The Pan-European Living Room

OMA addresses the legacy and value of cross-border design

“Design pieces are always a result of collaborations across borders,” says Samir Bantal, director of AMO, the research arm of Rotterdam-based architecture firm OMA. Indeed, the design firm and its founder, Rem Koolhaas, have even worked with Knoll before: on the 2013 Tools for Life collection and on the ongoing, evolving "This is Knoll" display at the 2016 and 2017 Salone Internazionale del Mobile in Milan.

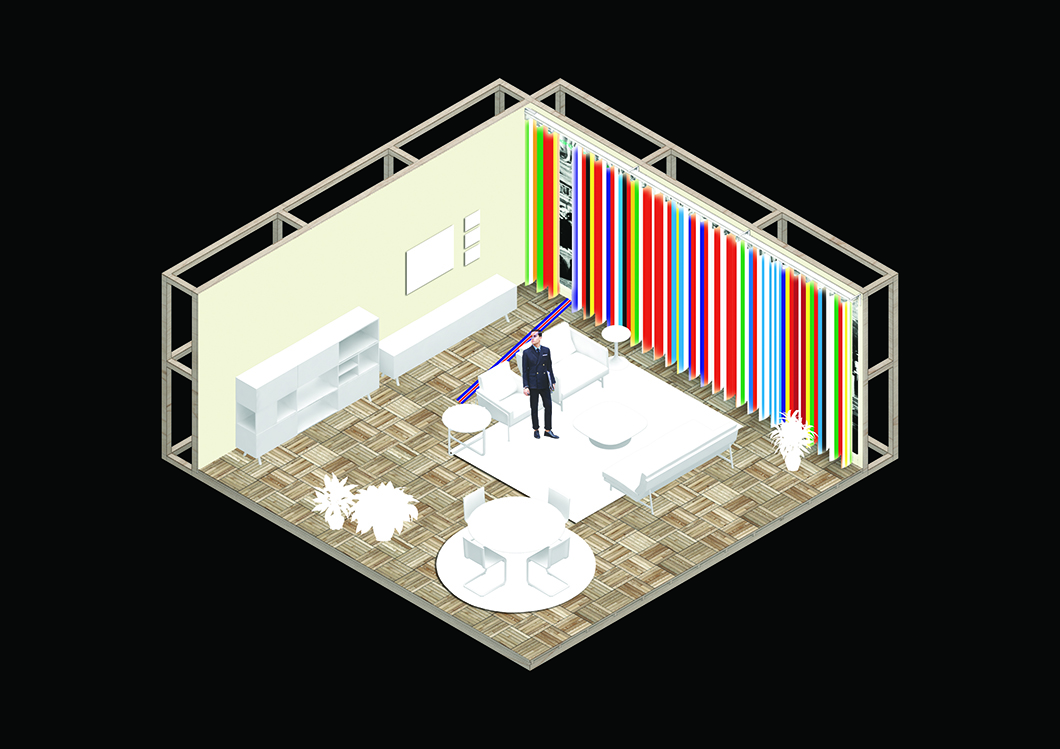

Recently commissioned by the London Design Museum for the inaugural show in its new location, OMA has now designed what appears to be an a innocuous installation of a domestic living room. But the chairs, tables, and blinds that fill the space, all excellent examples of modern design, are there to make a point. They are in situ answers to the title of the exhibition—Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World.

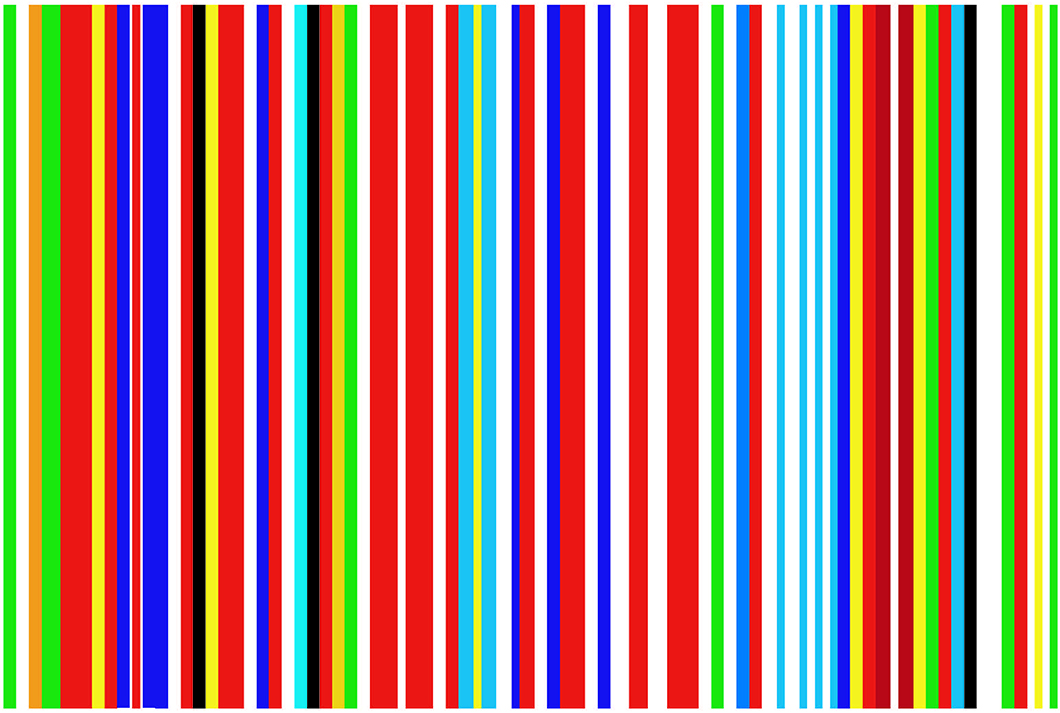

The proposed EU "barcode" designed by OMA in 2001. Image courtesy of OMA.

For OMA, the installation, dubbed the Pan-European Living Room, meant revisiting an old idea. The firm presented a radical proposal for the flag of the European Union in 2001, and while it was never officially adopted, the pinstriped image has persisted in popular consciousness. “We invented the EU barcode some fifteen years ago: an alternative, colourful symbol for the European Union,” the firm explains. “A symbol of optimism. The EU—that was the idea—could be fun.”

Years later, the optimism has waned. But after the shock of Brexit and the resurgence of protectionist sentiments around the world, the firm, led by architect Reinier de Graaf, was prompted to reconsider their vision of a united continent.

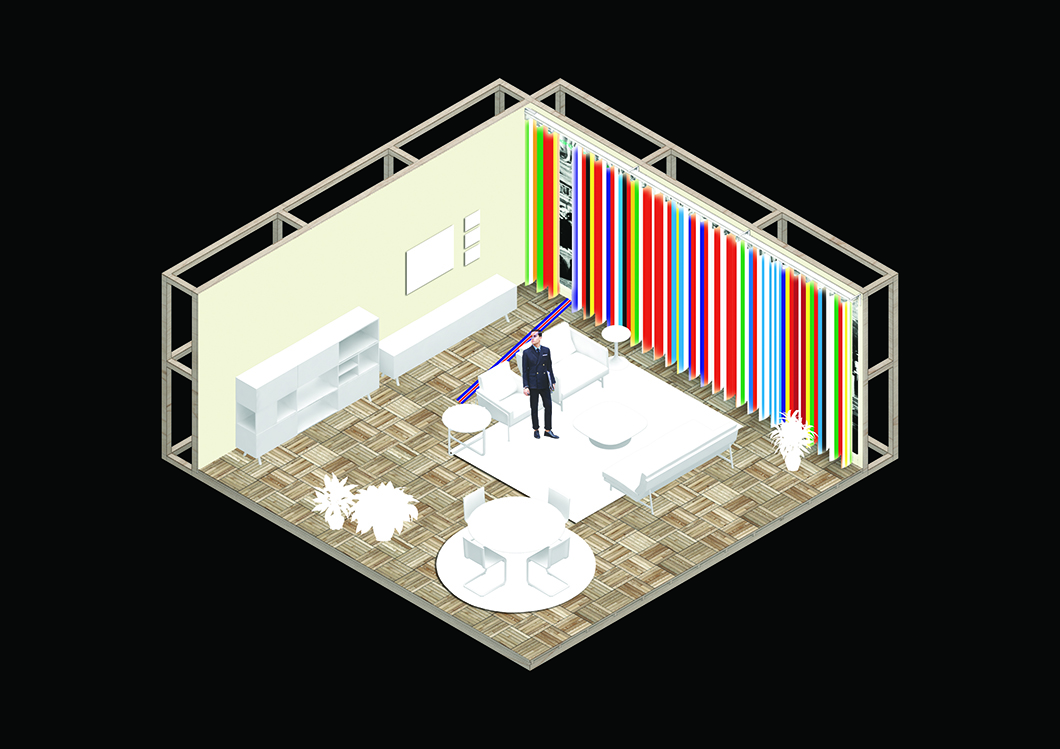

The Pan-European Living Room, backlit by the EU barcode with Britain removed. Photograph by Luke Hayes, Courtesy of the Design Museum.

“The whole issue of the Brexit is specifically connected to fear and love, especially fear. So we took the event as the starting point of our installation,” Bantal told Knoll Inspiration. “And pretty soon, we realized that if Brexit happens, it’s a disaster for our flag. If Britain was out then we would get a hole, one part missing. Then, of course, [the flag] becomes the first part of some big crumbling; you could use it to display the dangers and the background of what Europe used to be.”

The installation began with the backdrop: a sliced up version of the EU barcode mounted on vertical blinds—a staple of the European home and a symbol, according to OMA, of growing desires for privacy and aloofness. “There were a number of metaphors that we thought were quite humorous to use,” said Bantal. “It was almost evident that the blinds and the mechanics behind them should represent the flag. Before we knew it, all these parts of the puzzle began to fall together in a very coherent and clear message.”

The Pan-European Living Room includes furniture by Knoll designers who immigrated to the United States. Photograph by Luke Hayes, Courtesy of the Design Museum.

While the 2001 EU barcode has been transformed into a backlit curtain for the room, the crux of the installation is the collage of furniture that comprises it, arranged in a manner typical of domestic life. The setup presents an allegory of Europe’s collective cultural achievements, starting with objects and an environment that are immediately familiar.

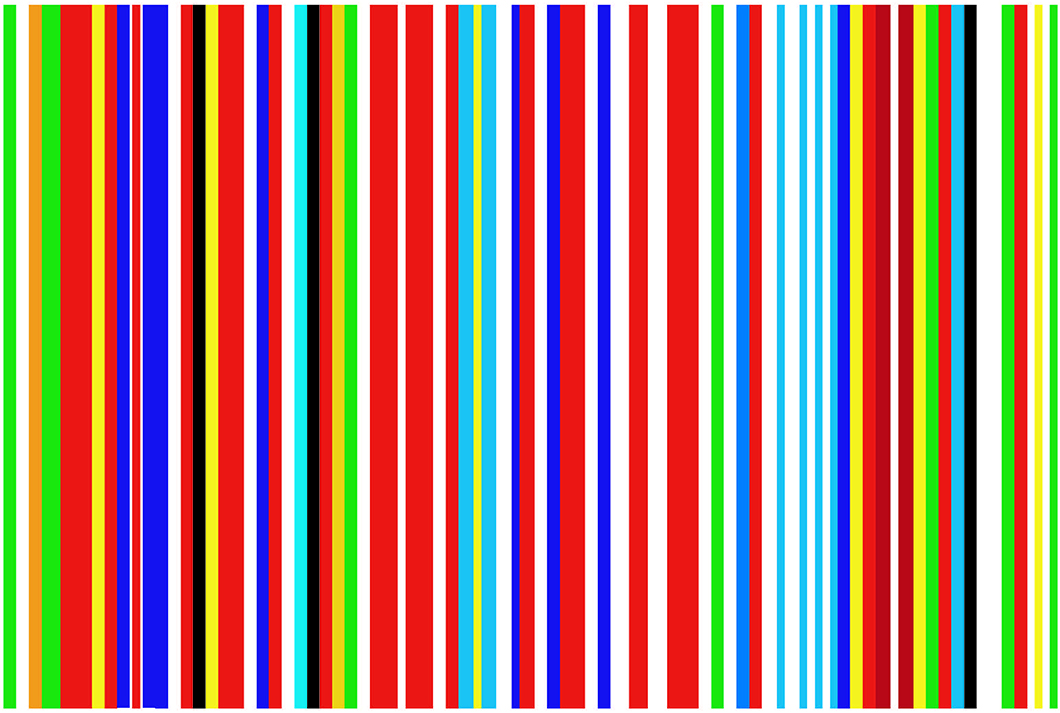

Each piece of furniture was selected for its origins in a different country: a set of Cesca Chairs by Marcel Breuer stand in for Hungary, a Dining Table by Eero Saarinen celebrates the influence of Scandinavian design, while Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Table represents Germany in OMA’s “object catalogue.”

“Our most intimate daily environment constitutes the most eloquent example of Europe’s collaboration.”

—OMA

The object catalog of the exhibition celebrates the diverse origins of modern design in the European context. Image courtesy of OMA.

“The furniture is Europe, emphasizing Europe’s fundamental commitment to modernity,” the designers explain. “Evidence that, despite the UK’s recent political choice, the process of Europe’s cultural integration continues, with or against the odds. Our most intimate daily environment constitutes the most eloquent example of Europe’s collaboration.”

The room, while intentionally arranged, is not a fixed tableau. It is instead a reconfigurable reminder of diversity in design and its endless potential. “Our point was not to specifically say that this chair should be only this chair,” explained Bantal. “The room, in how it is designed, could have a thousand other possibilities because for every combination of furniture you could create a different room. The idea was basically to say, for example, that without a chair or table there is no dining—all these things are connected.”

Axonometric projection of the Pan-European Living Room, an allegory for cross-border collaboration. Image courtesy of OMA.

In placing objects of eclectic origins in close quarters, many of which were made by European designers who immigrated to the United States and subsequently collaborated with Knoll, the Pan-European Living Room argues that the reality of the modern interior is inextricable from cooperation, trade, and continuous cultural exchange.

Bantal offered an example: “If Knoll wants to have a piece of furniture designed, it's often about asking international designers to collaborate,” he said. “You become a diplomat, almost, as a company—moving between different borders and cultures before the final product exists.”

“You become a diplomat, almost, as a company—moving between different borders and cultures before the final product exists.”

—Samir Bantal

From Knoll to the world—a diplomat of design. Image from the Knoll archive.

While trade and protectionism are most often considered in terms of agriculture or economics, the Pan-European Living Room scales the issue down to a register immediately comprehendible, and so perhaps even more ominous. “In a way,” concludes Bantal, “design, without being intentionally political, is always political.”

The exhibition Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World will be on view through April 23, 2017 at the Design Museum in London.