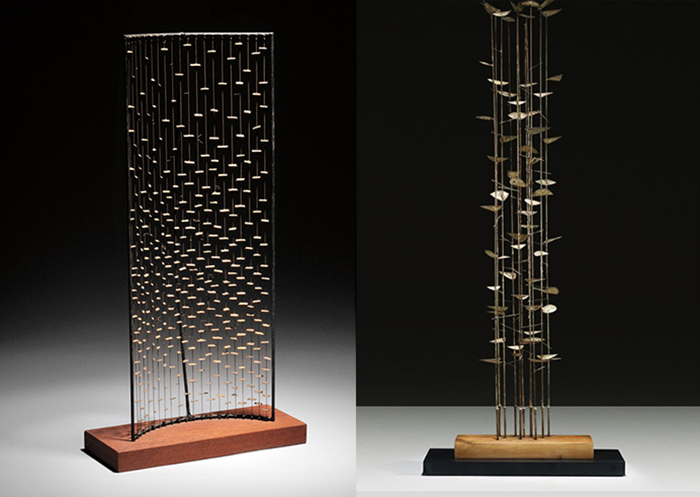

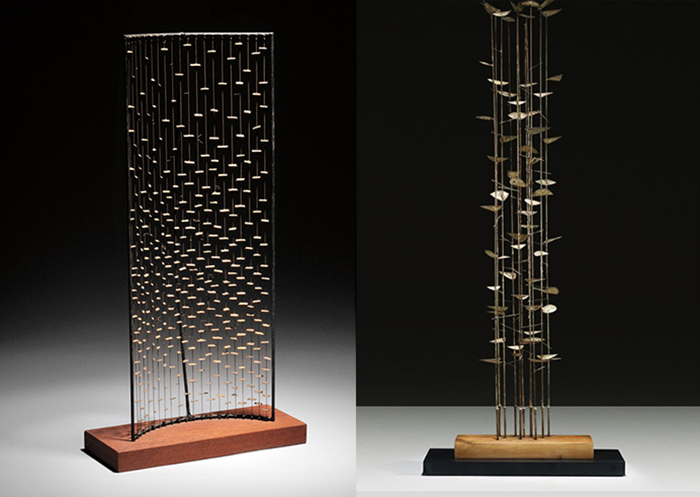

Small-scale study maquettes made by Harry Bertoia for the altarpiece of the Kresge Chapel. Images courtesy of Skinner, Inc. and Wright.

Saarinen later recalled the inspiration behind the focal point of his chapel. “I have always remembered one night on my travels as a student when I sat in a mountain village in Sparta,” he wrote. “There was bright moonlight over head and then there was a soft, hushed secondary light around the horizon. That sort of bilateral lighting seemed best to achieve this other-worldly sense. Thus, the central light would come from above the altar—dramatized by the shimmering golden screen by Harry Bertoia—and the secondary light would be light reflected up from the surrounding moat through the arches.”

The bronze-coated metal rectangles of Bertoia's altarpiece glimmer in the natural light. Images courtesy of Jim Stephenson.

Bertoia was determined to capture the sublime quality of the light that Saarinen sought, and did so by giving the surfaces of the altarpiece a rough texture. “As he was installing the piece he wanted to get it at a certain tension,” Celia explained. “He would pluck the wires almost like a violin to make sure they were at the correct tension. It was an unusual design for a sculpture because it has no base, it was simply these wires stretched in space. But Harry was all about space; there’s that famous quote about his chairs and he worked with the same concept in his sculptures. There’s very little material there—it’s just a few wires and metal, but a lot of space and light.”

Indeed, the sculptor famously likened his furniture design for Knoll to his artistic endeavors, specifically citing their shared levity. “They are mainly made of air, like sculpture,” he said of his chairs. “Space passes right through them.”

The subtle drama of wire and curve in the daylight: Bertoia's Bird Chair and Saarinen's Pedestal Coffee Table. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Light and air, more than brick or metal, might be the true building materials of the Kresge Chapel. “As your eyes adjust to the light, you notice the undulating brickwork,” explained architectural photographer Jim Stephenson after a recent visit to the site. “The sculpture draping down from the rooflight catches the eye. The acoustics change, the air temperature changes, the whole atmosphere is different, and you’ve only moved a step or two.”

The interior periphery of the Kresge Chapel at MIT, with its undulating brick surface. Image courtesy of Jim Stephenson.

“The brickwork is dark, heavy and grounded, tactile and tectonic. In contrast, Bertoia’s sculpture is the complete opposite—it’s light and ethereal.”

—Jim Stephenson

Still, brick and metal play a crucial part in the overall feeling of encapsulation. “The circular chapel of the building is so incredibly solid,” said Stephenson. “The brickwork is dark, heavy and grounded, tactile and tectonic. In contrast, Bertoia’s sculpture is the complete opposite—it’s light and ethereal. It appears fleeting and changeable and the sun moves around and shines through the skylight. To have two elements, in a building with very few elements, be so different without being jarring is a real skill and now, of course, you can’t imagine one without the other.”

The interior space of the Kresge Chapel at MIT, suited to personal ritual and quiet contemplation. Image courtesy of Jim Stephenson.

The appropriate material and tectonic asceticism of the Kresge Chapel at MIT is perhaps what makes it such an icon of modern design, as well as evidence of the harmonic possibilities within the Knoll constellation. But perhaps it was Eero Saarinen who, in a few humble words, explained it best. “However, I am happy with the interior of the chapel,” he said. “I think we managed to make it a place where an individual can contemplate things larger than himself.”