In all its optimism and predictability, prefabricated housing was once the hopeful icon of a modern future—with floor plans that laid out a scheme of public harmony and glossy mail-order catalogs that presented placid scenes of domestic living. But since its zenith in the early years of the twentieth century, the glowing possibilities of the prefabricated abode have long since dimmed. Now preferring the bespoke to the standardized, homeowners have deemed the housing typology, with its rigidly defined comforts, a thing of the past. But for Karen Valentine and Bob Coscarelli, one mid-century prefab design in Michigan City, Indiana, spoke not of uniformity, but uniqueness.

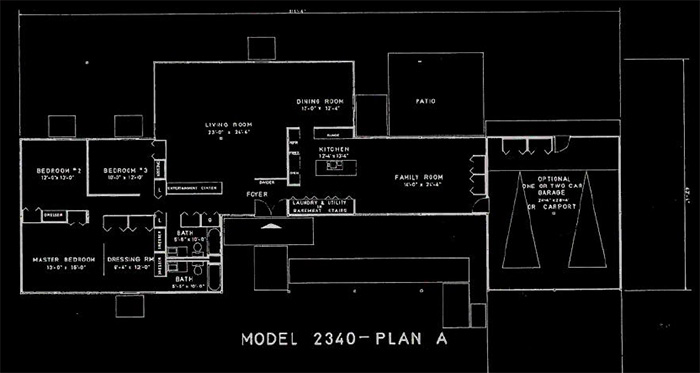

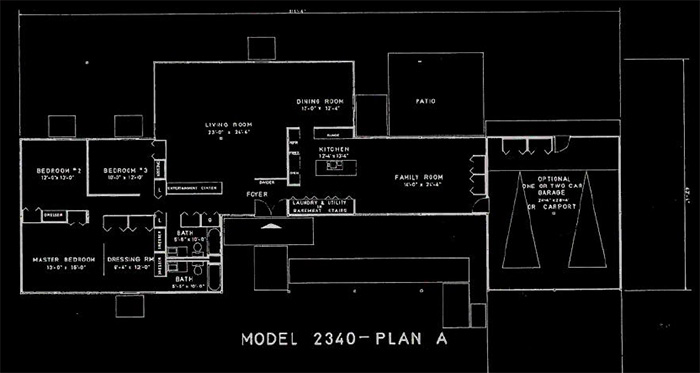

Plan of the Alside Homes prefabricated house, Model 2340. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Although named after its original owners, the Frost House was formally referred to as Model 2340 by the Alside Homes Corporation, the Ohio-based company that conceived the design in the late 1950s and patented it soon after. A subsidiary of Alside, Inc., Alside Homes offered "the industry’s first manufactured aluminum home" to the American public, veering away from the timber constructions of prefabs past and towards the sleek industrial materials championed by architects of the International Style.

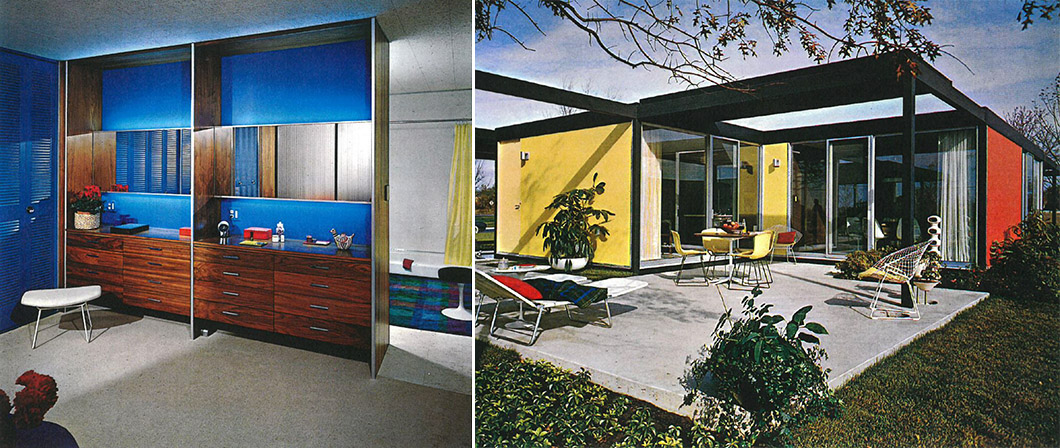

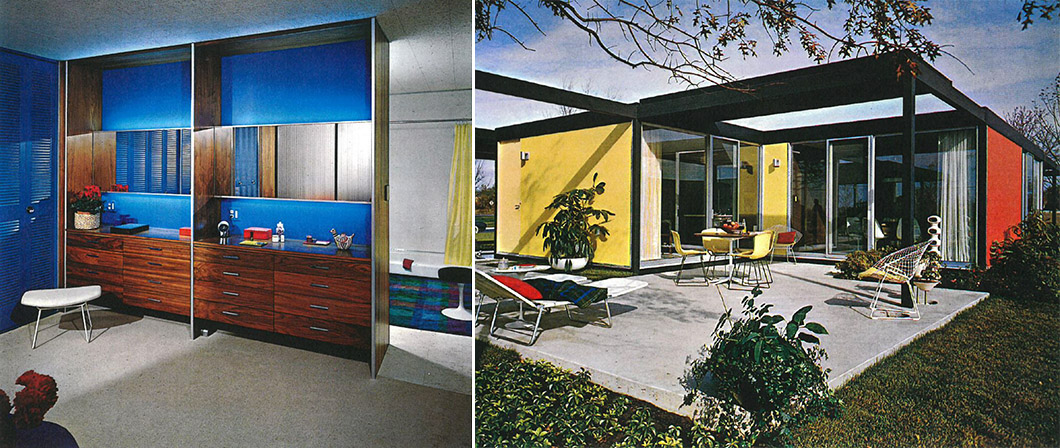

The exterior of the Frost House is comprised of a glass and aluminum curtain wall mounted on steel supports. Photograph by Bob Coscarelli.

The metal parts were not only easy to ship, but easy to reconfigure—aluminum panels could be colored to the owner’s preference and placed in different sequences along the façade, with glass panes in-between.

"A patent-pending modular steel framing system permits a new degree of spacious open planning," proclaimed the brochure, which showcased a range of house models designed by architect Emil Tessin. But while Alside set its sights on a rate of 200 houses built per day, the ambitious scheme never took off, leaving only a smattering of the steel-framed homes across the country.

A Womb Chair and Ottoman, designed by Eero Saarinen, in the Frost House living room. Photograph by Bob Coscarelli.

Since the corporation has receded into obscurity, brochures and magazine features from the time help the new owners of the Frost House determine its past. In a process that is part renovation, part historical research, Coscarelli and Valentine have been putting together pieces of the puzzle while working to restore the original details—from the wall colors to the furniture arrangements—of their new home.

A Bertoia Side Chair in the living room of the Frost House. Photograph by Bob Coscarelli..

"One such piece [of the puzzle] revealed to us that Dr. Frost had actually purchased the sales model, including all the Knoll display furniture," the couple explained. "The placement of the furniture essentially had never moved. We felt obligated to keep things in their environment, and moved a few pieces around to make way for additional Knoll pieces we already had and wanted to add to the collection."

“A patent-pending modular steel framing system permits a new degree of spacious open planning.”

—Alside Homes Corporation

Tulip Chairs and an oval Dining Table with a walnut top in the dining room of the Frost House. Photograph by Bob Coscarelli.

The interiors of the Frost House were designed by Paul McCobb, a furniture and industrial designer, in collaboration with Knoll. While the extent of Florence Knoll’s involvement in the project is uncertain, there appears to be a connection that belies coincidence—the father of the architect was Judge Tessin, Florence Knoll’s legal guardian in Saginaw, Michigan.

From an Alside Homes brochure: a Bertoia Bird Ottoman and Tulip Stool around the built in dresser (left); a Richard Schultz Petal Table forms the focal point of the patio. Images from the Knoll Archive.

Regardless of the circumstances that led to the decoration of the house, its spaces inevitably satisfied Alside’s claim that "clean, uncluttered wall lines lend themselves ideally to varied interior planning solutions." Indeed, the brightly hued aluminum panels that comprise the exterior of the house enclose equally vibrant interior rooms. A leather Womb Chair and an upholstered Bertoia Side Chair benefit from the light that streams in through the glass-filled segments of the façade, while the Tulip Chairs and Saarinen Dining Table in the dining room complement the mid-century modern sheen of the original paneled kitchen.

The exterior of the Frost House at dusk, with a Bertoia Diamond Chair, Saarinen Side Table and vintage Florence Knoll furniture visible through the windows. Photograph by Bob Coscarelli.

"This home is really about preservation, initially we were a little timid to change things," explained Coscarelli and Valentine, "but it is, after all, our home and we need it to work for our lifestyle. The furniture and artwork are where we are having fun—rearranging and carefully adding to, using sales brochures as reference materials and inspiration."

“This home is really about preservation, initially we were a little timid to change things, but it is, after all, our home and we need it to work for our lifestyle.”

—Karen Valentine & Bob Coscarelli

A set of 1966 Chaises and 1966 End Tables, designed by Richard Schultz, in the garden of the Frost House. Photograph by Bob Coscarelli.

An enviable collection of vintage Knoll designs still grace the home, from the parallel bar furniture of Florence Knoll in the living room to the Richard Schultz-designed 1966 Adjustable Chaises and End Tables in the garden. And as the couple, along with their rescue dog, Banksy, continues to ascertain the timeline of the Frost House, its future appears to be in good hands—proving that the gratifying potential of a prefab home can sometimes surpass its modular, predictable frame.