We never need an excuse to look at classics like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona collection or Brno chair. But we did have the opportunity to ask Kenneth Frampton—the internationally acclaimed architect, critic, and historian—some questions about these timeless pieces, their inception and influence today.

Kenneth Frampton is Ware Professor of Architecture at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. He sits on the jury of the World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize. The 2014 Prize will be announced this fall. As one of architecture’s sharpest and most prolific lecturers and writers, Frampton illuminates Mies’ chairs in the following interview.

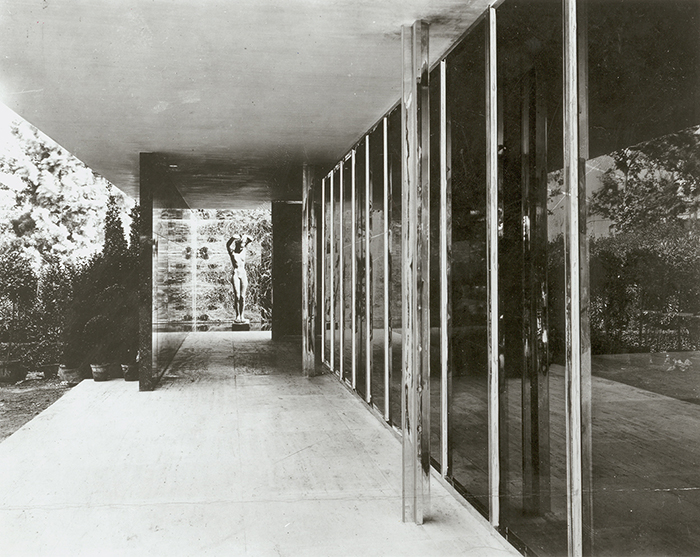

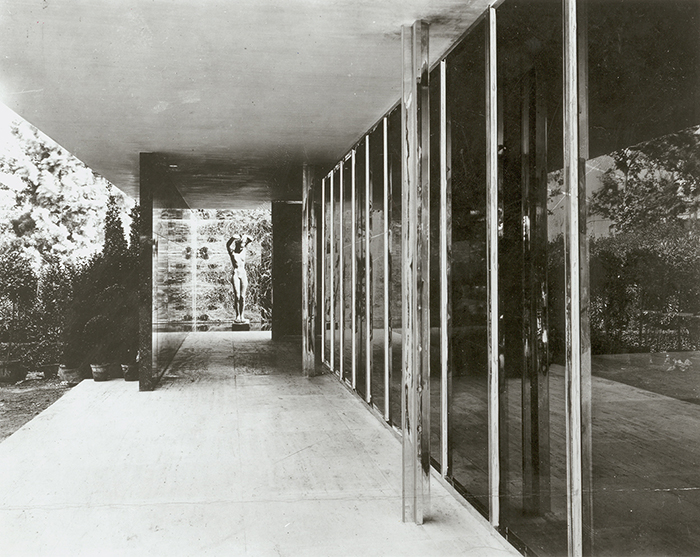

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Pavilion, 1929. Image courtesy of The Architecture & Design Study Center, The Museum of Modern Art.

“In many ways, Mies’s furniture is inseparable from the overall cultural synthesis of his work.”

—Kenneth Frampton

KNOLL INSPIRATION: The scale of a chair allows for its structure to be expressed with a clarity that would be impossible in a building. Were there structural ideas that, in furniture, Mies could resolve without compromise?

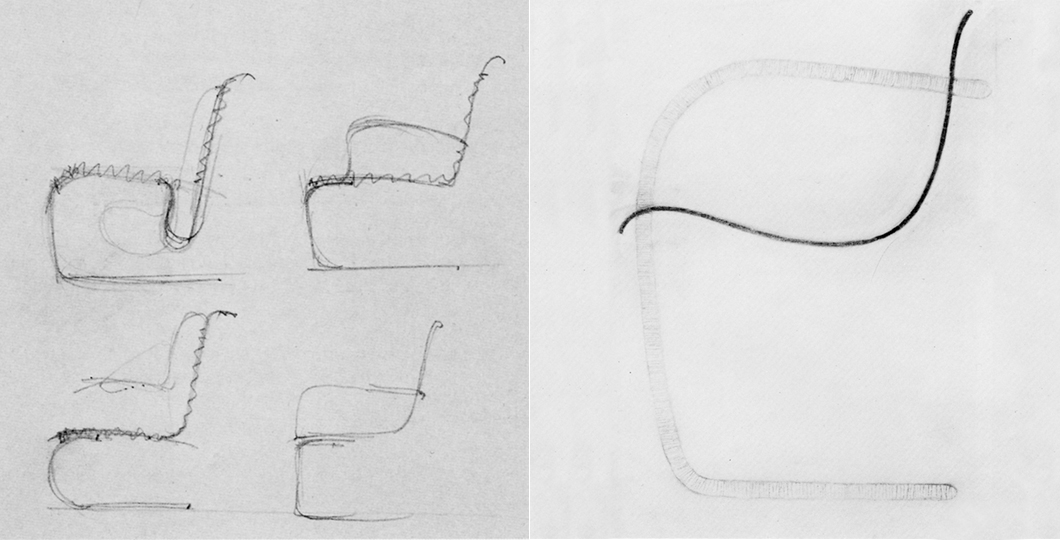

KENNETH FRAMPTON: Mies, like Marcel Breuer, made a good deal of his early reputation on the basis of his designs for a range of cantilevered chairs in chromium-plated tubular steel. Inspired by the nineteenth century standard bentwood furniture of Michel Thonet, it would be hard to imagine a simpler or purer solution to the basic proposition of a chair.

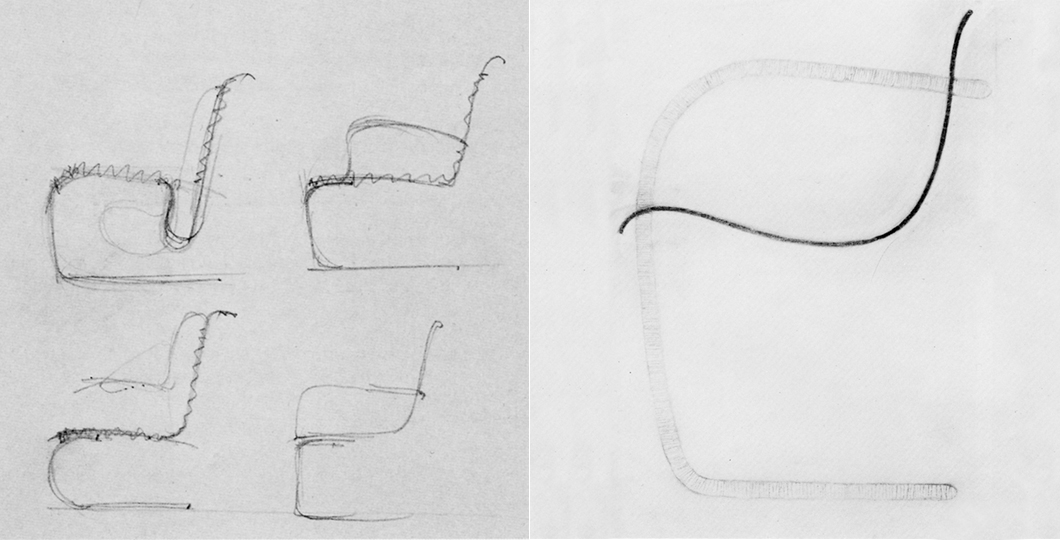

Archival sketches of the Brno Chair. Image courtesy of The Architecture & Design Study Center, The Museum of Modern Art.

Mies designed most of his furniture in the 1920s, a decade that was also pivotal for his development as an architect of buildings. How are the two scales of his design work related?

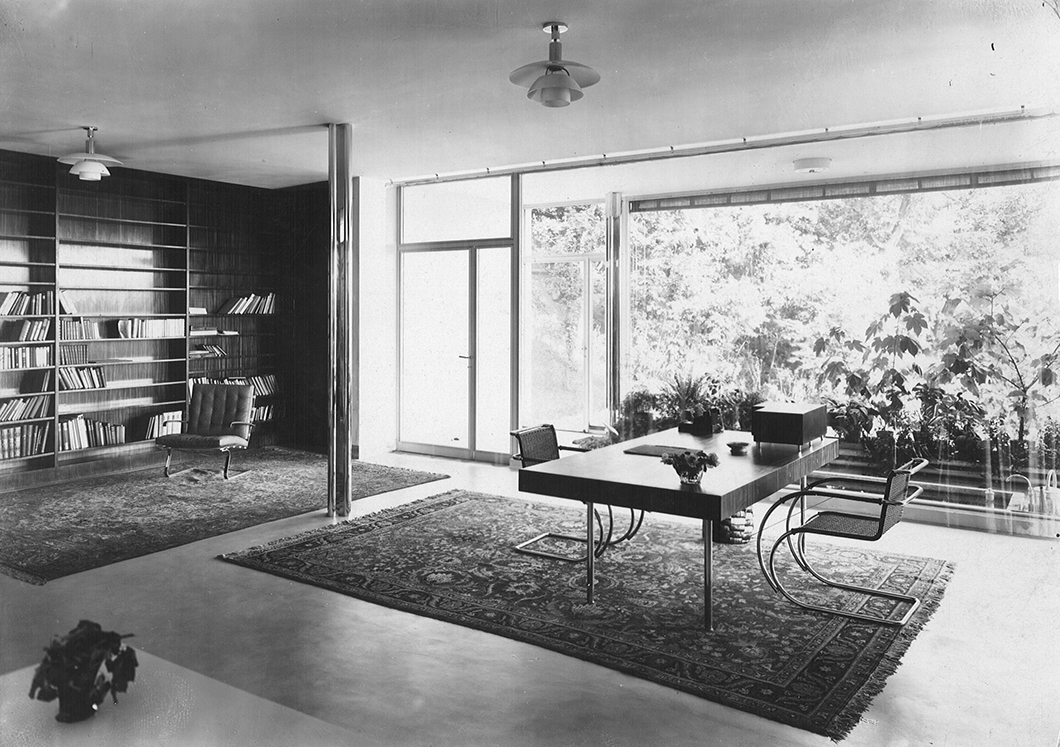

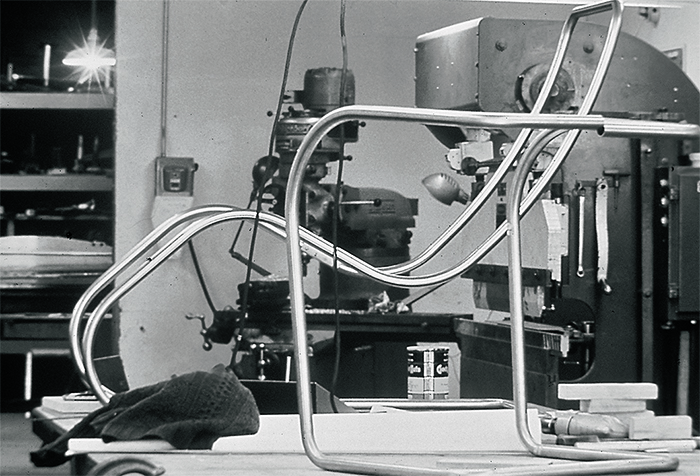

In many ways Mies’s furniture is inseparable from the overall cultural synthesis of his work. Particularly in Germany, it was as though the cult of “almost nothing” was animated and enriched by his furniture and furnishings. Exposed columnar structure is a key to Mies’s development of the free plan and, in this respect, the articulation of the MR Lounge Chair of 1931 comes closest to expressing a similar tectonic at the level of furniture. The technical description of this chair testifies to this: “steel tubes, chrome plated in seven sections connected by dowels and screws, arm tubes screwed to frame at back and fastened with brackets at bottom, two stiffening rods, nine rubber or leather straps, continuous roll and pleat cushion with plain or chequered linen cover.”

“The same material is used both for the Barcelona chair frame and for the cladding of the free-standing cruciform columns [of the Barcelona Pavilion].”

—Kenneth Frampton

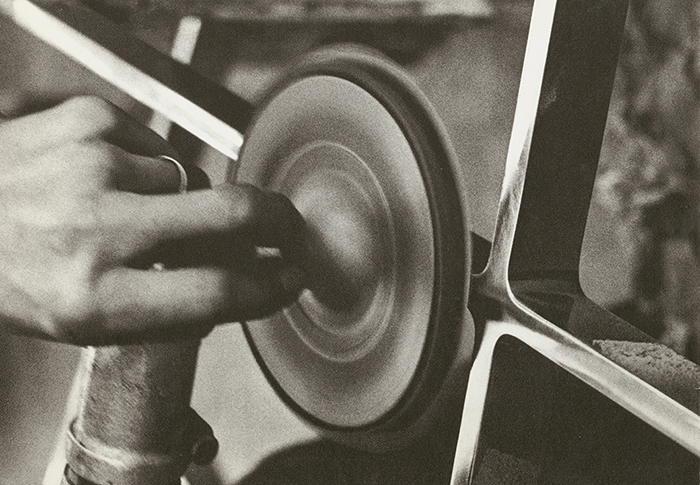

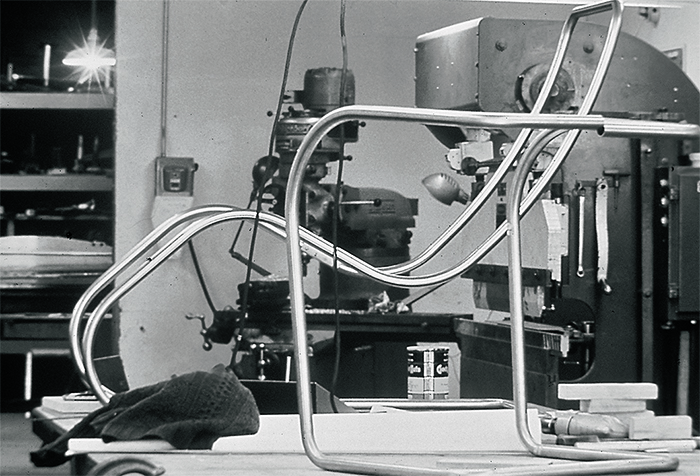

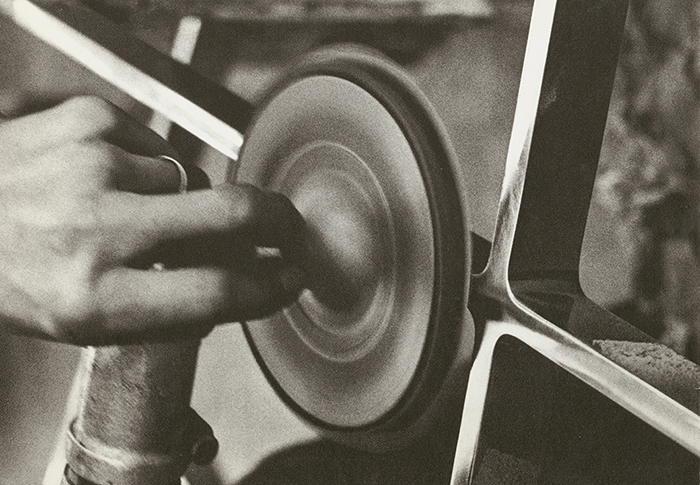

The Barcelona Chair in production at the Knoll factory in East Greenville, Pennsylvania. Image from the Knoll Archive.

You’ve written before (in your Critical History of Modern Architecture) that the Barcelona chair is a key design element of Mies' canonical Barcelona Pavilion. Can you explain?

Material in the Barcelona Pavilion is simultaneously emphasized and dematerialized. Chromium-plated steel is a key material in this regard: the same material is used both for the Barcelona Chair frame and for the cladding of the free-standing cruciform columns. In both instances, the overall effect is monumental. Flat bar steel sections of different thicknesses are used to cap the ends of the columns, and as the basic structural element of the frame of the Barcelona Chair. The so-called ‘mirror effect’ of the central space is due to a number of factors, above all the fact that the same color tone obtains in both the floor and the ceiling; the one being travertine and the other plaster. However, the dematerialization is largely due to the highlights on the chromium-plated metal, the tinting of the glass, and the proliferation of reflections throughout.

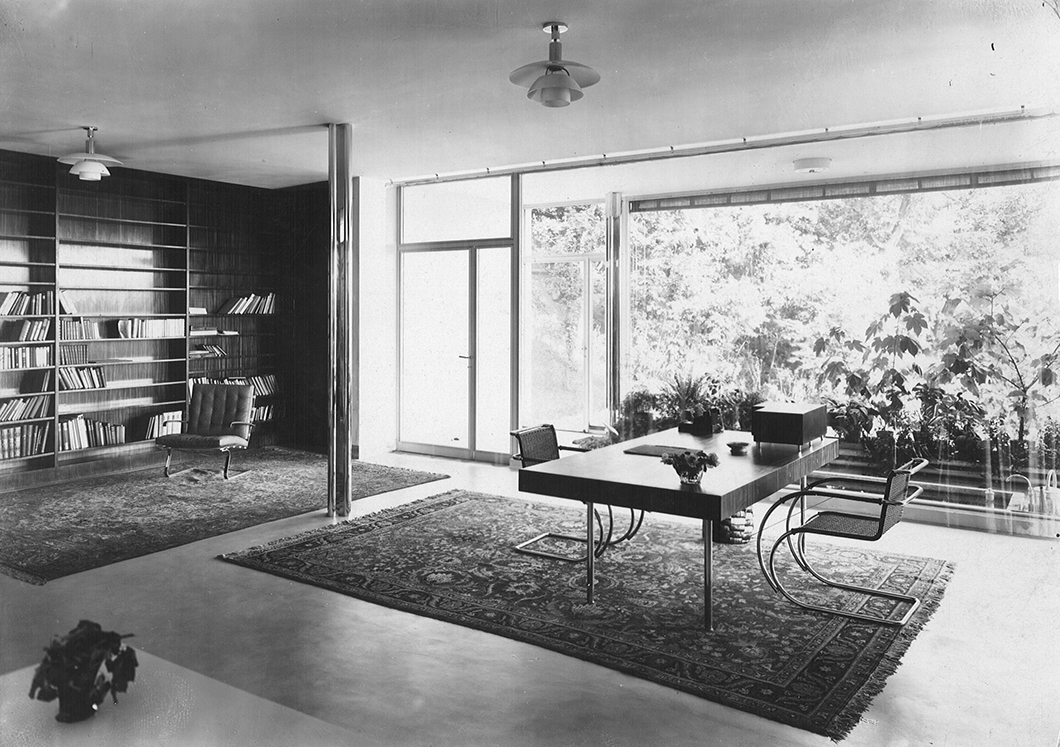

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Villa Tugendhat, 1930. Image courtesy of The Architecture & Design Study Center, The Museum of Modern Art.

Lily Reich, the German designer, worked closely with Mies for more than a decade, during the time when Mies was designing his chairs. What was her role?

Lily Reich played a crucial role in the formation of Mies’s transcendental, technological aesthetic between 1927 and 1931. The use of raw silk and brightly colored leather upholstery—red and viridian—in the Tugendhat House. All of this was surely due to Reich’s influence. We may assume she had some effect on the refinement of the furniture as well; above all surely the Tugendhat and Brno Chairs and the two versions of the chaise lounge 1931/1932 and even on the buttoned down leather couch of 1930.

“Exposed columnar structure is a key to Mies’s development of the free plan and, in this respect, the articulation of the MR Lounge Chair of 1931 comes closest to expressing a similar tectonic at the level of furniture.”

—Kenneth Frampton

Production of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's MR Chaise at the Knoll factory in East Greenville, Pennsylvania. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Can you talk about the presence of both old and new in Mies’ designs?

The primary link between Mies and the past could be summed up by the famous Werkbund term qualitätarbeig—‘quality work,’ a value transcending style he would have acquired while working for [the furniture designer] Bruno Paul. [Karl Friedrich] Schinkel is also a perennial influence on Mies throughout his career, beginning most explicitly with his project and full scale mock-up for Kröller-Müller house at Otterlo of 1912.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's MR Chaise, 1927. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Harmonizing old and new: this also is a challenge for our cities today, as they balance preservation and development.

The preservation or restoration of 20th century architecture has come increasingly to the fore in recent years, with all the attendant problems of re-use and simulating material that is no longer in production. However, the last few years has seen an increasing number of exceptional restorations, including the Zonnestraal Sanatorium and the Van Nelle factory, both in the Netherlands, which was subject to two attempts at restoration before the current renovation.

“The primary link between Mies and the past could be summed up by the famous Werkbund term qualitätarbeig—‘quality work,’ a value transcending style.”

—Kenneth Frampton

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Pavilion, 1929. Image from the Knoll Archive.

All images, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy of the Knoll Archive.